| |

Around sixty years ago, I went on a roughly 500-mile “march” from Boston, Massachusetts to

Washington, D.C. That “march” became known as the The March on Washington.

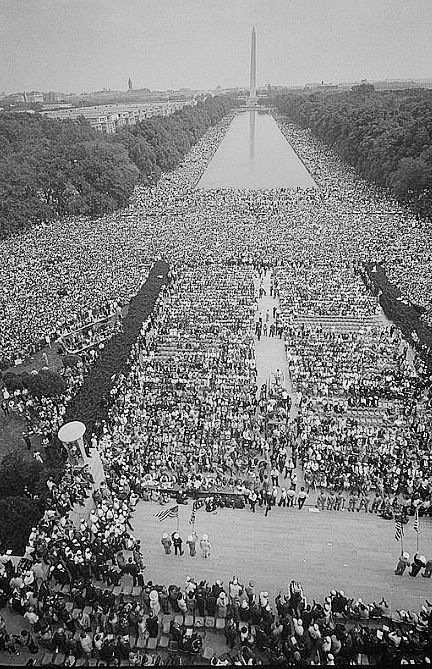

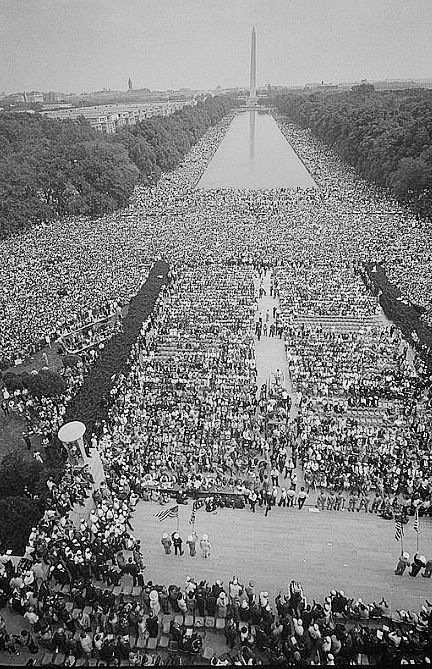

The 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was one of the most significant

protests in American history, bringing more than 250,000 marchers from across the nation to state an unforgettable claim for

racial and economic equality. With its written-in-lightning keystone moment - Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream”

speech - it helped galvanize a generation to fight for an end to nearly a century of Jim Crow segregation.

The march took place on Wednesday, 28 August 1963, a little more than two months after NAACP leader

Medgar Evers was assassinated in Mississippi and three months before President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Texas.

After years of racist violence across the country, it brought together a multi-racial coalition of races, faiths and

professions that, by its sheer weight and cross-section of society, made it the most significant protest for social justice

in the nation’s history.

More than a thousand groups chartered buses. Nearly two dozen special trains brought protesters.

People hitchhiked. The civil rights era leadership - King, A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, Bayard Rustin, Rosa Parks and

John Lewis helped plan the day. The list of celebrities was endless. Sidney Poitier, Lena Horne, Paul Newman, Josephine Baker,

Marlon Brando, Harry Belafonte, Jackie Robinson and Charlton Heston were only a few of the well-known names who

attended.

The Kennedy administration, though supportive of the civil rights cause, was unnerved by the prospect

of so many Black protesters coming to the city. Violence was widely expected by the city and federal government. Thousands of

National Guard troops were brought in to assist police in case of rioting - there was none. Several flights

that day were canceled because of bomb threats. The speech of a young John Lewis was toned down for being too inflammatory.

Author James Baldwin was barred from speaking entirely for the same concerns.

The day began with a group of organizers meeting with members of Congress to officially present these

demands. It ended with King, Randolph, Lewis, and other leaders meeting with President Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon B.

Johnson at the White House. In between was the march and the speeches at the Lincoln Memorial that are now so much part of

the national memory. The march itself was from the Washington Monument west primarily along Constitution Avenue to the

Lincoln Memorial. There, Mahalia Jackson and Marian Anderson sang gospel hymns. Joan Baez and Bob Dylan sang protest songs.

Speeches flowed. The day was sunny, with the temperatures in the low 80s - not bad for Washington in August - but the vast

crowds made it feel much hotter.

Despite the worries of government officials about violence, only three arrests were made on the

day.

August 28, 1963 was an emotional day for a turbulent decade ahead. Less than three weeks later, the

Ku Klux Klan bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, killing four schoolgirls. Kennedy would not survive the

year; King, Malcolm X, Robert Kennedy and many civil rights workers would not survive the decade.

Still, sixty years later, as new protests for some of the same issues fill the nation’s streets, it

is difficult to imagine the nation’s history without the March on Washington.[1]

At the time of The March on Washington, I was working at a small engineering company in

Cambridge, Massachusetts that was a spin-off from a Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) laboratory. Also working with

me was Earl G. Both of us had previously worked at the MIT laboratory and left at the same time when the new engineering

company was formed.

Earl was the same age as I. He was born in Sterling, Ill., moved to Edinburgh, Texas when he was ten

years old and grew up in that deep southern state.

He received a bachelor's degree in aeronautical engineering from the University of Texas and a

master's in that discipline from MIT in 1961. His professional career began in 1958 when he became a research engineer with

MIT's Naval Supersonic Laboratory. From 1967 through 1991, he held various positions at the Air Force Geophysics Laboratory

at Hanscom Air Force Base in Massachusetts.

Later, Earl received a doctorate in Astro geophysics from the University of Colorado. Earl

became the first director of the Directed Energy Directorate at Kirtland Air Force Laboratory in New Mexico. He helped

reorganize the laboratory and established the Directed Energy and the Space Vehicles Directorates that became part of the

Air Force Research Laboratory, which was created in 1997. Earl served in that position until

2003.[2]

One day, in mid-August of 1963, Earl asked me if I would be interested in taking part in a civil

rights "march" to Washington, D.C. At that time, I had not been much interested in the civil rights movement of the early

1960’s and I had had not paid much attention to the upcoming March on Washington. Being 26 years old and single at

the time, the “march” sounded somewhat interesting, I agreed to join Earl in the event.

Late in the afternoon on Tuesday, 27 August, Earl and I left from our work in Cambridge and drove

across the Charles River to the South End in Boston. There, we joined other participants on the “march” in boarding

a chartered bus. From Boston, we drove through the night until, on the next morning just after sunrise, we arrived at a Black

church in the Baltimore, Maryland area. There, we got off the bus for breakfast at the church. After breakfast, we resumed

our drive to the mass protest site in Washington.

In Washington, we walked or “marched” the short distance from where our bus was parked to our protest

location which was mid-way between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial alongside the Reflecting Pool.

A very strange event occurred during my wandering along the Reflecting Pool. I looked up and there

in front of me was Freddie W. Freddie and I had both grown up in Chelsea, Massachusetts, eventually just one street apart.

Until college, we had gone to the same schools, played basketball together and hung around with the same friends. We had not

seen each other in more than half a dozen years. Then, among a crowd of 250,000 or more people from all over the United

States, 500 miles distant from our home city of Chelsea, we ran into each other.

After the speeches were concluded, Earl and I walked back to the bus that would return us to Boston.

We drove through the rest of the day, reaching Boston early evening that Wednesday. We drove back to Cambridge where I got in

my car and drove back home to Chelsea. At that time, I had no idea that I had been part of such a momentous event.

Prior to the March on Washington, I had not gotten involved with the civil rights movement.

Afterward, I took considerably more interest, got involved, and became a member of the NAACP (National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People). Now, some 60 years after

the historic March on Washington, I can’t recall the speakers, the speeches or any of the other accompanying

events that occurred there.

The March on Washington turned out to be a massive protest march. Some 250,000 people

gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial, marking the event that drew attention to the continuing challenges and

inequalities faced by African Americans a century after emancipation. It was also the occasion of Martin Luther King Jr.’s

now-iconic “I Have a Dream” speech.

The following is a brief summary of the events that led up to the 1963 March on

Washington.

In 1941, A. Philip Randolph, head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and an elder statesman

of the civil rights movement, had planned a mass march on Washington to protest Black exclusion from

defense jobs and New Deal programs.

But a day before the event, President Franklin D. Roosevelt met with Randolph and agreed to issue an

executive order forbidding discrimination against workers in defense industries and government and establishing the Fair

Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) to investigate charges of racial discrimination. In return, Randolph called off the

planned march.

Later in the 1940's, Congress cut off funding to the FEPC, and it dissolved in 1946; it would be

another 20 years before the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) was formed to take on some of the same

issues.

Meanwhile, with the rise of the charismatic young civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. in the

mid-1950s, Randolph proposed another mass march on Washington in 1957, hoping to capitalize on King’s appeal and harness the

organizing power of the NAACP.

In May 1957, nearly 25,000 demonstrators gathered at the Lincoln Memorial to commemorate the third

anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education ruling, and urge the federal government to follow through on its decision in the

trial.

In 1963, in the wake of violent attacks on civil rights demonstrators in Birmingham, Alabama,

momentum built for another mass protest on the nation’s capital.

With Randolph planning a march for jobs, and King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference

(SCLC) planning one for freedom, the two groups decided to merge their efforts into one mass protest.

That spring, Randolph and his chief aide, Bayard Rustin, planned a march that would call for fair

treatment and equal opportunity for Black Americans, as well as advocate for passage of the Civil Rights Act (then stalled

in Congress).

President John F. Kennedy met with civil rights leaders before the march, voicing his fears that the

event would end in violence. In the meeting on June 22, Kennedy told the organizers that the march was perhaps “ill-timed,”

as “We want success in the Congress, not just a big show at the Capitol.”

But Randolph, King and the other leaders insisted the march should go forward, with King telling the

president: “Frankly, I have never engaged in any direct-action movement which did not seem ill-timed.”

JFK ended up reluctantly endorsing the The March on Washington, but tasked his brother and

attorney general, Robert F. Kennedy, with coordinating with the organizers to ensure all security precautions were taken. In

addition, the civil rights leaders decided to end the march at the Lincoln Memorial instead of at the Capitol, so as not to

make members of Congress feel as if they were under siege.

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom brought an estimated 250,000 people to the

nation's capitol to protest racial discrimination and show support for civil rights legislation that was pending in

Congress.

Fittingly, Randolph led off the day’s diverse array of speakers, closing his speech with the promise

that “We here today are only the first wave. When we leave, it will be to carry the civil rights revolution home with us into

every nook and cranny of the land, and we shall return again and again to Washington in ever growing numbers until total

freedom is ours.”

Other speakers followed, including Rustin, NAACP president Roy Wilkins, John Lewis of the Student

Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), civil rights veteran Daisy Lee Bates and actors Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee. The

march also featured musical performances from the likes of Marian Anderson, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan and Mahalia Jackson.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. agreed to speak last, as all the other presenters wanted to speak

earlier, figuring news crews would head out by mid-afternoon. Though his speech was scheduled to be four minutes long, he

ended up speaking for 16 minutes, in what would become one of the most famous orations of the civil rights movement - and

of human history.

Though it has become known as the “I Have a Dream” speech, the famous line wasn’t actually part of

King’s planned remarks that day. After leading into King’s speech with the classic spiritual “I’ve Been ‘Buked, and I’ve Been

Scorned,” gospel star Mahalia Jackson stood behind the civil rights leader on the podium.

At one point during his speech, she called out to him, “Tell ‘em about the dream, Martin, tell ‘em

about the dream!” referring to a familiar theme he had referenced in earlier speeches.

Departing from his prepared notes, King then launched into the most famous part of his speech that

day: “And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream.” From there, he built to his

dramatic ending, in which he announced the tolling of the bells of freedom from one end of the country to the other.

“And when this happens…we will be able to speed up that day when all God’s children, Black men and

white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro

spiritual, ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at

last!’”.[3]

The Boston group that went on the March on Washington was one of the largest contingents

to take part. Some 4,000 Bay Staters made the trip that included local leaders. In 1963, Ken Guscott was president of the

Boston branch of the NAACP, the group that arranged to get people from this area to Washington, D.C.

"Our phones were ringing off the hook," Guscott recalled. "People wanted to come from Vermont,

from Maine and everywhere. And it just swelled up, and then we couldn't rent any more buses. We couldn't get any more

buses, so some people went down on the train."

The group left from the South End after a rally attended by Gov. Endicott Peabody.

"We were charging people $26, and those who couldn't afford it, we took them anyway," Guscott

continued. "The thing about it was the governor's wife got so excited; she jumped on the first bus with Mrs. Cass, my

mother and them, and went to Washington with us. She jumped on the bus and went down there with us — that showed you

what an integrated group we had."[4]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References:

- Protests That Changed America: The March on Washington, Neely Tucker, Library of Congress,

10 June 2020.

- AFRL Directed Energy Directorate’s first director dies, Jeanne Dailey, kirtland.af.mil,

6 January 2015.

- March on Washington, history.com, 10 January 2023.

- Boston Voices Remember The March On Washington, Delores Handy, wbur.org,

27 August 2013.

|

|