| |

In 1959, I graduated from M.I.T. with bachelor’s and Master’s degrees and immediately went to work at M.I.T.’s Naval

Supersonic Laboratory (NSL) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. After a few years at NSL, some of the staff - myself included - left to form a small

engineering company, MITHRAS, Inc.

In the mid-1960‘s, MITHRAS was purchased by a Bronx, N.Y, company called Loral Electronics Corporation, which in

turn, around the year 1970, was bought up by Sanders Associates, Inc. (SA).

Sanders Associates, Inc. was headquartered in Nahua, New Hampshire. Shortly after being acquired, the MITHRAS operation

was relocated from Cambridge, Massachusetts to Nashua. It was there that I met Ralph Baer.

When I was introduced to Ralph Baer, I was told that he was responsible for some very important and profitable inventions

and was one of the “associates” that formed “Sanders Associates”. I subsequently got better acquainted with Ralph, finding out that he, like, me was

Jewish. Ralph and I were two of the few Jewish engineers working at Sanders at the time.

As the New York Times describes it, "it was a sultry summer day in 1966 when Baer — who was working as an engineer

for defense contractor Sanders Associates, now part of BAE Systems — scribbled out a four-page description for 'game box' that would allow people to

play action, sports and other games on a television set."

One Sanders executive saw potential in Baer's idea and gave him $2,500 and two engineers to work on the project. Over the

years the Baer team churned out seven prototypes in a secret workshop, before settling on a version that Baer and Sanders would use to file the

first video game patent in 1971.[1]

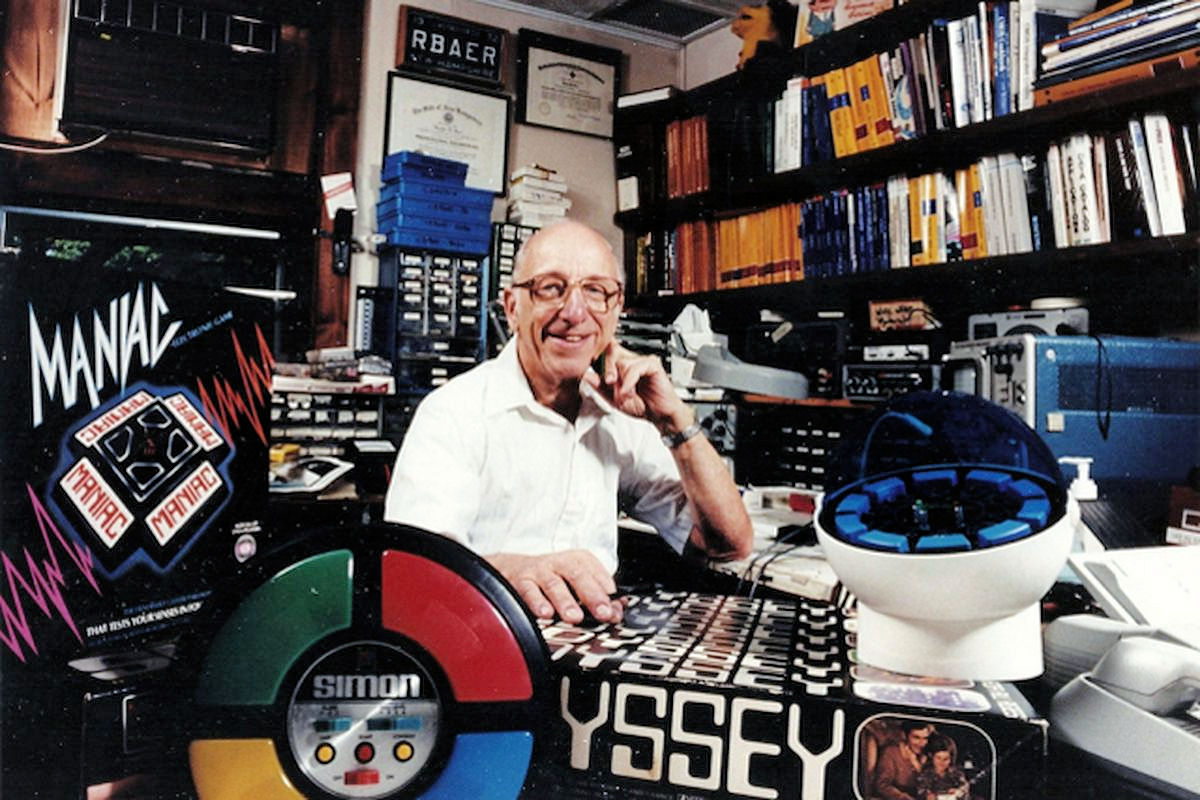

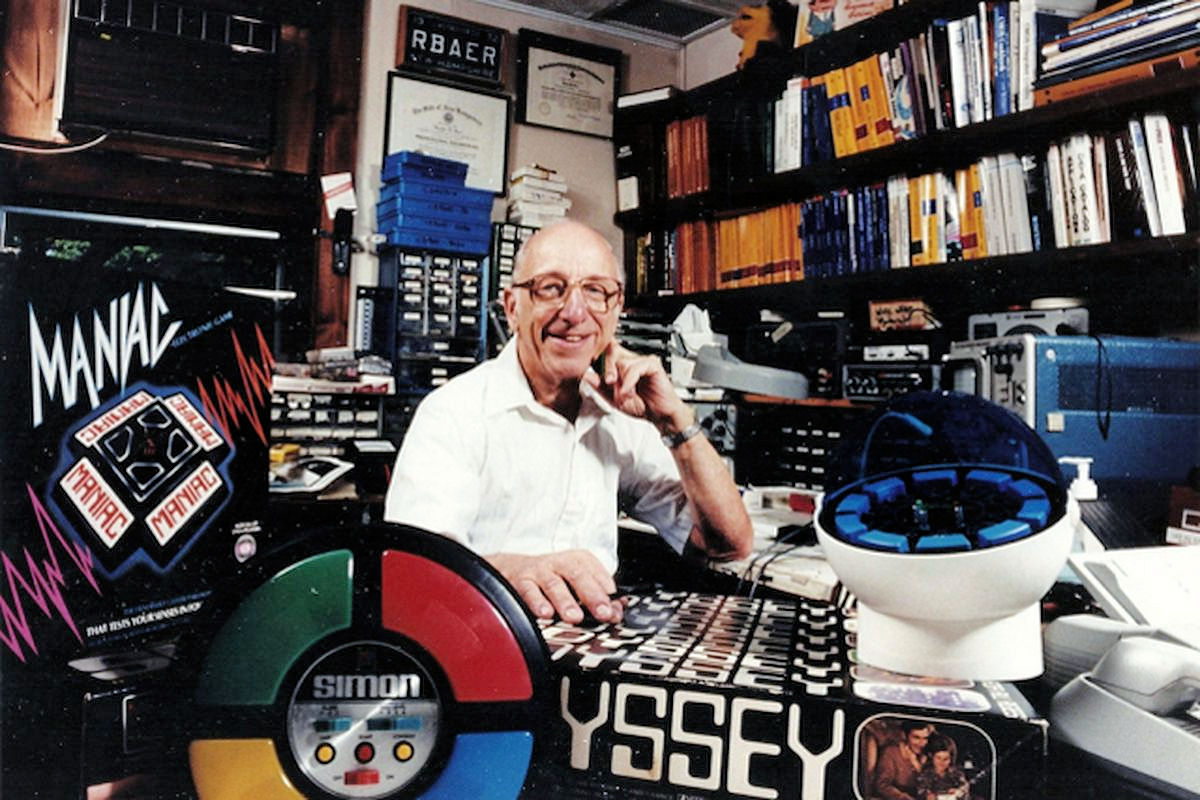

Ralph Henry Baer (1922-2014) was a German-American inventor, game developer, and engineer who is best known as “the Father

of Video Games”. Over the course of his life, his inventions and over 150 U.S. and international patents have contributed to the advancement of

military defense, including tracking systems for submarines, and to television technology, video gaming, electronic toys, and other consumer

electronic products. He forever changed the way humans interacted with machines for purposes of interactive play, not only through his own games

and devices, but also through his incredibly prescient vision of the main evolutionary lines of future video game development.

On February 13, 2006, Baer was awarded the National Medal of Technology by President George W. Bush for “his

groundbreaking and pioneering creation, development and commercialization of interactive video games (which were originally called “TV games”),

which spawned related uses, applications, and mega-industries in both the entertainment and education realms”. He was inducted into the National

Inventors Hall of Fame at a ceremony at the United States Department of Commerce.

Born in Germany to parents, Baer was raised in the Jewish tradition. He continued to strongly identify as a Jew throughout

his life.

In the Germany of his youth, Baer’s father ran a leather tannery business and supplied leather to the town’s major shoe

factories. After being expelled from school at age 14 pursuant to Nazi anti-Jewish laws, Baer’s friends disowned him – including his best friend,

who joined the Hitler Youth movement.

Baer attended a Jewish school and, after his father’s successful business was destroyed by the Nazis and their minions,

he began working in a small office to help support his family, where he quickly learned typing, filing, and bookkeeping. The situation turned

increasingly dire when Ralph’s father was forced out of his tannery business for being a Jew – even though he was a veteran who, while serving

with Germany during World War I, had earned medals and been wounded twice, once on the Western Front and once on the Eastern Front. The Baer

family fled Germany to the Netherlands in 1938 – only two months before Kristallnacht. All of Baer’s paternal uncles and cousins were murdered at

Buchenwald and Treblinka.

In obtaining exit visas for the United States, the family had two important advantages. First, the young Baer had taught

himself a virtually accent-free English, which deeply impressed the immigration authorities and enabled them to more easily obtain visas from the

U.S. consulate. Second, the family was fortunate that their maternal relatives in the United States provided the necessary affidavits and promises

of support for their immigration.

The family settled in the Bronx, N.Y., where Baer changed his name from Rudolph Heinrich to Ralph Henry to avoid the

disgrace of being associated with Nazi Germany and, within a week after his arrival in New York, he was working an 8:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. shift

in a factory that produced leather manicure kits for the Avon cosmetics company.

Six months later, after seeing a subway passenger reading an advertisement for education in the electronics field, he

signed up for a correspondence course at the National Radio Institute in radio and television electronics, spending $1.25 out of his

weekly $12 salary.

In 1943, Baer was drafted into the army and sent to become a combat engineer at Fort Dix, N.J. Two months later, he was

sent to Camp Ritchie in Maryland, which in 1942 had become the army’s first centralized military intelligence training center. With the focus of

the center on training American soldiers who were fluent in German and Italian in intelligence, psychological warfare, and interrogation tactics

and techniques, Baer found himself among other Jews who had fled Germany. As one of the famous “Richie Boys,” he became a recognized

weapons expert, was awarded a medal for his marksmanship, and spent most his time collecting and writing information about different types of

American, German, and Italian weapons. He was sent overseas, initially to Liverpool, England, where he and his squad educated British soldiers

on various intelligence subjects, and then to Paris, France, where he worked on small arms weapons.

Upon his return to New York in 1946 after the war, Baer first began work for Emerson Radio, where he repaired

nonfunctioning radio and television sets but. A short time later, he resigned to take advantage of G.I. Bill tuition benefits. However,

notwithstanding his broad knowledge and indispensable experience, he found it difficult to find a university that would admit him, first because

there were so many veterans pursuing similar plans but, more importantly, because his school records had been left behind in Germany - Hitler had

seen to it that he received little formal education.

But he was admitted to the American Television Institute of Technology (ATIT) in Chicago, where he worked with

influential inventors such as Lee De Forest, who had invented the vacuum tube and discussed his project for a color television (which he would

later patent) with him. At ATIT, Baer went on to earn the first Bachelor of Science degree in television engineering.

As the result of rising federal financial allocations for national defense spending during the Cold War period, and with

research and development and manufacturing firms capitalizing on what has now become well-known as “the military-industrial-complex,” there were

abundant opportunities for engineers like Baer. He went on to work primarily for private military defense companies throughout his career, beginning

in 1949, when he commenced work for a short time building medical machines as an engineer for Wappler Inc., a small New York electro-medical

equipment firm. He quit Wappler for a senior engineer position at the Loral Electronics Corporation, where, as a defense contractor, he

designed power line carrier signaling equipment and various electromechanical equipment, including military systems.

When he was commissioned at Loral to build a luxury, large screen television set with Leo Beiser, who would later pioneer

laser beam information systems, Baer began thinking about what other possible uses televisions might have, and he hit upon the idea of including a

games component in the televisions they were building. He presented his idea to Loral and, in one of the worst decisions in all of corporate history,

the company expressed no interest in the project. He was sent back with instructions to continue working on the luxury television set. When it failed

to sell and he was denied any reasonable raise in pay, he saw no future at Loral and left to take a position as a chief engineer at Transitron

Electronic Corporation in Wakefield, Massachusetts, where he successfully filed for two patents for his development of a transmitter that was

half the weight and size of existing models.

Baer then went to work for Sanders Associates, Inc. (SA) in Nashua, New Hampshire, and moved his family to

Manchester, New Hampshire. Sanders had become broadly recognized as a leader in defense technology with a specialization in complex flexible circuit

assemblies and printed wiring boards. (Sanders was later sold to Lockheed Martin in 1995 and then to BAE Systems in 2000.)

Baer’s primary responsibility at Sanders in the 1950s, was supervising about five hundred engineers in the development of

electronic systems being used for military applications. However, he had never given up on his general idea to transform the passive television

screen into an entertaining platform for interactive games, but Sanders had no consumer electronics division. Nonetheless, he realized that the

significantly lower prices for television sets – and the fact that most American homes were acquiring them – had opened up a huge potential market

for other applications, and he began work in secret on his “game box,” which he called Channel L.P. (for “Let’s Play”).

Baer presented his idea to the Sanders board of directors and, in the first iteration of his design concept in 1966, he

listed several games that he thought he could design for television sets, including action, board, instructional, chance, card, and sports games.

His original schematic design shows the circuit building blocks needed to place two dots on a television that could then be manipulated and moved

around on the screen. Collaborating with an engineering technician at Sanders, he built an experimental unit to test his theoretical model: the

first console to use vacuum tubes instead of the far more expensive and complex early circuit chips of the newly emerging transistor technology.

When he presented the experimental unit to the Corporate Director of Research and Development, he cleverly spun it as a “gaming model,” a term of

art used in military contracting, rather than as merely a toy.

The company green-lighted the project and gave Baer a $2,500 grant and, after sketching out game ideas with other Sanders

engineers, within a year he came up with the original ideas for, among other things, adapting the “joysticks” of the aeronautical industry to his

gaming console and developing technology to enable a user to point a light gun and to shoot at the screen. Of particular historical importance, he

created the famous two-player table tennis game and, perhaps most significantly, he and his collaborators successfully built the “Brown Box”

console video game system, so named because of the wood grain, self-adhesive brown vinyl that covered the console. The Brown Box, which turned

televisions into interactive devices and launched the multi-billion-dollar era of video games, proved so successful that in an early demonstration

and meeting with a patent examiner and his attorney, within minutes every examiner on the floor of the building was in that office wanting to play

the game. The Brown Box was patented on April 17, 1973, given U.S. Patent No. 3728480, and became jointly owned by Ralph Baer and BAE Systems.

Baer’s invention was licensed in 1972 to Magnavox, which released it in September 1972 as the Magnavox Odyssey.

Odyssey initially contained twelve games, including Ping-Pong. As the first video game console for home use, it sold 130,000 units in its first year

on the market, but Baer maintained that because, against his advice, the product was priced too high, Magnavox sold many fewer units than it should

have. He was also unhappy because Magnavox only sold the units in its own retail stores and ran ads that gave the false impression that the units

would only operate in a Magnavox television set. Nonetheless, it sold some 350,000 units by 1974.

Magnavox sued many video game developers for patent infringement and, in a 1976 case against Atari for its tortious

interference with Magnavox’s patent rights by using proprietary technology to design its “Pong” game, the court ruled against Atari based upon two

significant factors. First, because of Baer’s military training and military contracting experience, he kept and maintained meticulous records, which

proved invaluable in court in protecting Magnavox’s claims. Second, the court found that the Magnavox games contained or used a “play-controlled

hitting symbol” invented by Baer pursuant to which players could manipulate symbols that could strike each other within a video game on a television

screen (as, for example, the paddle hitting the ball in table tennis game).

After his dramatic success with the Brown Box, Baer was given bonuses and stock options and was afforded the opportunity to

work on projects of his choosing. In what he characterized as “a piece of Jewish chutzpah,” he took advantage of his new freedom to work with

research and development groups to create advanced display technology and video-based training and simulations using VCR’s, Video-Discs, DC-ROMs

and digital computers, and he applied his video gaming acumen for military use by developing a precision rifle training apparatus for military

training purposes.

In 1975, Baer established his own side consulting firm, R. H. Baer Consultants, through which he partnered with

well-known companies including, for example, Hallmark, for whom he designed the first talking cards, and FTD Flowers, for whom he

developed a recording device that allowed people to record a voice message onto a keepsake to be delivered along with the flowers. He also invented

interactive talking stuffed animals, voice storage and playback devices for interactive children’s books, the electric light gun, a split keyboard

organ, “talking tools” for children, and “Bike Max,” speaking bicycles that played back the bike’s speed, distance traveled, and warnings to prevent

bicycle theft. Although few have ever even heard his name, let alone associated his name with it, Baer’s best-known game is probably the iconic

"Simon" (1978), an electronic game of short-term memory skill that remains popular even today.

On April 8, 2021, the United States Mint announced that the American Innovation $1 Coin representing

New Hampshire would recognize the invention of the first home video game console by Baer. The “heads” design features a dramatic representation

of the Statue of Liberty in profile, and the “tails” design is intended to evoke the symbol of an arcade token: to the right side of the coin is

one of Baer’s Brown Box games, “Handball;” the left side reads “New Hampshire” and “Player 1;” and encircling the outside of the coin is text

intended to pay homage to Baer, “IN HOME VIDEO GAME SYSTEM” and “RALPH BAER.”[2]

Ralph Baer died in Manchester, New Hampshire on December 6, 2014 at the age of 92.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References:

- Inventor Ralph Baer, The 'Father Of Video Games,' Dies At 92, Steve Mullis, npr, 8 December 8 2014.

- Ralph Baer: The Jewish Holocaust Survivor Who Invented The Video Game, Saul Jay Singer, The Jewish Press,

23 August 2024.

|

|