| |

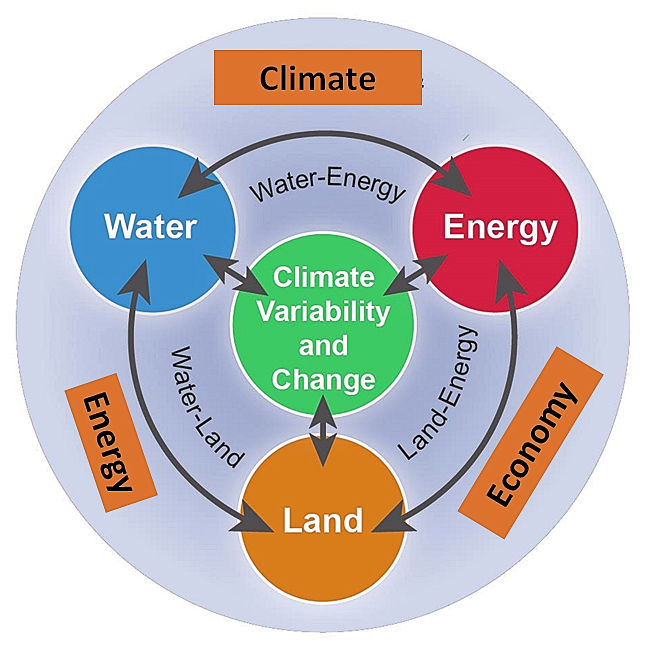

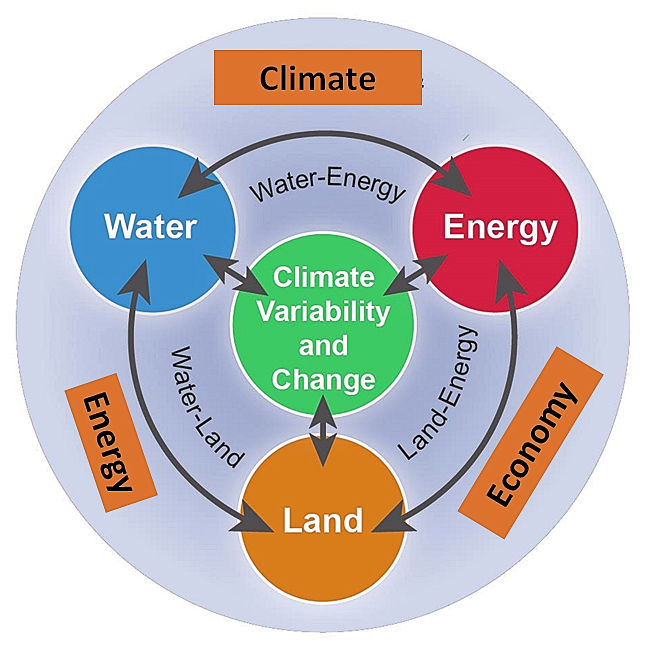

Too many people have tunnel vision. They focus on one thing and exclude other important related

issues from their considerations. Too some, the “climate crisis” is the only issue that matters. To these climate crisis

warriors, the sky is falling and life on earth will cease if we don’t immediately stop polluting the atmosphere with man-made

carbon. To others, we are facing an energy crisis by consuming the earth’s non-renewable energy resources. And to some,

the economy should be the primary focus, since if the economy fails, we will all starve or freeze to death because economic

activity ultimately drives the production of food, energy and all other items required by modern man. In spite of the fervent

claims of each of these zealots, the truth is that all three factors - and others – are important and must be considered in

the aggregate when pursuing public policy and action.

Climate

These days, "supply chain disruptions" has become a euphemism for the effects of climate change.

The disruptions in the supply chain are blamed on numerous influences: the war in the Ukraine, the coronavirus pandemic,

corporate greed and other factors. As of mid-June 2022, the newest major bugaboos in America were the growing fear of runaway

inflation and recession.

There is one school of thought that urges us to forget Ukraine, coronavirus, corporate greed and

“supply chain issues”, when it comes to inflation. This school of thought says that the climate crisis is the real, lasting,

worry, and the one that’s likely to get worse. The Chicken Littles of the world are so focused on climate change that they

fail to account for the other factors that determine the quality of life on planet earth. As a consequence, we have been

allowing the climate crisis to fundamentally alter not just the U.S. but global economies.

The climate change zealots have placed their cause at the head of the line in ways that have forced

choices to be made between the creation of jobs and driving economic growth and protecting the planet.

People fail to realize that while climate change may be an environmental and health issue, it is

battering our economy and the economies of other countries around the world.

Political and monetary policy leaders in this country hinted as much after the US treasury secretary

acknowledged that inflation had reached “unacceptable” highs. It had hit a 40-year high of 8.6% by the end of May 2022 and was

still growing. Later the White House said: “Our hemisphere is facing the devastating impacts and costs of climate

change.”

Assessing the role of climate change on economies is one thing but, to date, most models have merely

assessed the cost of climate-related disasters and have not addressed the underlying effect of climate change on

inflation.

Climate change is largely ignored as an inflationary driver, in part because it manifests itself as

a global problem in ways that makes the direct inflationary impact hard to assess. But climate change and inflation, along

with other economic effects, are intertwined.

Climate change impact is broad and systemic, so there’s no one item in the Consumer Price Index (CPI)

that you can say directly shows the effects of climate change. We can say that grain and gas-oil costs reflect the Ukraine war

but you can’t do that with climate change because it affects so many things.

For example, the loss of timber and homes due to wildfires in the west might show up in housing

construction costs, or the cost of retrofitting homes to guard against coastal erosion and flooding. Right there you have

several things that are either increasing demand or undermining supply - and that’s just one small part of the issue.

Similarly, supply chain issues that are frequently cited as inflationary may not simply be the result

of Covid lockdowns affecting manufacturing, but may be caused by a range of climate change issues that result in roads washing

out or the loss of crops due to extreme weather events and shifting weather patterns.

Climate change, both from weather disaster and commodities costs perspectives appears to be taking an

increasing toll on economies. If one of the inflationary forces is climate, it is one that can’t be tackled simply by

central bankers adjusting interest rates.

Yes, the Covid pandemic and the war in Ukraine impact the economy - inflation being one observable

effect, but the reality is that energy, climate and the economy are all interrelated. When addressing any one of the three,

the other two elements need to be concurrently considered. If all we address are ways to reduce climate change, our energy

needs, along with economic effects – like inflation – will suffer. And we will suffer accordingly. Too many of us have been

framing the climate concern in extremely narrow ways – never a good idea.[1]

Energy

Here in 2022, utilities are warning of potentially serious power outages this summer in many parts

of the country. This crisis isn’t the result of an unforeseeable surge in electricity use; it’s because of misbegotten

policies.

In recent years, many governments have been mandating that utilities use more and more renewable

sources of energy - primarily from windmills and solar panels - to generate power instead of fossil fuels and nuclear plants.

Consequently, many coal- and gas-fired power facilities are being closed. A number of nuclear power plants have been or are in

the process of being decommissioned, and replacements are lagging.

But there is a problem - the technology for the alternative energy sources is costly, and

these alternative energy sources are unable to meet our electricity needs.

Advocates for renewables say they’re needed to fight climate change, but consider the environmental

hazards involved in what it would take to replace our traditional sources of energy. In coming decades, it would require a

1,000% increase in mining to supply the necessary minerals. Ripping up millions of acres for these minerals would impose

horrific environmental costs.

For example, a 100-megawatt natural gas-fired power plant is the size of a typical residential house

and can supply enough electricity for 75,000 homes. Technology experts have pointed out that generating the similar amount of

electricity on a wind farm would require 10 square miles of land, 20 wind turbines - each about the size of the Washington

Monument - 50,000 tons of concrete, 30,000 tons of iron ore and 900 tons of non-recyclable plastic for the blades. Remember

that the energy generated by a wind farm is intermittent – it depends upon whether or not the wind is blowing and how hard.

To store the created electricity for around-the-clock availability would call for 10,000 tons of Tesla-class batteries.

Multiply that farm a few thousandfold, and the costly impracticability of such a total transition becomes clear.

Note that over the last 20 years, $5 trillion has been spent by governments to develop energy

alternatives. Yet the amount of energy supplied worldwide by fossil fuels today has only decreased from 86% to 84%. That’s

$5 trillion for only a 2% change!

Under environmental induced political pressure, American utilities are readying to spend very large

amounts of money on costly and potentially environmentally hazardous energy alternatives. The fact remains that natural gas

is a clean fuel, as even green-minded Europeans now acknowledge, while nuclear power poses no problem with carbon-dioxide

emissions.

Now might be the appropriate time to stand back and re-examine energy, the climate and the economy in

an integrated and unemotional fashion.[2]

When it comes to producing a sustainable and plentiful supply of energy, the U.S. has a huge and

utterly underappreciated advantage over other nations. Here, individuals and companies are allowed to own mineral rights.

In most other countries people can own land, but the government owns and strictly controls any

minerals and natural resources, such as oil, gas, coal, copper, gold, silver and so forth, beneath the surface of someone’s

property. If you discover oil in your backyard, you’re out of luck - it belongs to the government. This has profound

implications that are usually overlooked.

Private ownership of mineral rights in the U.S. means that people and private companies have a strong

incentive to search for minerals. They can profit from the discovery, development and extraction of these natural resources.

This puts a premium on exploration.

The U.S. has major-league oil- and-gas companies, but it also has an enormous and vibrant wildcat

industry. These independents are often more active and nimbler than their giant counterparts. In certain parts of the country,

where the geology may be favorable, private-property owners are free to explore what may be below the surface of their land -

or to sell the leasing rights to others. In that case, if, say, oil is found, the owner would be entitled to royalties.

These individual rights lead to far more exploration. The geology of the southwestern U.S. is no different than that found

across the border in Mexico, yet oil-and-gas exploration in that part of the U.S. is far greater than what is carried out

in Mexico.

Why? Because the oil industry in Mexico is owned by the government. There is no Mexican equivalent

of American wildcatters.

America’s unique approach to mineral rights has kindled an innovative entrepreneurial environment.

Whereas governments elsewhere have strict controls on how minerals are extracted and developed, U.S. companies can try new

ways of doing things.

This freedom to experiment is how drillers developed lateral oil drilling and hydraulic fracturing,

known as fracking, that has skyrocketed U.S. output. Natural gas - a clean fuel once thought to be running out in the U.S. -

became abundant. This led to our energy independence, which is now in jeopardy because of the Biden Administration’s

fossil-fuel antipathy.

Despite the U.S.’ experience, the government-controlled, top-down approach predominates in the rest

of the world. For instance, there’s a huge amount of natural gas waiting to be found and developed in Britain, Europe and

elsewhere. But the governments’ ownership and control of the minerals beneath the surface of the land in these regions of

the world is a costly hindrance to the development of this energy source.[3]

Most recently, the world has been shown to be vulnerable to Vladimir Putin’s control of a large

portion of the world’s supply of oil and gas. The upside to this is that shortages and $8-a-gallon gasoline may force

meaningful investment not just in alternatives like solar and wind but also in pariahs like nuclear and wood.

The global energy crisis in the middle of 2022 could prompt those with the most capital to fast-track

creative solutions and force politicians to get out of the way. That could mean everything from greenlighting new nuclear plant

designs to building better batteries and grids for storing and distributing solar and wind energy. There’s even a place for

quick fixes like burning wood pellets instead of coal.

This would represent a reversal from recent years, during which fossil fuel investment cratered,

Germany and Japan shuttered nuclear plants, and not-in-my-backyard activists blocked hundreds of wind farms in the

U.S. alone.

“This decade is going to be one that is structurally bullish for the energy market. There’s more

discipline today, plus you’re trying to make up for seven years of underinvestment,” said John Arnold, who retired from

active energy trading a decade ago. In recent years, the billionaire philanthropist has put money into solar farms, nuclear

fusion, deep-water oil production platforms and more. He’s been particularly keen to see a regulatory rewrite making it

easier to win approval for energy grids linking urban areas with rural places where wind and solar energy are generated.

“If we really feel like climate change is an existential threat to society, then we need to act like it. You can’t give

everyone a veto on every project.”

The immediate challenge for the West in the middle of 2022 is replacing the Russian natural gas that

powers much of Europe so its factories can keep humming and homes can stay warm next winter. By the end of 2022, the Continent

hopes to replace 2/3 of its prewar Russian imports of 5.4 trillion cubic feet a year. Half of that will come from new imports

of liquefied natural gas (LNG), versus just 20% from renewables. To make LNG, gas is chilled down to –260 degrees Fahrenheit,

turning it into a liquid that can be transported across the ocean in giant insulated tankers. The Europeans are gearing up

to receive LNG on floating regasification facilities.

In March of 2022, President Joe Biden and the European Commission President announced a deal for the

U.S. to send an additional 525 billion cubic feet of LNG to Europe this year and even more in the future. The U.S. can export

more LNG. But it will take time and new capital. The United States went from being the world’s biggest fossil fuel

importer in 2005 to a net exporter thanks to the rapid adoption of fracking.

Europe has shale formations, too, but it never joined the fracking party. As noted earlier, on that

continent, governments, not private landowners, usually retain mineral rights. Politicians had no incentive to fight

antifracking sentiment when they could just buy Russian gas. Now that is no longer an option.

Low-carbon alternatives may be the future, but they face a steep climb against fossil fuels, which

despite a pandemic demand dip, still provide 80% of primary energy worldwide. That’s significant because despite all the

attention paid to alternatives, fossil fuels - gas, oil and coal - still make up 80% of all energy used worldwide,

not much less than two decades ago. One reason is that nuclear power as a share of world energy has not only stopped

growing but has actually shrunk - from 7% to 5% - over that period. After the 2011 disaster at Japan’s Fukushima nuclear plant,

Japan and Germany mothballed nuclear reactors, offsetting nuclear growth in China. In the U.S., new nuclear plants have been

largely stalled since the Three Mile Island accident in 1979.

But the political winds are shifting. California is debating whether to save the Diablo Canyon

reactor, slated for decommissioning in 2025 despite having decades of life left. Japan is slowly bringing some of its reactors

back online. France, with the most nuclear capacity in Western Europe, is moving to reinvigorate its industry – 1/5 of its 56

reactors are currently offline.

Bill Gates of Microsoft fame is a nuclear power booster. He describes nuclear power as the only

carbon-free energy source that can work almost anywhere 24 hours a day. In 2008 he cofounded a company which has developed

(in concert with GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy) the Natrium reactor - a fast reactor fueled with low-enriched uranium that sits

in a meltdown-proof pond of molten salt, which doubles as long-term energy storage. In 2018, amid rising tensions with China,

the U.S. government scuttled the company’s plan to build its first Natrium reactor in China. But now the Department of

Energy has agreed to provide up to $2 billion - roughly half the cost - to build the first commercial-scale Natrium reactor in

Wyoming at the site of a retiring coal-fired generator.

Others share Gates’ enthusiasm. Westinghouse is now completing two new AP1000 reactors in Georgia

and has four on order from China (it has already built four there), plus a six-reactor deal in Poland.

In 2021, wind generation grew 12% and solar 21% worldwide. That’s not fast enough. But there are some

promising developments, including breakthroughs in battery technology crucial to storing intermittently generated solar and

wind power. Yet battery makers face global shortages of copper, nickel and lithium.

When it comes to alternatives, “Perfect is the enemy of the good.” One short term environmental

initiative is carbon sequestration. Another is wood pellets. Enviva, the world’s biggest wood pellet company, has 10 wood

pellet plants in 6 southeastern U.S. states. These plants take trees and scraps from sustainable forestry operations and

press them into 6,000,000 tons a year of 3-inch-long pellets, which are shipped to customers in the United Kingdom and Japan.

These pellets are then burned in power plants instead of coal. It’s said that “the Southeast U.S. is the Saudi Arabia of wood”.

Enviva says they can double pellet output by 2027. Environmentalists have qualms, but wood pellets are seen by some as a smart

short-term fix.

There’s another natural short-term “fix”: As Russian non-renewable energy disappears from the market,

prices will surge until the global economy slows down enough to reduce demand. In time, the problem will be solved, but not

without short-term pain and massive investment - especially in non-fossil fuels. The International Energy Agency (IEA)

estimates that the world needs to double its current spending on alternative energy and invest a total of $12 trillion by

2030 to have any chance of holding global warming to 5 deg., Fahrenheit.

Still, there’s room for optimism, if we adopt an all-of-the-above approach to alternatives and don’t

let excessive government regulation and NIMBY naysayers stand in the way. Over the long term, society has historically done a

great job of delivering ever cheaper energy.[4]

The push to replace fossil fuels with renewable energy has been stalling in recent years. In these

United States, big solar projects are facing major delays. Plans to adapt the grid to clean energy are confronting mountains

of red tape. Affordable electric vehicles are in short supply.

The United States is struggling to squeeze opportunity out of an energy crisis that should have been

a catalyst for cleaner, domestically produced power. After decades of putting the climate on the back burner, the country is

finding itself unprepared to seize the moment and is at risk of emerging from the crisis even more reliant on fossil

fuels.

The problem is not entirely unique to the United States. Across the globe, climate leaders are

warning that energy shortages prompted by Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine and high gas prices driven by inflation

threaten to make the energy transition an afterthought.

In response to gas prices climbing to record-highs there has been a call to be pumping oil like crazy

and to be moving into long-term (fossil fuel) infrastructure building.

In the United States - the world’s second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases after China - the

hurdles go beyond the supply chain crunch and sanctions linked to the war in Ukraine. The country’s lofty goals for all

carbon pollution to be gone from the electricity sector by 2035 and for half the cars sold to be electric by 2030 are

jeopardized by years of neglect of the electrical grid, regulatory hurdles that have set projects back years, and failures

by Congress and policymakers to plan ahead.

The push to eliminate or significantly reduce carbon emissions into the atmosphere is further

countered by plans to build costly new infrastructure for drilling and exporting natural gas that will make it even harder

to transition away from fossil fuels. In the U.S., Congress is barely talking about clean energy.

Lawmakers have balked for more than a decade at making most of the fundamental economic and policy

changes that experts widely agree are crucial to an orderly and accelerated energy transition. The United States does not

have a tax on carbon, nor a national cap-and-trade program that would reorient markets toward lowering emissions.

The effects of the U.S. government’s halting approach were being felt by solar-panel installers,

who saw the number of projects in a recent quarter fall to the lowest level since the coronavirus pandemic began. There was

24% less solar installed in the first quarter of 2022 than in the same quarter of 2021.

The holdup largely stemmed from a Commerce Department investigation into alleged tariff-dodging by

Chinese manufacturers. Faced with the potential for steep retroactive penalties, hundreds of industrial-scale solar projects

were frozen in early April of 2022. Weak federal policies to encourage investment in solar manufacturing left American

companies ill-equipped to fill the void.

Meanwhile, adding clean electricity to the power grid had become an increasingly complicated

undertaking, given the failure to plan for adequate transmission lines and long delays connecting viable wind and solar

projects to the electricity network.

Also, remember that in 2021, only 4 percent of vehicles sold in the United States were

electric.

While the United States was hitting some significant benchmarks in the transition to greener

electricity, boasting record installations of clean power in the first quarter of 2022, the rate of growth had slowed and

fallen behind where it needs to be to reach key climate goals. America is not alone in this predicament.

The record growth in wind and solar power generation in 2021 was outpaced by the world’s

rising demand for energy. Clean power could meet only a third of that growth in demand. The rest was largely met

by burning more coal. The transition to clean energy sources is not fast enough and this movement is not resilient enough

to the increased volatility in the current economic and political environment. For example, the United States needs to triple

its pace of emissions reductions to meet the targets it had set for itself.

There are numerous hurdles in the way, as outdated federal rules and local planning disputes slow

projects down. In November, for instance, one of the country’s larger clean-energy projects faltered in the Northeast. Maine

voters stymied plans for a transmission line that would bring enough clean electricity from hydroelectric plants fueled by

dams in Canada to power 900,000 homes in New England.

This setback is indicative of a much bigger nationwide challenge in building transmission lines for

all forms of clean energy. The Department of Energy (DOE) reported that transmission systems need to be expanded by 60% by

2030 to meet the administration’s goals. And they may need to triple in capacity by 2050.

Patching wind and solar projects into a grid infrastructure that does exist is increasingly

challenging. Over the last decade, the time it takes to get a project online has jumped from 2 years to longer than

3-1/2 years. Grid operators are taking longer to study project viability and are overwhelmed by a dramatic rise in the

number of projects in the queue.

While the Biden administration has promised to ease congestion and shore up the grid through billions

of dollars in spending on transmission lines and other improvements authorized in the infrastructure package that Congress

passed, it will probably be years before the upgrades and expansions are operational.

Clean-power producers are also hitting numerous barriers in their bid to generate huge volumes of

energy with offshore wind turbines. Among them is a provision in the House bill funding the Coast Guard mandating that only

American ships can be involved in construction work on the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf. Amid a shortage of such American

ships and trained crews to operate them, wind energy developers warn, the measure would effectively halt production of

offshore wind.

As the clean-electricity industry confronts these growing pains, promoters of electric cars are

running into their own obstacles. Government programs that exist to promote zero-emissions vehicle production are sending

mixed signals to manufacturers and drivers as some tax credits expire. Congress has delayed extending them. The United States

and other countries need to dramatically step-up electric vehicle production to meet their goal of making all transportation

carbon-neutral by 2050. Meeting this goal would require zero-emission cars and trucks to make up 61% of all vehicles sold

worldwide by 2030. As previously noted, only 4% of cars sold in the United States last year were electric vehicles.

The sticker price of a new electric vehicle is $10,000 more than a comparable gas-powered model,

and lawmakers have so far balked at renewing some of the subsidies designed to bring the price down. Even so, interest in

the vehicles is high enough that many buyers eager to get an electric car or hybrid have found themselves instead on a

waitlist.[5]

Energy, the economy and protection of the environment have to all be jointly considered when taking

action on any one issue is concerned. Addressing one issue while ignoring the other interrelated ones could produce severe

unintended consequences. In response to the rapidly escalating gasoline prices in the early summer of 2022, President Biden

asked the leaders of seven U.S. oil companies to do something - anything - to lower the price of gas and help American

consumers. However, one energy expert said that if the president’s request/plan did anything at all, it might well

backfire.

In his message to the oil company leaders, Biden asked them to plan to meet with the U.S. Secretary

of Energy and provide an explanation as to why oil refineries in the U.S. were not running at full, pre-coronavirus pandemic

capacity.

The energy expert said that Biden’s plea might not have the intended impact at the pump. It could

cool already frightened markets. It could have a countering effect by making companies less willing to invest in new

refineries and could be counterproductive over the longer term – a decidedly unintended negative effect.

In any case, refineries in the United States were not necessarily the issue. Given how profitable it

was to operate a refinery in 2022, everyone who could operate a refinery at full capacity was already doing so.

The energy expert stated that one thing Biden could do was to convince a country like Saudi Arabia

to increase its production. Saudi Arabia was one of the few countries that had the capacity to increase oil production. If

the President were able to convince the Saudi leadership to use their spare production capacity more aggressively, that

really could lower prices.

So what else could bring the price of gas down? Mainly, time, according to the expert.

Refineries generally do their maintenance in the spring. So, refineries coming out of maintenance,

some new ones possibly coming online, and some easing of refinery restrictions in China, could help ease the refinery portion

of the price of gas.

The price of gasoline at the pump is the result of three factors: the price of crude, the price of

refining, and taxation.

In mid-2022, the world’s markets were reeling from sanctions placed on the Russian oil market.

That meant that Russia has had to look for - and it found, in India - a new market to sell their oil. Russia was the world’s

second largest exporter of refined petroleum product, and that gasoline had to go somewhere. That meant that the supply chain

issues caused by the market shift - Russian gasoline to India instead of Europe – would eventually settle, as that petroleum

reentered the worldwide market.[6]

The Economy

By mid-2022, the economy in the United States was showing strain as high prices and rising inflation

continued to punish the average citizen. The following gives a snapshot of how the U.S. economy was doing. Economists call the

factors described leading economic indicators because they measure the early influencers on growth.

The unemployment rate in the U.S. remained low. It decreased in early 2022 following high

job losses in 2020. The unemployment rate was 3.6% in May 2022. That number is similar to before the pandemic and is the same

as it was in March and April. The economy added 390,000 jobs in May 2022, far above economists' expectations.

Real gross domestic product (GDP), often touted as a measure of the overall economy, fell

1.5% in the first quarter of 2022. The gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate was 1.5% for the first quarter of 2022. When

it's below 2%, then the economy is in danger of contraction.

Orders for durable goods like machinery and equipment increased 6.8% in the first quarter

of 2022, while nondurable goods (pharmaceuticals, food, and lodging) fell by 3.7%.

In May of 2022, interest rates increased, this time by 0.50%.

The consumer price index (CPI) for all items rose 1.0% in May 2022. Over the last twelve

months, prices on all items increased by 8.6%.

The stock market showed strain as the S&P 500 and Nasdaq dipped significantly in January of

2022. Both indexes were low and erratic into March before regaining ground in April. In June the S&P 500 dipped into a bear

market, 20% below its recent peak.

The stock market tells what investors think the economy will do. The stock market recovered

surprisingly well after the pandemic, with the S&P 500 continuously hitting new highs between October 2020 and December

2021.

In November, 2021, the Dow hit a record high. It hit another high in early January, 2022, when it

closed at 36,800. The Nasdaq Composite and S&P 500 were also climbing throughout 2021, before dipping into a correction in

January 2022.

In early 2022, all three indexes started to drop, though they were still above where they were in

January 2021. In March, as the global economy was affected by Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the market dipped further before

regaining momentum. In June of 2022, rising inflation and expectations of a sharp Fed response pushed the S&P 500 into

bear market territory, a 20% loss off its most recent peak.

The inflation rate, as measured by the CPI, was 8.6% year over year in May 2022, up

significantly. The Fed has been increasing interest rates since March 2022 in order to bring down inflation. A 2% inflation

rate is considered healthy because consumers expect prices to rise. That makes them more likely to buy now rather than wait.

The increased demand spurs economic growth.[7]

So, here in the second half of 2022, we continue to face the three major concerns of energy,

the climate and the economy. My message – once again – is that these issues are intimately interrelated and

must be addressed together in order to avoid unintended consequences that could be highly detrimental and significant if

addressed independently.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References:

- Climate crisis is ‘battering our economy’ and driving inflation, new book says, Edward Helmore,

The Guardian,

12 June 2022.

- Coming Summer Outages Were Avoidable, Steve Forbes, Forbes: Pge 15,

June/July 2022.

- U.S.’ Unique Energy Advantages, Steve Forbes, Forbes: Pges 15-16,

June/July 2022.

- OVER A BARREL, Charles Helman, Forbes: Pges 102-108, June/July 2022.

- Why an energy crisis and $5 gas aren’t spurring a green revolution, Evan Halper,

The Washington Post,

14 June 2022.

- BIDEN’S BEG FOR BIG OIL TO LOWER PRICES COULD BE A SLIPPERY SLOPE,

Matthew Medsger,

Boston Herald: Pge 7, 16 June 2022.

- How Is the U.S. Economy Doing?, Kimberly Amadeo, the balance,

30 June 2022.

|

|