| |

Over the past 20-years, I have become an unrepentant opponent of guns in America.

[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10) I have reached this status as a result of the innumerable gun deaths,

injuries caused by guns, mass shootings, and violent crimes committed with guns in these united States of America.

My 21-year old grandson has now achieved maturity and, along the way, has become an ardent gun advocate, supporter of the Second Amendment, and a fierce advocate of every American’s “right to bear arms”.

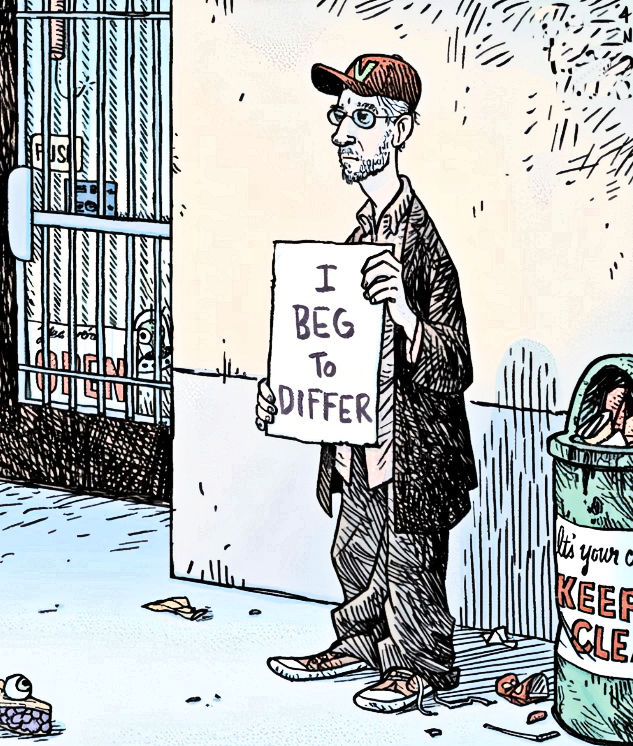

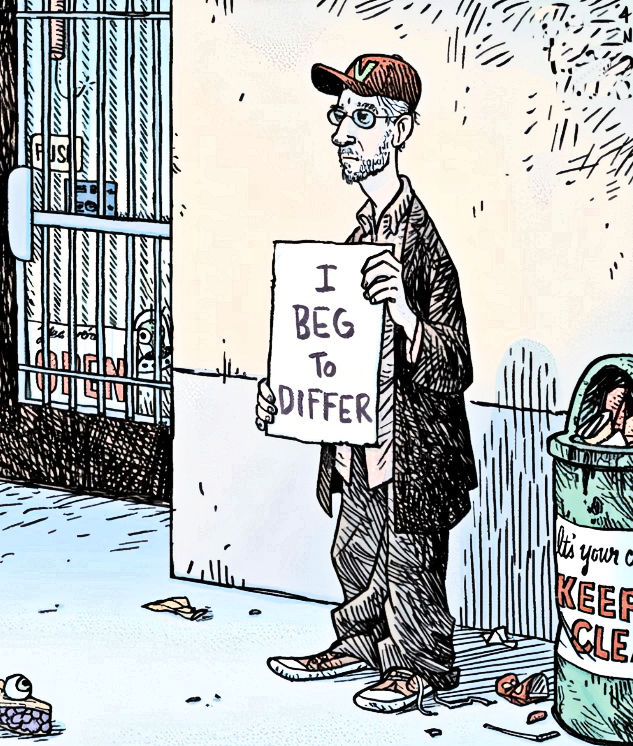

As a result of these two diametrically opposing views, he and I frequently engage in heated discussions over the pros and cons of allowing guns to be available to so many Americans. Although these “discussions” often get heated, neither one of us has allowed the arguments to become uncivil. We have agreed to disagree without inciting animosity. Today, it is more important than ever that all Americans do the same.

Unfortunately, American society in this, the third decade of the twenty-first century, seemingly cannot do what my grandson and I can – agree to disagree. These days it seems that every disagreement results in some form of violent conflict - some verbal and some very physical. Consider the following:

In the Park Slope section of Brooklyn, a Conservative synagogue displayed a huge sign picturing a tallit (Jewish prayer shawl), inscribed with “Black Lives Matter” (BLM). This was very strange sanctification of a movement in which some of its Marxist leaders denounce the “Western-prescribed nuclear family structure.” In the summer, BLM signs adorned the windows of neighborhood townhouses. During the violent race riots in 2020, a City Council Member blasted America’s “structural racism” and admitted that it made him feel “implicated in white supremacy.”

All of this reinforced the conclusion that It is no longer feasible to agree to disagree. The differences that divide the right and left in America have grown exponentially as the left shifts more and more to the extreme left. And extreme left opinions are springboards for increasingly threatening policies.

The Park Slope neighborhood is not a stand-alone urban metropolis of left-wing progressives. It is emblematic of big cities across America. Democrats have voted in leaders who have transformed their progressive agendas into facts on the ground.

Ideology translates into policy and policy has consequences. Misplaced compassion in New York City’s political arena has transformed so-called criminal justice reform into a 97 percent increase in shootings and a 45 percent jump in murders.

Hammering away at “systemic racism” has resulted in violent riots and defunding the police. Together with the failed policies of homeless advocates, the factors that determine quality of life have been removed. People no longer feel safe walking the streets or taking public transportation in many urban areas.

Progressives dream of wealth redistribution in the form of higher taxes and expanded regulation. And with Democratic control of the presidency and both houses of Congress, Democrats have been salivating at the chance to undo Trump’s economic policies.

The proliferation of affirmative action practically guarantees that many whites will have diminished opportunities for graduate schools, should they decide to attend. And if they do, they will have to contend with PC claptrap in the classroom from professors who monitor ideas with the best of thought police and punish diverging ones accordingly.

Whites have to fend off accusations of “privilege” leveled against them, aided by racially divisive falsehoods taught in schools, such as the “1619 Project” or California’s proposed statewide mandatory Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum - an anti-Zionist, anti-white syllabus that faults Jews for their “conditional whiteness” and “racial privilege.”

Social mores are drifting further and further away from biblical injunctions, seeping into and corrupting Judeo-Christian religious domain - affecting schools, institutions, housing, places of employment. All under the guise of discrimination laws. And anyone who dissents is labeled a bigot. So much so that protecting our religious freedoms in the face of irreligious ones has to go all the way to the Supreme Court to seek redress.

With the possible exception of religion, there is nothing as personal or as intense as one’s political beliefs. They define a person’s essence. And as political divisiveness grows in tandem with the disparity between America’s two parties, political identity takes on much more than a worldview.

Against the backdrop of acute discord, the theme of President Biden’s inauguration was “America United.” In his inaugural address, Biden correctly said: “We must end this uncivil war, that pits red against blue, rural against urban, conservative against liberal.”[11] So far in Biden’s term in office, this “uncivil war” has continued unabated, if not intensified.

The red state/blue state divide in America has only served to grow deeper as the extremes of politics move further away from the center. America is no longer an “agree to disagree” country where ideals of freedom and liberty generally won out above all else. With continual pressure from progressive activists to impose more and more government control on the states, there doesn’t seem to be any escaping the numerous ways in which personal liberties can be infringed.

This cuts both ways, of course, since what one state sees as expanding liberty, another sees as impeding progress, and vice versa. How can we solve such a situation? Students in most public schools are not taught to appreciate the country and appreciate differing points of view with respect and decency the way they once were. It’s no longer acceptable to “agree to disagree.” Instead, society has turned into “agree or you must be canceled.”

An interesting poll out of the University of Virginia (UVA) found some shocking numbers when looking at how to bridge the divide in American politics. Perhaps the most fascinating involves the number of people who think it’s time for states to break into separate countries and secede from one another:

The poll revealed that political divisions run so deep in the US that over half of Trump voters wanted red states to secede from the union and 41% of Biden voters wanted blue states to split off.

“The divide between Trump and Biden voters is deep, wide, and dangerous,” the director of UVA’s Center for Politics wrote. “The scope is unprecedented, and it will not be easily fixed.”

The problem with democracy is that it’s messy, and it means many voters will not be happy all the time with the results. That’s a divide that doesn’t exist in totalitarian regimes where it doesn’t matter what the people think. In lieu of a totalitarian takeover, each side is going to have to give a little and hold back on their most extreme policy proposals.

As political divisions sharpen, and the federal government grows in reach under the Democrats’ progressive agenda, this red/blue divide will only serve to deepen.[12] Unless we Americans can quickly agree to disagree, the problems facing us all will continue to grow and to worsen.

Getting back to the differences that my grandson and I have, neither of us has made much progress in changing the other’s mind. He and I remain widely apart in our positions - he being a staunch Pro-Trump right-wing conservative while I remain a middle-of-the road anti-Trump conservative. In spite of the huge gaps in our positions, we speak frequently, never become belligerent or intolerant and we both vigorously and vociferously defend our positions. Without formally stating it, we both have agreed to disagree.

If there's one thing other Americans today seem to agree on, it's that most Americans have totally forgotten how to disagree. A disabling tribalism has infected out country in recent years, one which has us at each other's throats, incapable of recognizing a shared reality, let alone shared values.

One of the values that Americans used to be able to agree on was that agreement was not actually a goal in and of itself. After all, a democracy is not built on sameness but on difference, on tolerance, on diversity. The ability to communicate with people who have strongly held beliefs that are different than our own, and to respect that difference, was once a core American value, and one that today we've sadly lost.

But there remains one thing - the ability to disagree - that alone can heal the torn social fabric that has become so frayed here in America in recent years.

So how can Americans reestablish this value? How can Americans have a respectful debate with someone

who disagrees with their personal politics at a time when the issues seem so urgent, the divide so large, the chasm so

deep?

Maybe the answers to these and similar questions comes when we establish and adhere to some rules.

Here is a set of such rules. My grandson and I have basically followed these rules without ever expressly stating them.

We assume good intentions: Our conversations start from a place of mutual respect.

We both believe that the other wants what is best for each other and for America. At the same time, we recognize that we have

different preferences in how to achieve our objectives. So rather than calling into question each other’s motives, we get

down to the interesting part: probing what means might reach the ends that we are looking for.

In other words, the discussions we have aren't personal; they are about ideas and policies.

We don't try to win at the expense of the other losing: If you see a discussion as a

competition where you need to win and the other person needs to lose, you've pretty much guaranteed failure. Social media has

made us almost paranoid about this, constantly probing for that biting put-down that can embarrass or "DESTROY" the person

with whom we are talking.

In fact, an attempt to win may be harming the ability to persuade. Psychologists have repeatedly

found that listening carefully and calling attention to the nuances in someone else's views can be the only way to help people

moderate the extremism of their opinions and become more open minded.

Avoid "whataboutism": "Whataboutism" is a reminder of bad things in your opponent's

past positions as an excuse to avoid discussing your own side's current malfeasance. It goes something like this: "Oh, you

don't like what President Biden is doing about X? Well, what about when President Trump did Y?" It produces a dead end since

anyone can keep going back and finding bad things that someone on the other side did. To have a productive conversation,

we have to take each event on its own terms.

Get a factual baseline:Too often, we get hung up in conversations because we confuse

what we want to be true with what is true. Take tax cuts, for example. We can ask about a specific policy, "What is this going

to do?" and we can also ask "Is this a good idea?" It's extremely important to be able to answer the first question as

dispassionately as possible before we try to answer the second. One is a question of fact, while the other is a question

of values. We can't let our values replace our facts.

Unfortunately, too many people confuse their values and their facts, which amounts to starting from

a place of believing some actions are good or bad and then reason backwards to predict what these actions will produce.

At the very least, when discussing a policy or law, it is important to know which of those two

questions we are trying to answer.

Agree to disagree: People’s views are unlikely to change because of one conversation.

So, don't bother trying to change the other's mind, at least, not to a great degree. We can hope that the other party

considers from where we are coming, and maybe might temper their views or question some of their assumptions, but we know

at the end we're probably still going to disagree, and that's OK. Hopefully, at the end, we have had a chance to pressure-test

what we think. It's crucial to remember that a healthy society can and must sustain a certain level of debate, not about core

values but about how we achieve them.

Recognize that we might be wrong: If we go into a conversation 100% positive that we

are right and the other party is wrong, there is no point in even talking. If instead we go into a conversation believing that

even if we disagree with the other party, we can learn something from them, and they might have a perspective or information

that we don't currently have, we can have a productive interaction even when we disagree.

Even better, if we are open to the fact that we might not have thought through an issue as thoroughly

as we felt we had, or that we were relying on information that wasn't quite right or intuitions that don't perfectly match the

situation, the other party can help refine and improve what we think and why we think it. But all of that growth and

improvement is predicated on the understanding that we might not be entirely in the right.

We'd all like to think that we are more knowledgeable and better able to understand and articulate

what we believe because of our conversations with each other. Rather than slapping away at the strawmen that are so often

constructed in contemporary political discourse, we all would be better off dealing with real-life, informed, good-hearted,

and passionate people who disagrees with us. In the end, it makes us better.[13]

The American electorate must agree to disagree without rancor and animosity. It is vital since

hostility and distrust between everyday Democrats and Republicans is linked to various negative political and nonpolitical

outcomes, including a decline in partisans’ willingness to compromise, reduced trust in government, and a reluctance to

socialize with, and even talk to members of the other party. We are living the consequences of this extreme polarization now,

from the violence of the Capitol riots to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The United States needs to come together, but

compromising on policy looks increasingly impossible. Neither side wants to be seen as sacrificing their political

principles.

If we are going to reduce the political polarization that today plagues America, our politicians

need to do their part. This will not be easy. Some politicians will be reluctant to forego passionate supporters who are

attracted to vitriolic political content. Others will be afraid that positive overtures to the other party will result in

inevitable backlash. Still, the attempt must be made if America is to resume its democratic and open-minded

ways.[14]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References:

- Gun Violence Hits Home, David Burton, Son of Eliyahu: Article 484, 15 July2021.

- Gun Fanatics Using Trojan Horses to Keep Their Deadly Toys, David Burton,

Son of Eliyahu: Article 375,

30 August 2019.

- The Insanity Continues, David Burton, Son of Eliyahu: Article 362, 3 June 2019.

- America Obfuscates and New Zealand Acts, David Burton, Son of Eliyahu: Article 353,

8 April 2019.

- For Shame, America!, David Burton, Son of Eliyahu: Article 350, 21 February 2019.

- The ONLY Way to End Gun Violence in America, David Burton, Son of Eliyahu: Article 339,

1 November 2018.

- When It Comes to Guns, It’s Business as Usual, David Burton, Son of Eliyahu: Article 319,

19 March 2018.

- When it Comes to Mass Shootings, There are Doers and Then There are Politicians, David Burton,

Son of Eliyahu: Article 318, 8 March 2018.

- The Second Amendment in 2017, David Burton, Son of Eliyahu: Article 292, 1 June 2017.

- Gun Violence - 2022, David Burton, Son of Eliyahu: Article 525, 28 April 2022.

- It’s no longer feasible to agree to disagree, Sara Lehmann, Jewish News Syndicate,

26 January 2021.

- Majority of Trump and Biden Voters Agree: Time For Red and Blue States to Divide, Nate Ashworth,

Election Central, 1 October 2021.

- 6 Rules for Debating Politics in a Polarized America, Allan Katz and Michael McShane,

Newsweek,

3 March 2021.

- To Reduce Political Hostility, Civility Goes Further Than Compromise, Leonie Huddy and Omer Yair,

Behavioral Scientist, 5 April 2021.

|

|