| |

In the 1930's THE SPENCER PRESS published some twenty volumes of literary

classics. These books were intended to have "a cultural and educational background that would tend

to broaden the vision and develop the inner resources of the reader . . . books that were

sufficiently thrilling and popular in their appeal to capture the imagination and interest of

every member of the family." (Ref. 1)

Some five volumes of these books existed in the bookcase of my parents

and made it into my library after their deaths. I was born in 1936, but had never taken an interest

in reading them. However, in October of 2019, I belatedly decided to read The Autobiography

of Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard’s Almanac and Other Papers which was published in

the year I was born, by THE SPENCER PRESS. Included in this text was an article from POOR

RICHARD’S ALMANAC which Franklin wrote in 1780 when he was 74 years old, suffering from the

gout and living, at that time, in France.

Franklin often took on problems of his time, including his personal

problems, with humor. One of his personal problems was gout, from which he suffered throughout

his life, and which caused him tremendous discomfort in his legs and feet. During one particularly

painful attack, Franklin wrote an imaginary dialogue between "Madam Gout" and himself. His advice

from "Madam Gout" is as relevant to good health today as it was at the time Franklin composed the

dialogue. Read what Benjamin Franklin advised nearly 230 years ago and decide for yourself. You

may also want to decide whether or not Franklin deserved the title of "First American

Humorist".

"Franklin developed a satirical style of writing that examined the

political, personal, and social issues of the time. Whether he was poking fun at conservative

Bostonians or laughing at the battle of the sexes, Franklin's style was entertaining, but carried

a message. His satirical pieces 'made 'em laugh' but also 'made 'em think.' "

(Ref. 2)

When Benjamin Franklin served as the American Ambassador to France, he

lived in Passy near the unfortunate Princesse de Lamballe, another gout sufferer. The Dialogue

Between Franklin and the Gout refers to this period of his life in France. Here's the

Dialogue Between Franklin and the Gout as written by Franklin and reproduced in

Reference 3.

{This playful conversation by Benjamin Franklin is excerpted from a collection

published in 1914, The Oxford Book of American Essays, chosen by Brander

Matthews.}

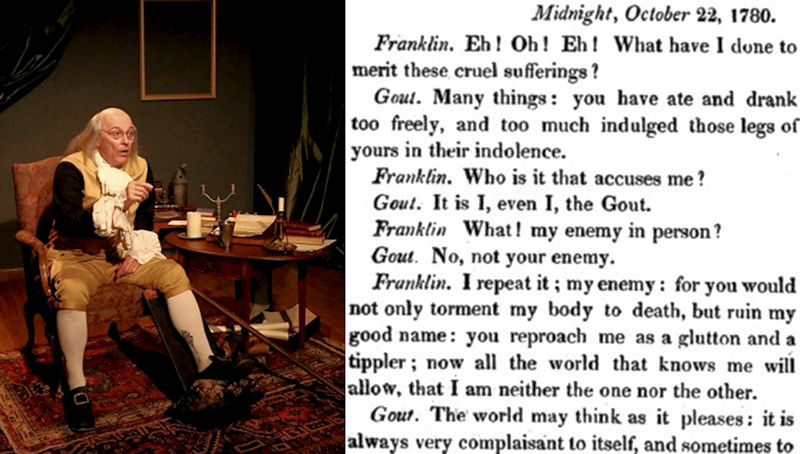

Midnight, 22 October, 1780

FRANKLIN. Eh! Oh! eh! What have I done to merit these cruel sufferings?

GOUT. Many things; you have ate and drank too freely, and too much indulged those

legs of yours in their indolence.

FRANKLIN. Who is it that accuses me?

GOUT. It is I, even I, the GOUT.

FRANKLIN. What! my enemy in person?

GOUT. No, not your enemy.

FRANKLIN. I repeat it, my enemy; for you would not only torment my body to death,

but ruin my good name; you reproach me as a glutton and a tippler; now all the world, that knows

me, will allow that I am neither the one nor the other.

GOUT. The world may think as it pleases; it is always very complaisant to itself,

and sometimes to its friends; but I very well know that the quantity of meat and drink proper for

a man, who takes a reasonable degree of exercise, would be too much for another, who never takes

any.

FRANKLIN. I take—eh! oh!—as much exercise—eh!—as I can, Madam GOUT.

You know my sedentary state, and on that account, it would seem, Madam GOUT, as if

you might spare me a little, seeing it is not altogether my own fault.

GOUT. Not a jot; your rhetoric and your politeness are thrown away; your apology

avails nothing. If your situation in life is a sedentary one, your amusements, your recreation,

at least, should be active. You ought to walk or ride; or, if the weather prevents that, play at

billiards. But let us examine your course of life. While the mornings are long, and you have

leisure to go abroad, what do you do? Why, instead of gaining an appetite for breakfast, by

salutary exercise, you amuse yourself with books, pamphlets, or newspapers, which commonly are

not worth the reading. Yet you eat an inordinate breakfast, four dishes of tea, with cream, and

one or two buttered toasts, with slices of hung beef, which I fancy are not things the most

easily digested. Immediately afterwards you sit down to write at your desk, or converse with

persons who apply to you on business. Thus the time passes till one, without any kind of bodily

exercise. But all this I could pardon, in regard, as you say, to your sedentary condition. But

what is your practice after dinner? Walking in the beautiful gardens of those friends with whom

you have dined would be the choice of men of sense; yours is to be fixed down to chess, where you

are found engaged for two or three hours! This is your perpetual recreation, which is the least

eligible of any for a sedentary man, because, instead of accelerating the motion of the fluids,

the rigid attention it requires helps to retard the circulation and obstruct internal secretions.

Wrapt in the speculations of this wretched game, you destroy your constitution. What can be

expected from such a course of living, but a body replete with stagnant humors, ready to fall

prey to all kinds of dangerous maladies, if I, the GOUT, did not occasionally

bring you relief by agitating those humors, and so purifying or dissipating them? If it was in

some nook or alley in Paris, deprived of walks, that you played awhile at chess after dinner,

this might be excusable; but the same taste prevails with you in Passy, Auteuil, Montmartre, or

Sanoy, places where there are the finest gardens and walks, a pure air, beautiful women, and

most agreeable and instructive conversation; all which you might enjoy by frequenting the walks.

But these are rejected for this abominable game of chess. Fie, then, Mr. Franklin! But amidst my

instructions, I had almost forgot to administer my wholesome corrections; so take that twinge,

—and that.

FRANKLIN. Oh! eh! oh! Ohhh! As much instruction as you please, Madam

GOUT, and as many reproaches; but pray, Madam, a truce with your

corrections!

GOUT. No, Sir, no, - I will not abate a particle of what is so much for your

good, - therefore --

FRANKLIN. Oh! ehhh!—It is not fair to say I take no exercise, when I do very

often, going out to dine and returning in my carriage.

GOUT. That, of all imaginable exercises, is the most slight and insignificant,

if you allude to the motion of a carriage suspended on springs. By observing the degree of heat

obtained by different kinds of motion, we may form an estimate of the quantity of exercise given

by each. Thus, for example, if you turn out to walk in winter with cold feet, in an hour’s time

you will be in a glow all over; ride on horseback, the same effect will scarcely be perceived by

four hours' round trotting; but if you loll in a carriage, such as you have mentioned, you may

travel all day and gladly enter the last inn to warm your feet by a fire. Flatter yourself then

no longer, that half an hour’s airing in your carriage deserves the name of exercise. Providence

has appointed few to roll in carriages, while he has given to all a pair of legs, which are

machines infinitely more commodious and serviceable. Be grateful, then, and make a proper use

of yours. Would you know how they forward the circulation of your fluids, in the very action of

transporting you from place to place; observe when you walk, that all your weight is alternately

thrown from one leg to the other; this occasions a great pressure on the vessels of the foot,

and repels their contents; when relieved, by the weight being thrown on the other foot, the

vessels of the first are allowed to replenish, and, by a return of this weight, this repulsion

again succeeds; thus accelerating the circulation of the blood. The heat produced in any given

time depends on the degree of this acceleration; the fluids are shaken, the humors attenuated,

the secretions facilitated, and all goes well; the cheeks are ruddy, and health is established.

Behold your fair friend at Auteuil; a lady who received from bounteous nature more really useful

science than half a dozen such pretenders to philosophy as you have been able to extract from all

your books. When she honors you with a visit, it is on foot. She walks all hours of the day, and

leaves indolence, and its concomitant maladies, to be endured by her horses. In this, see at once

the preservative of her health and personal charms. But when you go to Auteuil, you must have your

carriage, though it is no farther from Passy to Auteuil than from Auteuil to Passy.

FRANKLIN. Your reasonings grow very tiresome.

GOUT. I stand corrected. I will be silent and continue my office; take that,

and that.

FRANKLIN. Oh! Ohh! Talk on, I pray you.

GOUT. No, no; I have a good number of twinges for you to-night, and you may be

sure of some more to-morrow.

FRANKLIN. What, with such a fever! I shall go distracted. Oh! eh! Can no one

bear it for me?

GOUT. Ask that of your horses; they have served you faithfully.

FRANKLIN. How can you so cruelly sport with my torments?

GOUT. Sport! I am very serious. I have here a list of offenses against your own

health distinctly written, and can justify every stroke inflicted on you.

FRANKLIN. Read it then.

GOUT. It is too long a detail; but I will briefly mention some

particulars.

FRANKLIN. Proceed. I am all attention.

GOUT. Do you remember how often you have promised yourself, the following

morning, a walk in the grove of Boulogne, in the garden de la Muette, or in your own garden,

nd have violated your promise, alleging, at one time, it was too cold, at another too warm,

too windy, too moist, or what else you pleased; when in truth it was too nothing, but your

insuperable love of ease?

FRANKLIN. That I confess may have happened occasionally, probably ten times

in a year.

GOUT. Your confession is very far short of the truth; the gross amount is

one hundred and ninety-nine times.

FRANKLIN. Is it possible?

GOUT. So possible, that it is fact; you may rely on the accuracy of my statement.

You know M. Brillon’s gardens, and what fine walks they contain; you know the handsome flight of

an hundred steps, which lead from the terrace above to the lawn below. You have been in the

practice of visiting this amiable family twice a week, after dinner, and it is a maxim of

your own, that "a man may take as much exercise in walking a mile, up and down stairs, as in

ten on level ground." What an opportunity was here for you to have had exercise in both these

ways! Did you embrace it, and how often?

FRANKLIN. I cannot immediately answer that question.

GOUT. I will do it for you; not once.

FRANKLIN. Not once?

GOUT. Even so. During the summer you went there at six o’clock. You found the

charming lady, with her lovely children and friends, eager to walk with you, and entertain you

with their agreeable conversation; and what has been your choice? Why, to sit on the terrace,

satisfy yourself with the fine prospect, and passing your eye over the beauties of the garden

below, without taking one step to descend and walk about in them. On the contrary, you call for

tea and the chess-board; and lo! you are occupied in your seat till nine o’clock, and that

besides two hours' play after dinner; and then, instead of walking home, which would have

bestirred you a little, you step into your carriage. How absurd to suppose that all this

carelessness can be reconcilable with health, without my interposition!

FRANKLIN. I am convinced now of the justness of Poor Richard’s remark, that

"Our debts and our sins are always greater than we think for."

GOUT. So it is. You philosophers are sages in your maxims, and fools in your

conduct.

FRANKLIN. But do you charge among my crimes, that I return in a carriage from

M. Brillon’s?

GOUT. Certainly; for, having been seated all the while, you cannot object the

fatigue of the day, and cannot want therefore the relief of a carriage.

FRANKLIN. What then would you have me do with my carriage?

GOUT. Burn it if you choose; you would at least get heat out of it once in

this way; or, if you dislike that proposal, here’s another for you; observe the poor peasants,

who work in the vineyards and grounds about the villages of Passy, Auteuil, Chaillot, etc.; you

may find every day among these deserving creatures, four or five old men and women, bent and

perhaps crippled by weight of years, and too long and too great labor. After a most fatiguing

day, these people have to trudge a mile or two to their smoky huts. Order your coachman to set

them down. This is an act that will be good for your soul; and, at the same time, after your

visit to the Brillons, if you return on foot, that will be good for your body.

FRANKLIN. Ah! how tiresome you are!

GOUT. Well, then, to my office; it should not be forgotten that I am your

physician. There.

FRANKLIN. Ohhh! what a devil of a physician!

GOUT. How ungrateful you are to say so! Is it not I who, in the character of

your physician, have saved you from the palsy, dropsy, and apoplexy? one or other of which

would have done for you long ago, but for me.

FRANKLIN. I submit, and thank you for the past, but entreat the discontinuance

of your visits for the future; for, in my mind, one had better die than be cured so dolefully.

Permit me just to hint, that I have also not been unfriendly to you. I never feed physician or

quack of any kind, to enter the list against you; if then you do not leave me to my repose, it

may be said you are ungrateful too.

GOUT. I can scarcely acknowledge that as any objection. As to quacks, I despise

them; they may kill you indeed, but cannot injure me. And, as to regular physicians, they are at

last convinced that the gout, in such a subject as you are, is no disease, but a

remedy; and wherefore cure a remedy?—but to our business,—there.

FRANKLIN. Oh! oh!—for Heaven’s sake leave me! and I promise faithfully never

more to play at chess, but to take exercise daily, and live temperately.

GOUT. I know you too well. You promise fair; but, after a few months of good

health, you will return to your old habits; your fine promises will be forgotten like the forms

of the last year’s clouds. Let us then finish the account, and I will go. But I leave you with

an assurance of visiting you again at a proper time and place; for my object is your good, and

you are sensible now that I am your real friend.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References:

- WORLD’S GREATEST LITERATURE: Autobiography of BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, Benjamin Franklin,

The Spencer Press, 1936.

- Benjamin Franklin . Wit and Wisdom . Franklin Funnies, pbs.org,

2002.

- Dialogue Between Franklin and the GOUT, Benjamin Franklin,

americanliterature.com, Accessed 22 October 2019.

|

|