| |

Over 2,000 years ago, the ancient Israelites were thrown out of their homeland in Israel. Previously, they had been

twice evicted from their homeland that they had conquered after a 40-year march from bondage in Egypt.

For the second time, the Israelites’ Holy Temple atop the Temple Mount was destroyed.

At this time, the Israelite’s homeland had been renamed Palestina by the Romans, who had first conquered Israel

and then ejected the Israelites from their homeland when they revolted against the Roman rule.

The unsuccessful Israelite revolt against Roman rule had been led by Simon bar Kokhba in 132 CE and lasted

until 135 or early 136.[1]

In 1948, after, 2,000 of exile, the Israelites returned to their ancient homeland and,under the auspices of the

United Nations, reestablished their nation, naming it the State of Israel

“The State of Israel was formally established by the Israeli Declaration of Independence on May 14, 1948.

The United Nations (UN) approved a plan to partition Palestine into a Jewish and Arab state in 1947, allowing for the formation of the Jewish

state of Israel. Israel was admitted to the United Nations as a full member state on May 11, 1949.”

(Ref. 2)

In 2024, as protests against Israel spread across college campuses in the fall and spring, the same curious phraseology

kept turning up again and again. Protestors demanded “an immediate end to Israel’s lethal settler-colonial project.” A University of California

professor hailed So-called “Palestinians” as “a non-white, non-European people struggling for liberation and freedom against a settler colonial

oppressor.” A speaker at Harvard University protests called the “Zionist state” an “agent of genocide, apartheid, and settler colonialism.”

“Settler-colonialism” had suddenly burst into public view. The broad meaning was clear. “Settler colonialism” refers to

the genocidal displacement of indigenous populations and their replacement with settlers.

The cases in the academic literature were Australia and the Americas, where European settlers killed large numbers of

aboriginal peoples over centuries and seized their lands. In recent years, the focus had mistakenly shifted to Israel, which justly infuriated the

country’s defenders and more than a few neutral observers.

Israel is an entirely different case, because the Jewish people came to their ancestral home not as colonists but as

refugees and as descendants of the ancient Israelites who had conquered and occupied the Holy Land prior to their expulsion by the Romans 2,000

years ago.

Unlike colonists in Australia and America, the returning Israelites did not decimate the region’s Arab population;

today, there are about 7 million Arabs and 7 million Jews between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River. What is all too-often often

ignored is the fact that the Jewish people have an incontrovertible claim to indigenous status. Indeed, settler-colonial studies might find

in Zionism an archetype of the kind of decolonization it hopes for in America.

A people that defined itself for centuries by its relationship to the land was driven out “by a mighty and ruthless

empire,” the Romans. For a hundred generations, it prayed for a restoration. Then, he writes, Zionism “translated this ancient spiritual

aspiration into modern political terms and finally succeeded in restoring a remnant of the Jewish people to their aboriginal

territory.[3]

The return of the Israelites to the ancient Jewish homeland in 1948 was the second return to Zion. This return to Zion is

described is an event recorded in the Hebrew Bible, in which the Jews of the Kingdom of Judah - subjugated by the Neo-Babylonian Empire - were

freed from the Babylonian captivity following the Persian conquest of Babylon. In 539 BCE, the Persian king Cyrus the Great issued the Edict of

Cyrus allowing the Jews to return to Jerusalem and the Land of Judah, which was made a self-governing Jewish province under the new Persian

Empire.

The Persian period marked the onset of the Second Temple period in Jewish history. Zerubabel, appointed as governor of

Judah by the Persian king, oversaw the construction of the Second Temple.[4]

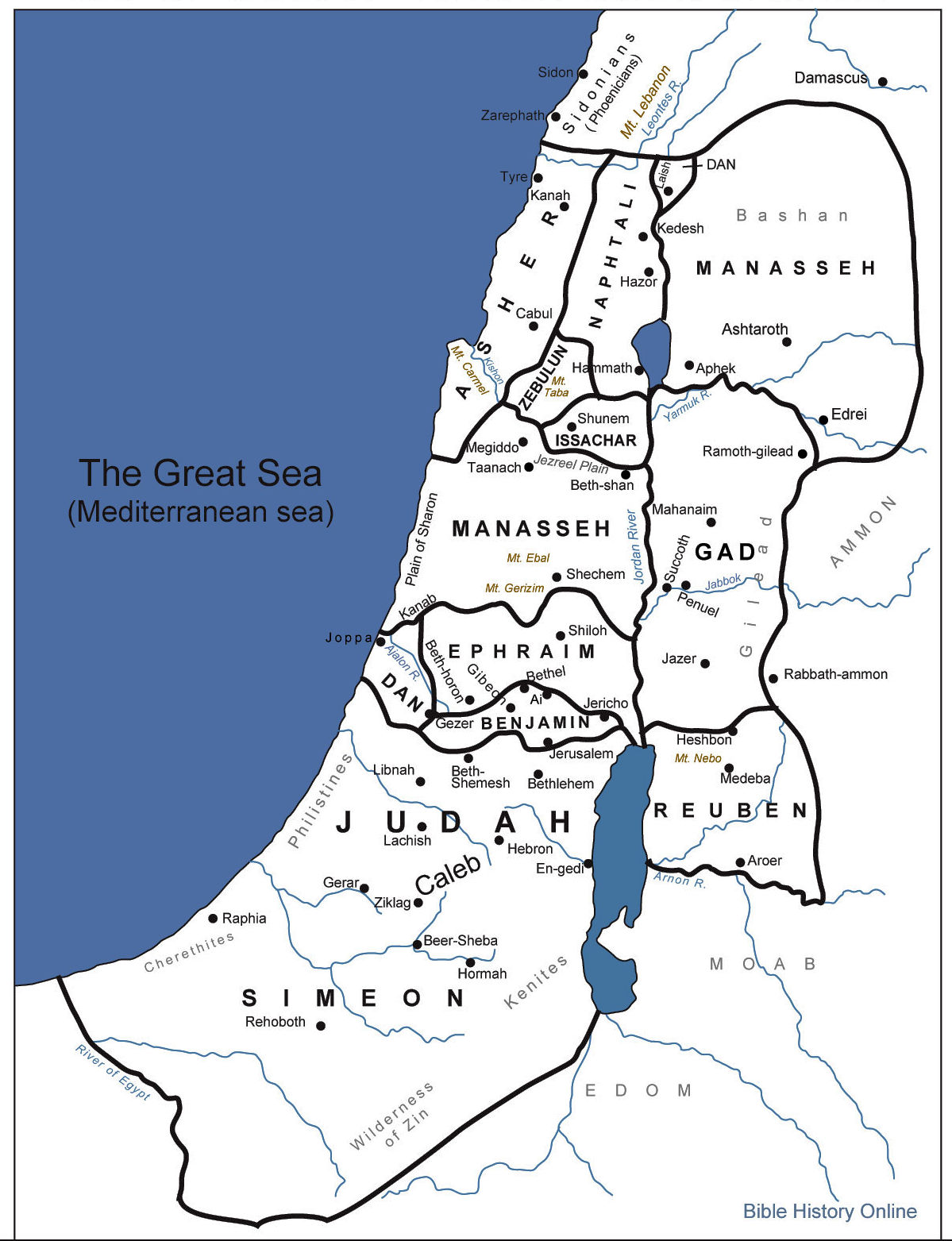

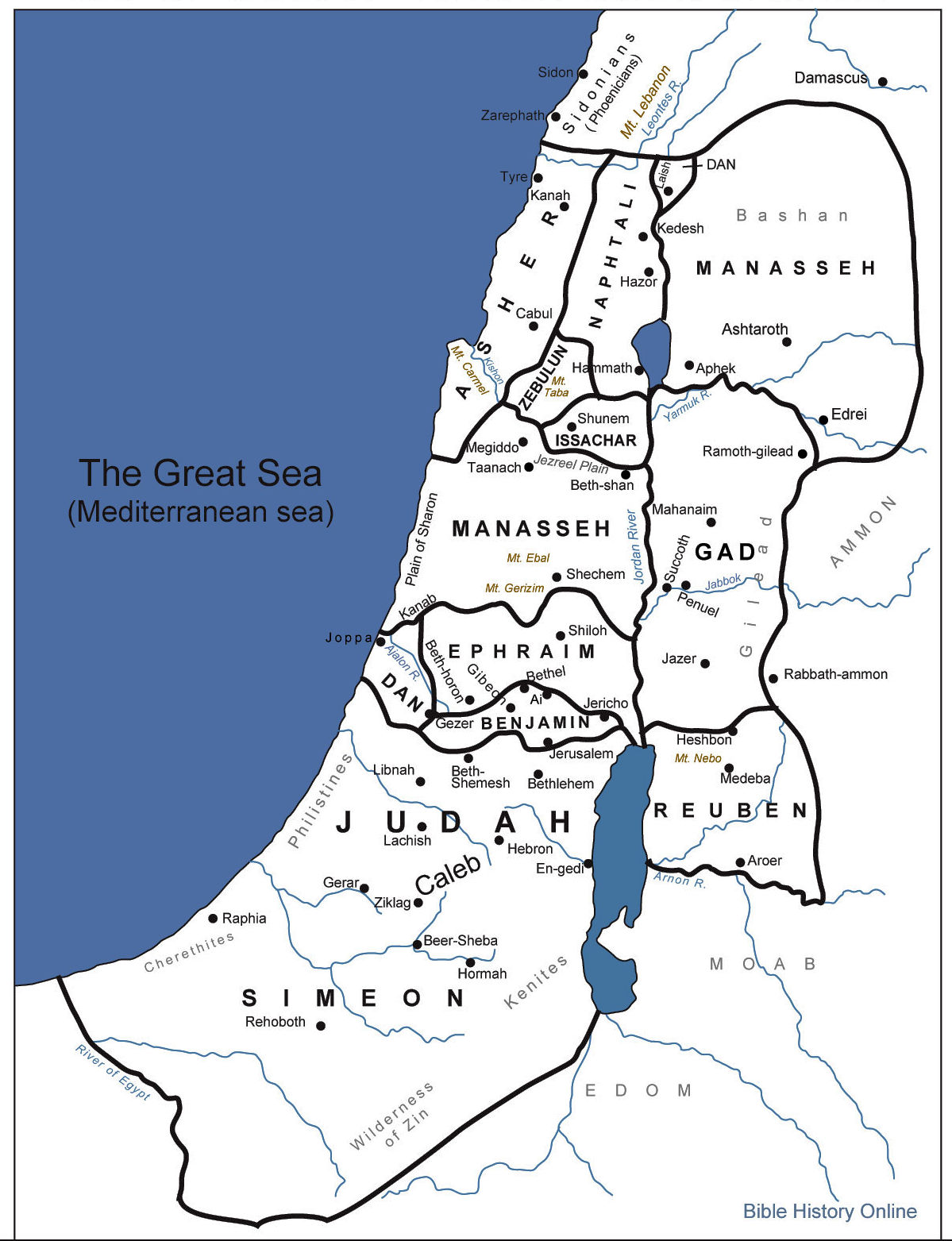

The land on which the State of Israel exists today and which is the homeland of the Jewish people was conquered in the

13th century BCE, by the Israelites and their leader, Jushua, following the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt. The arrival of the

Israelites in the Land if Israel occurred more than 3,000 years Ago. There are no Canaanites remaining in what became Palestine.

Today, the closest there is to an “indigenous Palestinian people” are the descendants of the Israelites that defeated the Canaanites and

took the land from them.

Canaan, is an area variously defined in historical and biblical literature, but always located in what came to be known

as Palestine. Its original pre-Israelite inhabitants were called Canaanites. The names Canaan and Canaanite occur in cuneiform, Egyptian, and

Phoenician writings from about the 15th century BCE as well as in the Old Testament. In these sources, “Canaan” refers sometimes to an area

encompassing all of Palestine and Syria, sometimes only to the land west of the Jordan River, and sometimes just to a strip of coastal land from

Acre (?Akko) northward. The Israelites occupied and conquered Palestine, or Canaan, beginning in the late 2nd millennium BCE, or perhaps earlier;

and the Bible justifies such occupation by identifying Canaan with the “Promised Land”, the land promised to the Israelites by

God.[5]

While the region known as Palestine was home to the Hebrew people or Israelites for more than three thousand years, it

was never home to an Arabic people until the time of the British Mandate after the First World War in the early 20th century. The so-called

Palestinian people are an ethnonational group with family origins in the region of Palestine. Only since 1964, have they (incorrectly) been

referred to as Palestinians, but before that they were usually referred to as Palestinian-Arabs. Note that during the period of the

British Mandate, the term Palestinian was also used to describe the Jewish community living in Palestine.

Prior to the British Mandate, Palestine was under the control of the Turkish-Ottomans and Palestine's Arab population

mostly saw themselves as Ottoman subjects.

In 1882 the population numbered approximately 320,000 people, 25,000 of whom were Jewish. At the beginning of the

20th century, a "local and specific Palestinian patriotism" emerged. When the First Palestinian Congress of February 1919 issued its anti-Zionist

manifesto rejecting Zionist immigration, it extended a welcome to those Jews "among us who have been Arabicized, who have been living in our

province since before the war; they are as we are, and their loyalties are our own." Palestinian-Arab nationalism as a distinct movement first

appeared between April and July 1920.

When Zionism began taking root among Jewish communities in Europe, many Jews emigrated to Palestine and established

settlements there. When Palestinian-Arabs concerned themselves with Zionists, they generally assumed the movement would fail. In the early 1900’s,

Arab Nationalism grew rapidly in the area and most Arab Nationalists regarded Zionism as a threat, although a minority perceived Zionism as

providing a path to modernity. Though there had already been Arab protests to the Ottoman authorities in the 1880s against land sales to

foreign Jews, the most serious opposition began in the 1890s after the full scope of the Zionist enterprise became known. There was a general

sense of threat. The creation of the “British Mandate of Palestine” in 1918 and the “Balfour Declaration” greatly increased Arab fears.

Palestine was made a separate state within the British sphere, earmarked as a national home for the Jews. A flood of

poor Jewish immigrants poured into the promised land and was speedily involved in serious conflicts with the Arab population.

The Palestinian-Arabs felt ignored by the terms of the Mandate. Though having civil and religious rights, they were not

given any national or political rights. As far as the “League of Nations” and the British were concerned the Palestinian-Arabs were not

a distinct people. In contrast the text included six articles (2, 4, 6, 7, 11 and 22) with obligations for the mandatory power to foster and

support a "national home" for the Jewish people. Moreover, a representative body of the Jewish people, the “Jewish Agency for Israel”, was

recognized.

The Palestinian-Arab leadership repeatedly pressed the British to grant them national and political rights like

representative government. The British made acceptance of the terms of the Mandate a precondition for any change in the constitutional position

of the Palestinian-Arabs. For the Palestinian-Arabs this was unacceptable, as they felt that this would be "self murder". During the whole

interwar period, the British, appealing to the terms of the Mandate, which they had designed themselves, rejected the principle of majority rule

or any other measure that would give a Palestinian-Arab majority control over the government of Palestine.

There was rioting and attacks on and massacres of Jews in Palestine in 1921 and 1929. During the 1930s, Palestinian-Arab

popular discontent with Jewish immigration and increasing Arab landlessness grew. In the late 1920s and early 1930s several factions of

Palestinian society, especially from the younger generation, became impatient with the internecine divisions and ineffectiveness of the

Palestinian elite and engaged in grass-roots anti-British and anti-Zionist activism.

In 1937, the Peel Commission proposed a partition between a small Jewish state, with a proposal to transfer its Arab

population to the neighboring Arab state, and an Arab state to be attached to Jordan. The proposal was rejected by the Arabs. The 2 main Jewish

leaders, Chaim Weizmann and Ben-Gurion had convinced the Zionist Congress to approve equivocally the Peel recommendations as a basis for more

negotiation.

In the wake of the Peel Commission recommendation an armed uprising spread through the country. The Revolt resulted in

the deaths of 5,000 Palestinians and the wounding of 10,000.

The attacks on the Jewish population by Arabs had three lasting effects: First, they led to the formation and development

of Jewish underground militias, primarily the Hagenah ("The Defense"), which were to prove decisive in 1948. Secondly, it became clear that the

two communities could not be reconciled, and the idea of partition was born. Thirdly, the British responded to Arab opposition with the

White Paper of 1939, which severely restricted Jewish land purchase and immigration.[6]

An independent Palestinian state has not exercised full sovereignty over the land in which the Palestinian-Arabs have

lived during the modern era. Palestine was administered by the Ottoman Empire until World War I, and then overseen by the British Mandatory

authorities. Israel was established in parts of Palestine in 1948, and in the wake of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the West Bank was ruled by Jordan,

and the Gaza Strip by Egypt, with both countries continuing to administer these areas until Israel occupied them in the Six-Day

War.[7]

In the 13th century BCE, following their 60-year Exodus from Egypt, the ancestors of today’s Israelis conquered and

took possession of the Land of Israel. This occurred more than 3,000 years Ago. Then, more than 2,000 years ago,

the Israelites were conquered and expelled from their homeland by the Romans. The Romans destroyed their Holy Temple in Jerusalem.

Today, some 2,000 years later, the Israelites have returned home!

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References:

- Bar Kokhba revolt, Microsoft Bing, Accessed 25 August 2024.

- May 14, 1948, Wikipedia, Accessed 25 August 2024.

- The radical ideology at the heart of the anti-Israel protests, David Scharfenberg, Boston Sunday Globe, 25 August 2024.

- Return to Zion, Wikipedia, Accessed 13 September 2024.

- Canaan, Britannica, Accessed 13 September 2024.

- History of the Palestinians, Wikipedia, Accessed 14 September 2024.

- Palestinians: Rise of Palestinian nationalism, Wikipedia, Accessed 14 September 2024.

|

|