| |

Late in January 2023, an obituary appeared in the New York Times. It announced that,

George Zimbel, Photographer of Marilyn Monroe and J.F.K., Dies at 93[1]

George Zimbel was one of three people named George who were part of my early life. To me,

George Zimbel was always referred to as “Little George”. He was a first cousin of mine. Another relative of mine,

who was also named George was my “Uncle George”. His last name was spelled “Zimble”, as were all the other members

of the Zimbel/Zimble clan – except for Little George’s immediate family. The third George in my life was

Captain George. He was not initially related, but posthumously became my sister’s bother-in-law in 1948 when

she married Captain George’s younger brother.

Little George died on 9 January 2023 in a care facility in Montreal, Canada at the age of

93.

As reported in the obituary, George Zimbel was a genial photographer who had empathy for ordinary

people, but whose two best-known subjects were megastars, Marilyn Monroe and John F. Kennedy.

He captured people in the act of living: A sailor reading in his lower bunk on a submarine; a small

boy dwarfed by a Great Dane in Harlem; a little girl playing hopscotch in the street; a baby pulling on a doctor’s

stethoscope; a boy pointing a toy gun at a friend; musicians and exotic dancers in New Orleans nightclubs.

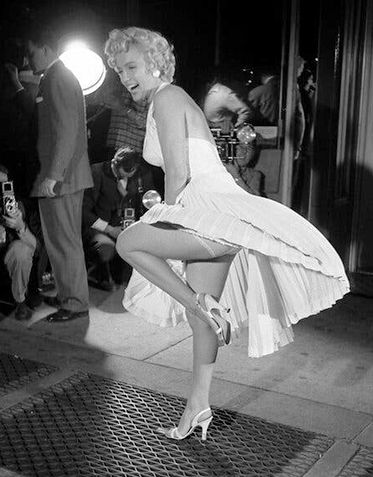

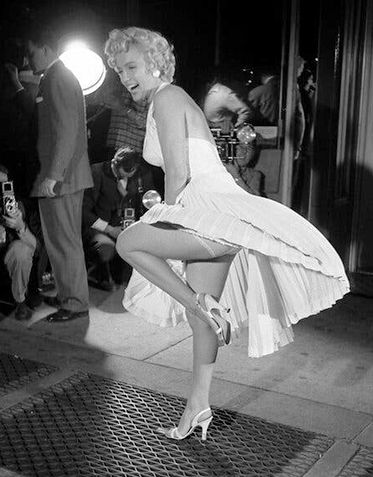

In 1954, Little George photographed a famous scene on Lexington Avenue and 52nd Street in

Manhattan, during the filming of a scene for Billy Wilder’s “The Seven Year Itch” that was also a press event.

Working for the Pix photo agency but without an assignment, he took pictures while a fan beneath a subway grating blew

Monroe’s white dress upward to reveal her underwear, creating one of her most archetypal images.

“This was the greatest publicity stunt ever created,” Little George said in “The Night

I Shot Marilyn” (2016), a short documentary directed by his son Matt and Jean François Gratton. “Still photographers were

just eating it up.”

Little George tucked his negatives away and did not publish the pictures in the aftermath of

the filming. “I’m not sure why,” he said, “but I didn’t.” He moved on to another assignment and didn’t look at the negatives

for 22 years. Eventually he began to sell the images, which were included in various exhibitions and in his book

“Momento” (2015).

Some six years later, Little George photographed John F. Kennedy, then a senator from

Massachusetts, and his wife, Jacqueline, as they greeted the crowd from an open convertible during a ticker-tape parade in

Manhattan late in the 1960 presidential campaign. One of the pictures, taken from behind the Kennedys, made a lasting

impression on Little George.

“The more you look at that picture, the more it gives you the willies,” he said in the film

“Zimbelism: George S. Zimbel’s 70 Years of Photography” (2015), also directed by Matt Zimbel and Mr. Gratton.

“You could never do that picture again. You could never get that close.”

George Sydney Zimbel aka, Little George, was born on July 15, 1929, in Woburn,

Massachusetts, near Boston. His father, Morris, owned a small department store; his mother, Tillie (Gruzen) Zimbel, was a

homemaker and also worked in the store. The Zimbel family lived in an apartment above the store.

Fascinated by the photographs he found in Life and Look magazines,

Little George got a Speed Graphic camera at 14 and became a photographer for his high school and college

newspapers.

Little George began selling photos while still a student at Columbia University.

He also took a class at the Photo League, the left-leaning collective that would shut down in 1951 amid accusations

that it was a Communist front. He learned printmaking, which he would master, and how to be a documentary photographer, which

is how he defined himself for the next 70 years.

After graduating from Columbia with a bachelor’s degree in 1951, Little George studied at

the New School for Social Research under the photographer Alexey Brodovitch, who was art director of the fashion

magazine Harper’s Bazaar.

After two years in the Army in Europe during the Korean War, Mr. Zimbel began his long freelance

career. His photographs appeared in publications including The Times, Look, Redbook,

Architectural Digest and Saturday Review. And for a decade ending in 1964, he indulged in a personal

project that suited his interest in politics: taking photos of Harry S. Truman, the former president, whenever he was in

New York City, and once at his presidential library and museum in Independence, Missouri.

In the late 1960s, Little George moved into corporate photography and educational work for

a research organization established by the Ford Foundation. He moved to Canada in 1971 as a protest against the Vietnam

War.

There, he and his wife, Elaine, raised two sons, Andrew and Matt, and a daughter, Jodi.

Little George’s work has been exhibited in the United States, Canada, Japan, France and

Spain. He had three shows at the Stephen Bulger Gallery in Toronto. Mr. Bulger, the owner of the gallery, said that Mr.

Zimbel’s pictures showed a basic optimism. “Other photographers in the 1950s had a suspicious view,” he said in a phone

interview. “But George loved to show the best in a situation, which is what he was like as a

person.”[1]

When talking about my cousin George, I usually called him Little George because he was not

very tall. As a young boy, I can remember visiting Little George and his family in Woburn during the 1940s. I and my

family lived in Chelsea, only about 20 miles away, but, to me at the time, Woburn seemed to be in a different world. Sometimes,

we would drive by car and at other times, we would go by public transportation to North Station in Boston and from there

take a train to Woburn.

Little George’s father, Uncle Morris, was relatively uneducated – he had never had a chance

to attend college. But Uncle Morris seemed to know something about everything. As I grew up, I enjoyed the opportunities to

talk with him and get his insights into various topics.

After Little George moved up to Canada, I managed to keep up on the news about him and his

family via his brother and sisters who, like me, remained in the greater Boston area.

During the summer of 1944 an ordinary war-time flight took place. It was an “Administrative” mission.

A B-25 “Mitchell” bomber, nicknamed “El Aguila” (“The Eagle”) was ordered to make a cross-country flight, from Nadzab, on the

island of New Guinea, to Owi Island, off the north-east coast of New Guinea. Weather forecasts included some light rain, but

no major problems were foreseen. On board the plane were four crewmembers and seven passengers.

The bomber left the field at Nadzab on August 30, 1944, as scheduled, but did not reach Owi Island.

It wasn’t until years later that the downed aircraft was found in a mangrove swamp in West Papua. The remains of the eleven

on board were sent home in 1950.

One of the seven passengers on the “El Aguila” was Captain George Shatzman from Chelsea,

Massachusetts.

During the war, downed fliers lost in the Pacific area were often kept in a “Missing in Action”

status for a long period of time after they were lost. Since the Japanese did not keep good records for whom they had

captured, the possibility always existed that, at the end of the War, missing personnel would turn out to have been POW’s all

along. But this was not the case for these men. [2]

It wasn’t until 1950 that the Shatzman family received the final news from the government about

Captain George. The wreckage of the B-25 was found and his remains were identified by a metal belt buckle with his

name engraved upon it. His remains were brought home and he was buried in the Shatzman family cemetery plot at the Liberty

Progressive Cemetery in nearby Everett Massachusetts.[3] The City of Chelsea, where

Captain George was born and raised, named a street corner one block from the Shatzman home in his memory. To this

day, a sign bearing his name stands there.

I was born and lived for a few years in a house right across the street from the Shatzman home. My

older sister married Captain George’s younger brother and is buried in the Shatzman family plot. So, on my annual

visits to my family’s graves in Everett, I also visit the final resting place of Captain George.

One of my mother’s brothers was Uncle George Zimble. He was born on 18 November in 1900

and died in November of 1983. He lived his entire life in Chelsea,

Massachusetts. [4]

As I grew up in Chelsea, and even afterward, I frequently visited with Uncle George. He

always had a smile on his face and a positive attitude toward everything and everyone. This, in spite of the fact that, as a

boy, he had lost a leg. He had a prosthetic leg, a limp, and never used crutches or a cane. In spite of his impairment,

Uncle George always held down a job and frequently worked two jobs at a time. For much of his life, he mainly worked

in the local shoe making industry.

Unlike too many of today’s generation, Uncle George didn’t expect nor ask for any handouts.

He was a firm believer in working for and earning whatever he and his family needed. This Uncle George was a real

rugged individual who worked for whatever he needed, was happy to be able to do so, and never complained about the unfairnesses

of life.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References:

- George Zimbel, Photographer of Marilyn Monroe and J.F.K., Dies at 93, Richard Sandomir, The New York Times, 27 January 2023.

- LOST B-25 “El Aguila” (“The Eagle”) With Crew and Passengers, Bill Beigel, https://www.ww2research.co, Accessed 30 January 2023.

- Capt George Shatzman, findagrave.com, Accessed 2 February2023.

- George Zimble, https://www.myheritage.com/, Accessed 3 February2023.

|

|