| |

Fifteen years after admitting to the vicious murders of three innocent people and after

being convicted and sentenced to death, a convicted triple murderer still has not been executed and is back in court,

appealing the death sentence because one of the jurors omitted her background as a domestic abuse survivor at

his sentencing trial.

In 2003, a drifter, Gary Sampson, was sentenced to death in Massachusetts for the carjack

killings of two men from that state. Now, thirteen years later, that sentence has still not been carried out and

another jury has been asked to determine if he should be put to death. His guilt or innocence is not in question –

he confessed to the murders.

Sampson pleaded guilty and was sentenced to death in 2004, but a judge granted him a new

trial in 2011 after learning of the female juror’s omission of domestic abuse during juror qualification.

Sampson was a 41-year-old career criminal when he went on a weeklong rampage in July 2001.

He left North Carolina, where he was a suspect in a string of bank robberies, and returned to Massachusetts where

he grew up.

His first victim was a 69-year-old retired pipefitter who picked Sampson up hitchhiking.

Sampson tied McCloskey up and stabbed him 24 times. He then killed a 19-year-old college student who also gave

Sampson a ride. Sampson tied this victim to a tree, stabbed him repeatedly and left him to die in the woods.

Sampson continued his killing spree in New Hampshire, where he strangled a former Concord

city councilor. For this murder, Sampson was sentenced separately in New Hampshire to a life term.

Massachusetts abolished the death penalty in 1984, but Sampson, now 57, was prosecuted

under federal law, which allows prosecutors to seek the death penalty when a murder is committed during a

carjacking.[1]

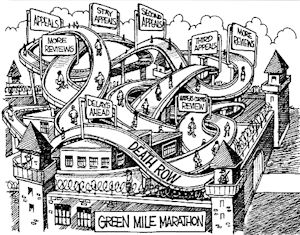

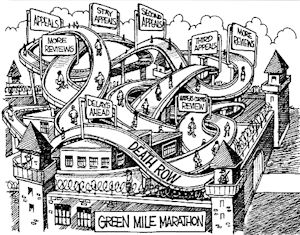

“Even if the new jury sentences him to death, {Sampson} will still have a years-long

appeals process ahead of him.

“Seventy-five people have been sentenced to death on federal charges in the U.S.

since 1988, but only three of them have actually been killed. . . [Emphasis mine] (Ref.

2)

In 2015, a jury sentenced Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev to death for his

involvement in the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing that resulted in four deaths and, more than 200 injuries, several

of which required limb amputation. The death sentence has not been carried out as the lengthy appeals process

proceeds at snail’s pace through the court system. Here again, guilt or innocence is not the issue.

[2]

Whatever happened to the biblical injunction of “An Eye for an Eye”?

From the Old Testament, we read: “If a man injures his neighbor, just as he has done, so

it shall be done to him: fracture for fracture, eye for eye, tooth for tooth; just as he has injured a man, so it

shall be inflicted on him. Thus the one who kills an animal shall make it good, but the one who kills a

man shall be put to death” --- Leviticus 24:19-21 and "Thus you shall not show pity:

life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot.” ----

Deuteronomy 19:21

In a similar vein, where has the demand for timely trial and sentencing gone?

William E. Gladstone, the British Statesman and Prime Minister (1868-1894), and the most

prominent man in politics of his time, (1809-1898) was quoted as saying, “Justice delayed is justice denied.”

The phrase means that if legal redress is available for a party that has suffered some injury, but is not

forthcoming in a timely fashion, it is effectively the same as having no redress at all. This principle is

the basis for the right to a speedy trial and similar rights which are meant to expedite the legal system,

because it is unfair for the injured party to have to sustain the injury with little hope for resolution.

The phrase has become a rallying cry for legal reformers who view courts or governments as acting too slowly

in resolving legal issues because the existing system is too complex, overburdened, or simply unjust. While the

phrase is normally applied in the case of someone accused of a crime, it should as well be applied to the victim

of a crime or the families of crime victims when the victim is unable to call for justice on his/her own

behalf.

Also, “Mentions of justice delayed and denied are found in the Pirkei Avot 5:7, a section

of the Mishnah (1st century BCE – 2nd century CE): "Our Rabbis taught: ...The sword comes into the world, because

of justice delayed and justice denied...",[3] and the Magna Carta of 1215, clause 40 of which reads, ‘To no one

will we sell, to no one will we refuse or delay, right or justice.’ “ (Ref. 3)

''For every prisoner stalling execution with interminable appeals, there's a family member

who has spent all those years of appeals waiting for justice to be done.'' . . . ''We owe these families something.

We owe the victims something.'' (Ref. 4))

“Death-sentence appeals take too long, traumatize victims' families and burden states with

millions in extra costs for housing convicted killers, a draft of a new study commissioned by the Justice Department

shows.

“The study also found that death penalty cases are not hopelessly flawed by errors, as

opponents of capital punishment have charged.

“The study, which reviewed state death sentences issued in the 1990s, found that 26% were

reversed during the first level of the appeals process. Most of those ‘direct appeals’ were rejected because of

sentencing errors. Some of the death sentences were later reinstated.

In only 11% of those cases did the appeals court find problems with the underlying murder

convictions . . .

- - -

" ‘Opponents of the death penalty can't get an outright repeal anywhere, but are working to

impede the process by slowing it down to a crawl,’ . . .” (Ref. 5)

)

“. . . {C}ondemned prisoners in America typically spend a very long time waiting to die. The

appeals process can drag on for decades. . . . For prisoners who are actually put to death, the average time

that elapses between sentence and execution has risen from six years in the mid-1980s to 16.5 years now. And even

that startling figure makes the process sound quicker than it is, because most condemned prisoners will never be put

to death. . . .

“At the end of 2011, there were 3,082 prisoners on state and federal death rows in America.

That year, 43 were executed. At the current rate (which is slowing) a condemned prisoner has a one-in-72 chance of

being executed each year. Because the average death row inmate was 28 when first convicted, it seems unlikely that

more than a fraction of them will ever meet the executioner. In 2011, 24 condemned prisoners died of natural causes

and 70 had their sentences commuted or overturned. (There were 80 fresh death sentences passed in 2011, so the number

of people on death row shrank by 57.)

“The number of death-row inmates who die of old age can only be expected to increase. The

death penalty was restored only in 1976, so nearly everyone on death row was convicted after that date, and most were

young when convicted. As they get older, more will start to die each year of heart attacks, strokes and cancer.

. . . (Ref. 6)

Swift and impartial justice should be afforded the accused. But swift and impartial justice

is also due the victim and the victim’s family. Society as a whole also deserves the assurance that justice will be

fair, sure and timely. Fifteen or more years on death row for an admitted and convicted killer is neither fair nor

swift.

While these vicious murderers go through our convoluted justice system, you and I pay the

bill for prosecuting them (and probably the bill for defending them), housing them until execution, and paying for

their interminable appeals process (for both the appeal and the opposition to the appeal).

Based upon one analysis conducted in 2011, I came up with an estimated cost of $1.85

million to try, house and go through the appeals process, broken down as follows:

Trial and Appeals - $1.10 million: Trial Attorneys - $500,000; Court Costs - $85,000;

Appeals - $115,00; Petitions - $400,000.

Prison - $0.75 million: 15 years in prison at an annual cost of $50,000 per year =

$750,000.[7]

Assuming about 3,000 death row inmates[8]

in the United States and 100 death sentences a year, we are paying about $260 milion annually for the convictions,

appeals, and upkeep of these murderers.

In California, the family of a murder victim, their daughter, recalled the injustice of the

criminal justice system with regard to their daughter’s murderer. Their daughter’s murder was just “the first

trauma the {family} faced. The second was the ‘horrible’ trial, in which the family was not even allowed into the

courtroom. ‘After going through the criminal justice system I soon found out that the justice system is not for the

victims,’ {the mother said}. ‘It’s for the perpetrator.’

- - -

“The answer {to this problem} is reform . . . ‘Reform the appeal process, reform death row

housing and victim restitution, reform the appointment of appellate counsel and the agency that overlooks it—those

are the key things—‘ . . .

“. . . The {reform} plan {proposed} would also limit the appeals process to five years,

transfer challenges to lower courts and require prisoners to work and pay restitution to their victims.

“ ‘We want the cases reviewed in a timely manner,’ . . . ‘In the typical case, it is

entirely feasible for all state court reviews to be completed in five years, as opposed to 10 or 15 now. It will

save money by shortening the amount of time prisoners are kept on death row.’ “

(Ref. 9) Capital punishment cases can be sped by designating trial courts to hear

petitions challenging death row convictions, limiting successive petitions and expanding the pool of lawyers who

could take on death penalty appeals.

What we need is a major overhaul of our American justice system dealing with capital

punishment. Since most death sentences are now federally imposed and nearly all death sentences end up being

appealed to the United States Supreme Court, let’s impose a nationally standard and uniform set or rules governing

capital punishment. Let’s start with ensuring that death sentences are only applied to situations where there is

essentially certainty that the accused committed the murder(s) and that the killings were vicious enough to

warrant the death penalty. Next, let’s set a firm and practical time limit for the appeals process - say 3 years –

so that the time from initial indictment to imposition of the death penalty does not exceed a reasonable span

of time – say 5 years. Let’s have no more 15, 20 or 25 years on death row for brutal killers. Let’s put our courts

and lawyers to more useful pursuits.

Vicious killers deserve to be executed – an eye for an eye. These murderers are entitled to

a fair and expeditious trial. If convicted, they are entitled to a swift appeals process.

Once convicted and their sentences appealed, their victims and their victims’ families are entitled to quick and

appropriate implementation of their sentences – justice delayed is justice denied.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References:

- Testimony To Begin In Gary Sampson Death Penalty Sentencing Retrial, DeniseLavoie,

CBS Boston, 2 November 2016.

- Massachusetts murderer Gary Lee Sampson's death penalty trial begins today, Phil Demers,

MASS LIVE,

1 November 2016.

- Justice delayed is justice denied, Wikipedia, Accessed 2 November 2016.

- Whitman Forms Panel to Expedite Death Penalty Cases, Jennifer Preston, New York Times,

7 August 1997.

- Study draft decries execution appeals process, Richard Willing, USA Today,

1 March 2007.

- Why so many death row inmates in America will die of old age, Gary Alvord, The

Economist, 3 February 2014.

- What costs more the death penalty or life in prison?, NBC Right Now,

22 September 2011.

- DEATH ROW INMATES BY STATE, DEATH PENALTY INFORMATION CENTER, 1 July 2016.

- Death Penalty Debate: End Executions or Expedite Process?, Caitlin Yoshiko Kandil,

sanjoseinside, 16 April 2014.

|

|