| |

Here in 2021, the Atlanta Braves have won the World Series - some 68 years after they

left Boston, Massachusetts for Milwaukee, Wisconsin and 55 years after the team moved to Atlanta, Georgia.

But long before there was a baseball team called the Atlanta Braves, that National League team was based

in Boston, Massachusetts and went by the name, Boston Braves. Before that Braves franchise moved to Atlanta, Georgia

in 1966, the team resided in Milwaukee, Wisconsin from 1953 to 1966.

In those days, it was not politically incorrect to give names to American sports teams that reflected

a heritage that was derived from our native American indigenous peoples. In those days, it was not considered offensive to give

names to professional sports teams like: Boston Braves, Cleveland Indians, Washington Redskins, Kansas City Chiefs, Chicago

Blackhawks, and Golden State Warriors.

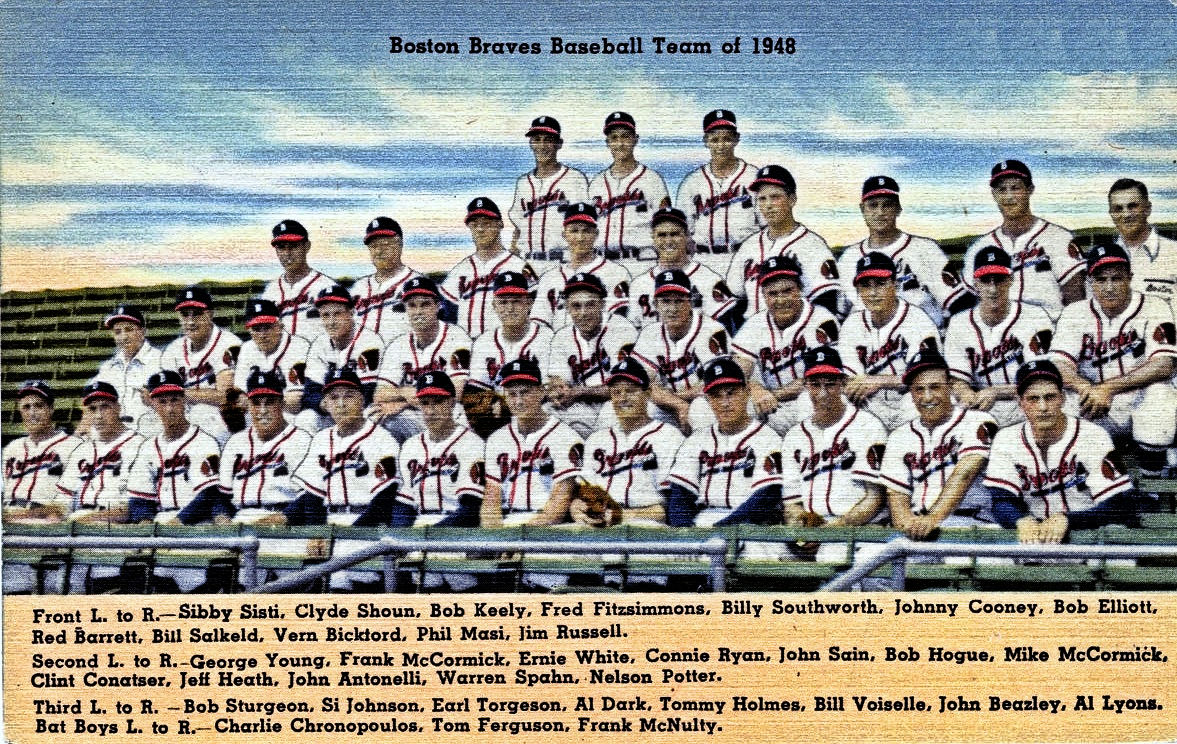

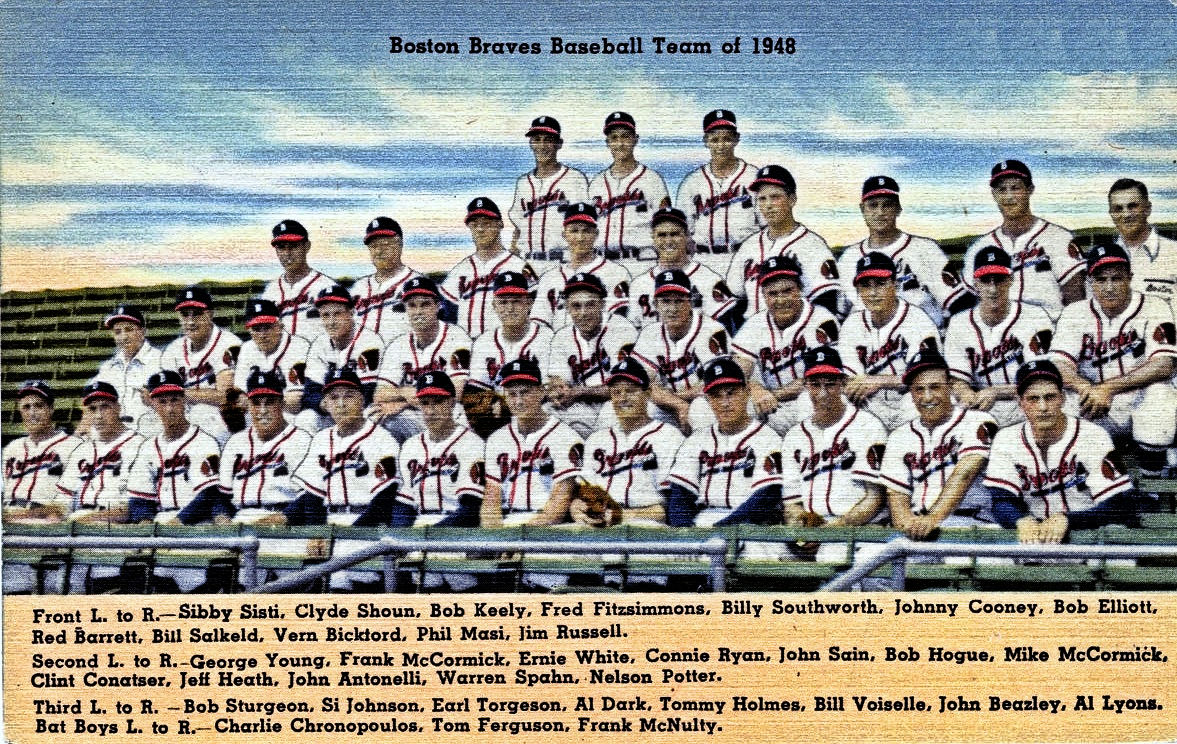

1948 marked the Boston Braves 78th consecutive season as a Major League Baseball franchise, its 73rd

in the National League. 1948 also produced the team's second NL pennant of the 20th century, its first since 1914, and its

tenth overall league title dating back to 1876.

Led by starting pitchers Johnny Sain and Warren Spahn (who combined for 39 victories), and the hitting

of 3rd baseman Bob Elliott, outfielders Jeff Heath and Tommy Holmes, and rookie shortstop Alvin Dark, the 1948 Braves won 91

games to finish 61/2 games ahead of the

second-place St. Louis Cardinals. They also attracted 1,455,439 fans to Braves Field, the third-largest gate in the National

League and a high-water mark for the team's stay in Boston. The 1948 pennant was the fourth National League championship in

seven years for Braves' manager Billy Southworth, who had won three NL titles (1942–44, inclusive) and two World Series

championships (1942 and 1944) with the St. Louis Cardinals. Southworth would be posthumously elected to the Baseball Hall of

Fame as a manager in 2008.

After 1948, the Braves experienced a swift decline in both on-field success and popularity over the

next four seasons. Attendance woes - the Braves would draw only 281,278 home fans in 1952 - forced the team's relocation to

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in March 1953 (and later its moving to Atlanta in 1966.)[1]

Following World War II, the Boston Braves tended to take second place in the hearts of baseball fans

in Boston, playing second fiddle to the Boston Red Sox. My Uncle Sam was an exception. He was a die-hard Braves fan who would

take me out to the old Braves Field (now Nickerson Field on the campus of Boston University) on Commonwealth Avenue to watch a

Braves game. We would always take public transportation, with the last leg of our trip being on a Commonwealth Avenue street

car that would deposit us right outside the ball park.

Warren Spahn and Johnny Sain

I remember the year 1948 – I was twelve years old back then – when to the great joy of some Boston

fans, the Boston Braves won the pennant in the National League and faced the Cleveland Indians and Bob Feller in the World

Series. The Braves’ pitching, outside of Warren Spahn and Johnny Sain, was a bit suspect, but as recorded in the poem

Spahn & Sain by Gerald V. Hern, there was a solution to the pitching problem.

First we'll use Spahn

then we'll use Sain

Then an off day

followed by rain

Back will come Spahn

followed by Sain

And followed

we hope

by two days of rain. (Ref. 2)

Following the publication of the poem, the cries went up from Braves’ fans: “Spahn and Sain and

two days of rain” or “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain”. There are those of us who still remember those cries.

Unfortunately, the Braves lost the World Series to the Cleveland Indians in six games.

In an unbelievable stretch of 12 days that year, beginning with a Labor Day doubleheader, Spahn and

Sain had won eight games without losing. On Labor Day, Spahn won the first game of the twin bill, pitching 14 innings and Sain

came back and won the second game. There followed 2 days off for rain and Spahn won the next day and Sain pitched the win the

following day. Three days later, Spahn won again and Sain won the next day. Then, after a day off, Spahn won the first game of

a doubleheader and Sain won the second.

This may have not been the greatest achievement by a pitching twosome in the history of the game but

it’s doubtful if any pair ever put together such a stretch. Going into Labor Day, the Braves had a 2 ½ game lead over the

Brooklyn Dodgers and St. Louis Cardinals but ended the season with a 91-62 record, 6 ½ games ahead of the second place

Cardinals.

In the World Series, Sain bested Bob Feller in the first game throwing a complete game 2 hit shutout

to win 1-0. Spahn took the loss in Game 2 lasting only 4 innings as Cleveland tied the series at 1-1. Cleveland won game 3 by a

2-0 score and Sain came back in game 4 and went all the way but lost 2-1. The Braves stayed alive in game 5 winning 11-5, with

Spahn throwing the last four innings in relief. A crowd of 86,288, the largest in World Series history to date, watched this

game in Cleveland. Cleveland went on to win the series, taking game 6, 4-3 with Spahn again coming on in relief in the eighth.

For the series, Spahn and Sain were each 1-1 with Sain pitching 17 innings and ging up just 2 runs. Spahn pitched 12 innings,

giving up 4 runs. In the 6-game series either Spahn or Sain appeared in all but one game.

Today in Major League baseball, pitchers rarely pitch more than 5 or 6 innings – complete games are

an extremely rare occurrence. But in that 1948 season, Warren Spahn pitched 16 complete games and 257 innings and

Johnny Sain threw an amazing 28 complete games and 315 innings. That year, 1948, the pair won 39 games while losing

27.[3]

The Starting Players

In addition to the pitching of Spahn and Sain, the hitting of outfielders Jeff Heath and Tommy Holmes,

along with that of 3rd baseman Bob Elliott, and rookie shortstop Alvin Dark were key factors in the Braves making it to the

1948 World series.

Other starting players on the 1948 team were: Earl Torgeson – 1st base; Eddie Stanky, 2nd Base; Phil

Masi, catcher; and Jim Russell, Outfielder.

While the Braves were winning the National League pennant, Boston’s American League team, the Red Sox,

ended their season in a first-place tie with the Cleveland Indians and lost the playoff game to Cleveland at Fenway Park,

ruining the prospect of what would have been the only all-Boston World Series in Major League Baseball history.

[4]

Television Comes to Boston Baseball

The 1948 baseball season was notable for both the Braves and the Red Sox. 1948 marked the first season

in which their games were broadcast on television, with telecasts alternating between WBZ-TV and WNAC-TV. The two teams shared

the same announcers. The first-ever telecast of a major league game in New England occurred on Tuesday night, 15 June 1948,

with the Braves defeating the visiting Chicago Cubs 6–3 behind Sain's complete game.[4]

The two announcers who telecast the Braves (and Red Sox) games were Jim Britt & Tom Hussey.

On 15 June 15 1948, Britt was at the microphone on WBZ-TV for the first live telecast of a Major League game in New

England.[5]

The Jimmy Fund

The 1948 Boston Braves were memorable for another very notable reason besides making it to the world

series.

In 1947, in the basement of what is now Boston Children’s Hospital, Sidney Farber, M.D., was working

in a one-room laboratory probing the mysteries of leukemia — a cancer that was then 100 percent fatal for children and adults.

Late that year, he found a drug that achieved temporary remissions in 10 of 16 pediatric patients, and his findings were

reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in the spring of 1948.

Members of the Variety Club of New England, a social and charitable organization connected with the

theater and entertainment industry, were looking for worthy causes to support financially. When they heard about Dr. Farber’s

findings, they decided to back his cause. Their fundraising efforts resulted in the formation of the Children’s Cancer Research

Foundation, or CCRF (now known as Dana-Farber Cancer Institute). Next, hoping to bankroll a state-of-the-art research

and treatment facility for Dr. Farber, the Variety Club came up with a unique and winning idea.

They arranged for a live nationwide broadcast of the popular Saturday night radio game show Truth

or Consequences to be aired in part from the hospital bedside of one of Dr. Farber’s patients. The show’s host, Ralph

Edwards, asked questions in front of his California audience and they were heard and answered in Boston Children’s Hospital

by Einar Gustafson, a 12-year-old boy whom Dr. Farber had dubbed “Jimmy” to protect his privacy. Gustafson, from Maine, was

being treated for a form of cancer that was then fatal in about 85 percent of pediatric patients.

Hearing that Gustafson’s favorite team was the Boston Braves, the Variety Club worked with Braves

publicity director Billy Sullivan to arrange for members of the club to surprise Gustafson with a visit to his room during

the live broadcast. After a 6-4 loss to the St. Louis Cardinals that afternoon at Braves Field, players changed into their

street clothes and made the trip to the hospital. There they were met by Sullivan and representatives from the Variety Club,

who led them to Gustafson’s room, where microphones had been hooked up beforehand.

The crowd in Hollywood and listeners around the country heard Gustafson - known only as “Jimmy” -

grow increasingly excited as players arrived one-by-one at his bedside with autographed balls, bats, and jerseys. Braves

manager Billy Southworth came last with an authentic woolen team uniform tailored to Gustafson’s size. Southworth invited

Gustafson out to the next day’s doubleheader at Braves Field against the Cubs, and after the radio feed from Boston went out,

Edwards made an appeal to listeners: If $20,000 could be raised for the CCRF, “Jimmy” would receive a television set on which

to watch Braves games.

Before the broadcast had even ended, listeners who heard it on their car radios were driving up to

the front of Boston Children’s Hospital and handing coins and dollar bills over at the front desk. In the days to come

thousands of envelopes marked “Jimmy – Boston, Mass.” arrived at the hospital stuffed with change, and Braves players

attended picnics, car washes, and other fundraising events that brought in more cash. Gustafson soon got his TV, and by

summer’s end, more than a quarter million dollars was raised for the “Jimmy Fund.”

Due to the grim statistics then associated with all children’s cancers, Gustafson was not expected

to survive. But as the Braves did in recovering from early-season mediocrity to move into first place in mid-June and

eventually win the pennant, the boy rallied. Gustafson was home on his family farm by that fall, and the tremendous

fundraising surrounding his radio appearance was the springboard for the construction of a four-story cancer research and

treatment center for Dr. Sidney Farber and the CCRF. Located less than a block from Boston Children’s Hospital, it was

named — appropriately — the Jimmy Fund Building.

Einar “Jimmy” Gustafson lived out of the spotlight, and presumed dead by almost all but his hometown

and Dr. Farber, Gustafson grew up to be a father of three, a grandfather of six, and a long-distance truck driver. In 1998 he

emerged from a half-century of silence to help the Jimmy Fund celebrate its 50th anniversary.

His was not the only happy ending. The most common childhood leukemia is now 90 percent curable, and

survival rates for many other pediatric and adult forms of the disease continue making extraordinary gains — thanks in large

part to the night a group of weary ballplayers stopped in to make a sick little boy happy.

[6]

Braves Field

Braves Field, the home of the 1948 Boston Braves, was the last and largest of the first wave of

concrete-and-steel ballparks built between 1909 and 1915. Owner James Gaffney built a wide open ballpark conducive to

inside-the-park home runs. A covered single-deck grandstand seating 18,000 wrapped around the diamond from well down each

foul line. Two uncovered pavilions seating 10,000 apiece occupied the areas just past the grandstand up to the foul

poles. The Jury Box, as it was called after a sportswriter noticed during a game that only 12 spectators were

sitting in the section, seated 2,000 and was located in right field.

With the advent of the lively ball, baseball became a game of over-the-fence home runs for which

Braves Field was ill equipped. So, in 1928 the fences were moved in and subsequently tweaked for years thereafter. After the

Braves left in 1953, Boston University purchased the property, converted it for football and changed its name to Nickerson

Field, where the B.U. Terriers played football until 1997. Field hockey and soccer games as well as commencement ceremonies

are still held there. The old right-field pavilion has been incorporated into Nickerson's seating arrangement. The left field

pavilion was replaced by an arena and the grandstand was replaced by three high-rise dormitory buildings. The first base ticket

office and the concrete outer wall in right and center field are still standing.[7]

The Three Little Steam Shovels

The 1948 Boston Braves were owned by the “Three Little Steam Shovels” who took over ownership of

the club in 1944. These “Three Little Steam Shovels” were Lou Perini, Guido Rugo and Joseph Maney and were contractors in

real life.[8]

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References:

- 1948 Boston Braves season, WikiMili, 28 April 2021.

- Spahn & Sain, Gerald V. Hern, Boston Post, 14 September 1948.

- SPAHN, SAIN AND PRAY FOR RAIN!!!!, Carl H. Johnson, BASEBALL WORLD, 9 June 2015.

- 1948 Boston Braves season, Wikipedia, 28 April 2021.

- Jim Britt, Wikipedia, 28 July 2021.

- May 23, 1948: Boston Braves win two for Jimmy Fund, Saul Wisnia, SABR, Society for American

Baseball Research, Accessed 10 October 2021.

- Braves Field, ballparks.com, June 2006.

- Atlanta Braves History: The Three Little Steam Shovels (1944), Michael Wilson,

thebraveshistory.wordpress.com, 18 April 2013.

|

|