Getting a Valve Job – 2017 Style

© David Burton 2017

Getting a Valve Job – 2017 Style |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

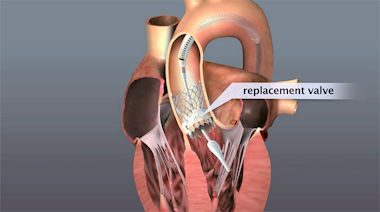

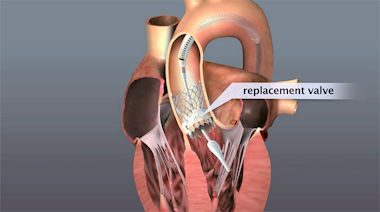

My first valve job was performed on a 1951 Plymouth which had an L-head or flat-head 6-cylinder engine. The engine compartment was relatively spacious and uncluttered. The engine head lifted off easily after removing items attached to it such as the carburetor. This exposed the top of the engine block along with the valves and their seats. Access to the engine’s valve stems, springs, retainers, etc. was achieved by removing a valve cover plate on the side of the engine block. Care had to be taken so as not to allow small items such as the retainers, to fall down into the holes in the valve compartment that connected the valves to the camshaft. As part of my education in performing engine valve replacement and auto maintenance and repair in general, I became intimately familiar with the Prospect Street and Webster Avenue area in Cambridge, along with the Everett Avenue and Second Street area in Chelsea in Massachusetts. These were where nearby auto junk yards, second hand auto parts, machine shops, and auto parts stores were located. I also added to my education by acquiring repair and manufacturers’ maintenance/repair manuals for the cars owned and through the purchase of appropriate Chilton’s Auto Repair books and Motor's Auto Repair Manuals, the bibles for do-it-yourself auto repairmen. Over time, I purchased a substantial collection of tools (mostly Craftsman) and test equipment needed to work on cars of mid to late 20th century vintage. Recently, I was involved in a different type of valve job – the replacement of the aortic valve in my heart. The procedure was carried out at Tufts Medical Center (TMC), a teaching hospital in Boston. I did not personally perform this particular valve job. The aortic valve is located between the left ventricle and the aorta. When the left ventricle of the heart contracts, pressure rises in the left ventricle. When the pressure there rises above the pressure in the aorta, the aortic valve opens, allowing blood to exit the left ventricle into the aorta. When ventricular contraction ends, pressure in the left ventricle rapidly drops and the blood pressure in the aorta forces the aortic valve to close. The aortic valve normally has three cusps or leaflets, which, with age, may calcify, resulting in incomplete opening and/or closure. Calcification, also called stenosis, of the aortic valve causes leakage around the valve, which can be detected as a “heart murmur” and a symptom of which may be shortness of breath. Oxygenated blood from the lungs is brought to the heart's left atrium through the pulmonary vein. Then it passes through the mitral valve and into the left ventricle. With each of the heart muscle’s contractions, the oxygenated blood exits the heart from the left ventricle through the aortic valve and into the aorta, which is the body’s main artery. It distributes oxygenated blood to all parts of the body. The aorta originates at the left ventricle of the heart and extends down to the abdomen, where it splits into two smaller arteries. For several years, Dr. Spector, my primary care physician (PCP) had noted a slight “heart murmur” which he ascribed to aging of my aortic heart valve. Over the years, occasional echocardiograms confirmed the diagnosis and, at the same time, did not indicate the need for any immediate remedial action. In early January of this year, during my annual checkup, Dr. Spector told me that my “heart murmur” was more pronounced and suggested that I have another echocardiogram (which I had at the end of the month) and he arranged for me to see a cardiologist, Dr. Wells. Since I was going to be in Israel during the month of February, I asked to have my appointment with Dr. Welles after I returned. The appointment ended up taking place toward the end of April. For the past decade, I had been travelling to Israel each winter for 2- to 8-week volunteer work, sightseeing and education. These visits to Israel required a considerable amount of walking, hiking, climbing and other activities involving moderate physical exertion. During this year’s month-long time in Israel in February, I noticed that I was experiencing shortness of breath after some of the physical activities. Upon returning from my Israel trip, I met with my cardiologist who suggested that I consider aortic valve replacement and arranged for a meeting with Dr. Rastegar, a Cardiac Surgeon. Dr. Rastegar agreed with the cardiologist’s evaluation and recommended that I have the valve replacement performed with a procedure known as transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). Following the visits with Dr. Wells and Dr. Rastegar, I boned up on what was involved in aortic heart valve replacement and particularly on transcatheter aortic valve replacement. I learned that TAVR is a “minimally invasive” surgical procedure that repairs the valve without removing the old, damaged valve. Instead, it wedges a replacement valve into the aortic valve’s place. Similar in many ways to a stent placed in an artery, the TAVR procedure threads a fully collapsible replacement valve to the valve site in the heart through a catheter that is usually inserted through the femoral artery in the groin. Once the new valve is expanded at the site of the old aortic valve, it pushes the old three leaflets of the valve out of the way and the cow tissue in the replacement valve takes over the job of regulating blood flow. The older and more “conventional” procedure to replace an aortic valve is typically an open-heart surgery wherein the damaged valve is removed and replaced with an artificial valve, frequently with a heart valve from a pig. During open-heart valve surgery, the doctor makes a large incision in the chest. Blood is circulated outside of the body through a machine to add oxygen to it (cardiopulmonary bypass or heart-lung machine). The heart may be cooled to slow or stop the heartbeat so that the heart is protected from damage while surgery is done to replace the valve with an artificial valve. This type of surgery likely requires an initial recovery period of several weeks, with complete recovery requiring 4 to 12 weeks. In some cases, full recovery may take several months. The TAVR procedure is fairly new – having been first used in Europe about a decade earlier. The older “conventional” valve replacement procedure requires an open-heart procedure with a “sternotomy”, in which the chest is cut open to provide access to the heart and the aortic valve. The recovery from this sternotomy is long and painful, as opposed to the TAVR where recovery is rapid – usually only 2 or 3 days in the hospital – and quite painless. Since there wasn’t any urgency to having the valve replaced, I asked to have the TAVR procedure performed in late July because of commitments that I had during June and the first half of July, including a wedding in Maine in early July. An immediate and ongoing complication cropped up – The nurses’ union at Tufts Medical Center was threatening to go out on strike because ongoing negotiations between TMC management and the nurses’ union had failed to produce a new labor contract. If carried out, the strike at TMC would be Boston’s first nurses strike in more than 30 years — a possibility that was costing the hospital $1 million in preparations. The hospital and the nurses’ union had been trying to negotiate a new contract since April 2016, more than a year previous. The threat of a strike continued through May and June and into early July. On Thursday, 6 July, a week prior to my scheduled heart valve replacement, the nurses’ union rejected a “final” contract offer from Tufts Medical Center and threatened to conduct a one-day strike on Wednesday, 12 July - as it turned out, two days before my scheduled procedure. At the same time, Tufts Medical Center said they would lock out the unionized nurses for four days if they went on strike and replace them with substitute temporary nurses over that period of time. While all this was taking place, the process of getting ready for my valve replacement continued. Dr. Wells arranged for me to have a cardiac catheterization procedure at the beginning of May. Cardiac catheterization is utilized to examine how well the heart is working. A catheter is inserted into a large blood vessel – in my case an artery in my wrist - that leads to the heart. During the procedure, the pressure and blood flow in the heart is measured. A video screen monitors the position of the catheter as it is threaded through the major blood vessels and to the heart. Coronary angiography is done during cardiac catheterization. A contrast dye, visible in X-rays, is injected through the catheter after which real-time X-ray images show the dye as it flows through the heart arteries. This shows if there are any arteries that are blocked or restricted. It also allows measurement of the pressure of blood in each heart chamber and in blood vessels connected to the heart, and a view the interior of blood vessels. The catheterization process itself took about an hour and was entirely painless. I was awake throughout and could view some of the monitoring displays while the catheterization was taking place. Preparation time and time spent in the recovery room after the procedure to ensure no subsequent problems, e.g., bleeding at the catheter insertion site or adverse reaction to the contrast dye, amounted to another 3 hours. The cardiac catheterization procedure confirmed that I was a good candidate for the TAVR. Shortly after the cardiac catheterization, I met with Dr. Weintraub, who specializes in the TAVR procedure at TMC, to review what the procedure would involve and to set up a tentative date for the procedure. The first opening was the morning of August 4th, which met my requirement to have the procedure no earlier than mid-July. I also favored the morning surgery rather than the afternoon because it meant the least time without food or water and a possible earlier discharge after the surgery. The next step was to have blood drawn to make sure there were no problems in that area – there were none. Next, in early June, I had another echocardiogram, which confirmed the results of the previous echocardiogram taken in early January. Following the blood work, I underwent a full pre-op battery of testing and procedures toward the end of June. Included in the TAVR pre-op tests were the following:

On July 7th, I received a call from the Nurse Practitioner (NP) in the TMC cardiac surgery department, confirming my TAVR date of 14 July in the morning. She reminded me of the steps I needed to take prior to the procedure and asked if I had any questions. In light of the pending strike, I asked if she was going to participate in my procedure. She told me that she was scheduled for vacation that week and that earlier contract impasses had previously been resolved at the last minute. Tufts Medical nurses were just hours from striking in 2011 when both sides agreed to a last-minute deal. The NP said that I would be contacted by Dr. Weintraub early the next week to further discuss the situation. On Monday afternoon, 10 July, Dr. Weintraub called to say that in spite of the threatened nurses’ strike and the threat of a 4-day nurses lockout, it was tentatively planned that there would be business as usual at the hospital. He explained that plans were in place to staff with replacement nurses and asked how I felt about proceeding with the surgery if the strike and lockout happened. I told him that if he and Dr. Rastegar were comfortable with the nursing replacements, that I had had no problem with proceeding. Dr. Weintraub said that the final decision was up to Dr. Rastegar, and, assuming his go-ahead, the TAVR procedure would go on, as scheduled on the 14th in the morning. Well, negotiations broke down and the TMC nurses went out on strike on at 7:00 am on Wednesday (12 July). The one-day strike lasted until 7:00 am on Thursday (13 July) when the nurses were prepared to return to work. However, the hospital had contracted with replacement nurses for five days of work and locked out the nurses who had gone out on strike for four additional days, i.e. until 7:00 am on Monday (17 July). This meant that my TAVR team would have replacement nurses in the surgery room rather than the TMC nurses who were experienced in performing the TAVR procedure in concert with Doctors Rastegar and Weintraub. If that was acceptable to Doctors Rastegar and Weintraub and to Tufts Medical Center, it was OK with me. Starting on Sunday, 9 July, as per instructions, I stopped taking some of my usual medications in preparation for the hospital visit later that week. I had my last food prior to the TAVR procedure late Thursday (13 July), a shower with special antiseptic soap around 4:00 a.m. on the morning of the procedure (14 July) and also a special mouthwash after brushing my teeth that morning. We (my wife and I) left for the hospital by Taxi around 5:15 a.m. and checked into cardiac surgery unit around 6:00 a.m. Because of the nurses lockout, we entered the cardiac surgical building through a rear door which had security guards on duty. Picketing nurses were at the main entrance, and security was in place at all doors to TMC. From check-in until entering the surgery room, various members of the TAVR team stopped in to explain what would be taking place, to assure me that the team was an excellent one, to answer any questions about what would be happening, to explain the risks and to reaffirm that the risk levels were low but finite, and to reiterate that the TAVR procedure had been performed at Tufts Medical Center for hundreds of times with a history of excellent outcomes. Around 8:00 a.m., I was wheeled into the cardiac surgery / TAVR room. It was huge, all white and filled with an enormous amount of modern-looking equipment and digital displays. I estimate that the TAVR/Cardio team consisted of about a dozen people, although I didn’t get a chance to see them all. Starting around 10:00 a.m., my TAVR procedure was performed by Dr. Weintraub, with Dr. Rastegar assisting. Dr. Rastegar was also on standby in the operating room in case a problem arose which would require reverting to the older open-heart surgery that meant a sternotomy. The procedure was completed around 12:00 noon, after which I was taken to the Cardiac Care Unit (CCU) which is the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for cardiac surgery patients. I woke up in the Cardiac Care Unit (CCU) around 1:00 p.m. Waking up, I felt the urge to urinate, but knew that I already had a Foley catheter installed. Also, I had a sore throat and the need to cough. An oxygen mask covered my nose and mouth and I frequently lifted it to breath in some fresh air. I simply don’t like anything covering my nose and mouth. I was hooked up to a number of digital displays, with a blood pressure (BP) cuff on my right arm and intravenous lines into both my right and left arms. My wife and younger daughter were in the room and were shortly joined by my older daughter. I had a sip of ice water to help with the sore throat, tried to cough up some mucus, and started complaining about the pain from the Foley catheter. The sore throat, coughing and Foley catheter complaining continued till late in the afternoon when I convinced them to remove the catheter. To combat the sore throat, I sucked on some throat lozenge’s. I had no chest pains and no pains in the groin at the catheter insertion sights. Both my BP and my blood sugar readings were high. My blood sugar level always goes up after surgery, but never to seriously high levels. A shot or two of insulin always took care of the problem. I had also discontinued my diabetes med’s the week prior to the surgery. The high BP was another story. Because of the Foley catheter problem, I continually tensed and tightened up causing my systolic BP reading (the high number in one’s BP reading) to run up around 180 – it’s normally around 120. As soon as the Foley catheter was removed, my systolic BP readings dropped to normal. By 5:00 p.m., I was almost feeling normal and ready to go home. The sore throat would continue for another day or two along with the cough which lessened in severity as time went on. Dr. Weintraub stopped in for a short visit and assured me that the TAVR procedure had gone very well and all appeared to be normal. I got a light hospital dinner around 6:00 p.m. – quite good – after which I settled in for the evening. The Red Sox and Yankees were playing that evening; I had the CCU room to myself; and a TV monitor on the wall in front of my bed. Although the TV reception left something to be desired, it was adequate for my needs. The Stryker bed was too short and not very comfortable, but I made do. Although the regular TMC nurses were locked out, the replacement nurses did a great job throughout my short hospital stay. Care was excellent and, if I didn’t know about the strike and lockout, I wouldn’t have known anything was going on. The Red Sox defeated the Yankees, after which I intermittently watched TV and tried to sleep a bit. Sleep in a the CCU was difficult because of the continuous noise throughout the night – bells, buzzers, beeps, and the night shift CCU team talking at their centralized monitoring stations. On top of all that, I was hooked up with wires and tubes to the monitoring equipment in an uncomfortable bed. Typically, I would nod off for half an hour and then wake up for 15 minutes throughout the night. The next day, Saturday, went very well. I enjoyed an egg foo young omelet for breakfast. Later, I asked if I had received any sutures where the groin incision for the TAVR catheter insertion was located. I was told that no stitches were used and, instead, the incision was closed with a medical version of super glue. I was doing well enough that I could get out of the bed and start walking. This required that someone from physical therapy (PT) be called to make sure I didn’t fall and injure myself. The call to PT was made several times. At first PT said they didn’t have anyone available. I suggested that the on-duty nurse in CCU could get me out of the bed, but they didn’t want to do this. I offered to disconnect my monitoring lines and tubes and get out of bed myself, but again my suggestion was ignored. Finally, after about 4 hours of constant complaining and badgering, PT arrived and I was released from the bed and escorted around the CCU twice. Returning to my CCU room, I sat on a chair (with my monitoring lines and tubes reattached) instead of getting back into bed. Normally, I would have been moved from the CCU to a regular hospital room on Saturday, but all rooms in the hospital were full. So, I remained in the CCU, which was fine with me - I and the CCU staff were now familiar and comfortable with each other. The Red Sox and the Yankees were scheduled for a day-night double-header, with the first game beginning at 1:00 p.m. I had a light lunch – again, quite good – and then went through an afternoon of an occasional blood drawing, blood-glucose testing, the occasional shot for this or that, inspections of my groin area to make sure there was no infection, an echocardiogram, an electrocardiogram, and the occasional stethoscope checking of my heart and lungs. I was doing so well that the CCU physician said that unless something changed, I could be discharged the next day. As it turned out, the first game of the Red Sox-Yankees doubleheader went 16 innings and wasn’t over until 7:00 p.m. I had dinner at 6:00 p.m. – another good meal - and then spent the evening in a manner similar to that of the afternoon - the night half of the doubleheader on TV, with continuous checking of my condition, which was now nearly normal. One blood drawing at night broke up the monotony. The lines in my arms had essentially dried up so it was necessary to draw blood from a fresh site. It took three attempts to hit a vein and get the needed blood. This left some new black and blue marks to add to those already present on my arms on my stomach. On Sunday morning, around 7:15 a.m., the physician on duty in the CCU came to check on me. All was normal and he said he would begin filling out my discharge papers. The process of discharging me from the hospital however took until 3:15 p.m., some 8 hours. There were two main reasons for the inordinately long discharge process: 1) nearly all patients are discharged from a hospital room, not the CCU, so the CCU staff were not familiar with the process and, 2) this was a Sunday and not all hospital offices were fully staffed. Upon discharge, I received instructions and a prescription for Plavix, an anti-clotting medication, that I would need to take for the next 6 months. On the next two days, Monday and Tuesday I received calls from my Primary Care Physician, the TAVR surgeon’s office and from the Nurse Practitioner in the TAVR surgeon’s office, all checking on my well-being, asking if there was anything I needed and confirming the scheduling of my follow-up visits. I was released from Tufts Medical Center just two days after my heart valve replacement. I kept my physical activities to a moderate level for the rest of the week and avoided driving until Saturday, later in the week. My major reminders of the valve replacement were: a stiff neck, which I assume resulted from my head being turned sidewise while I was under anesthesia and a while a breathing tube was inserted, along with numerous black and blue marks from all the needle sticks and IV lines. After a day or two of neck-stretching exercises, the stiff neck pains subsided. A week later, the black and blue marks were fading but some still remained as a reminder of the procedure. On Friday, 21 July, a week following the valve replacement, I was examined by my PCP, Dr. Spector, to ensure that there were no complications – there were none. A month after the TAVR, On 17 August, I returned to TMC for an echocardiogram and a follow-up visit with Dr. Weintraub to get an all clear. I was given an “All Clear” of sorts. I would be on a blood thinner for the next 5 months – I already had a plethora of red, blue and purple marks in various places where a simple bump had resulted in bleeding under the skin and ordinarily minor scratches took forever to stop bleeding. I reverted to an old time-tested solution to stop this minor bleeding – a styptic pencil which I had discovered ages ago when I had first started shaving the old-fashioned way - with razor blades. I also began to wear a medical alert bracelet to warn that I was on a blood thinner should a major bleeding accident occur. I was advised to attend a local outpatient cardiac rehabilitation program at a conveniently located nearby facility. My next visit with Dr. Weintraub wasn’t to take place until 12 months after the surgery. Following my visit with Dr. Weintraub, I made an appointment with my cardiologist in order to set up a regular schedule of visits to monitor the ongoing status of my heart. I also arranged to start a program of cardiac rehabilitation at the Cardiovascular Disease Prevention Center at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) that would last about 2-1/2 months, beginning in mid-September of 2017. My 2017 valve job turned out be quite different than my prior experience with other valve jobs. The cost difference was quite pronounced – back in the early 60’s, a typical valve job might cost around $100; the most recent cost summary of my valve job, through August 14, 2017, amounted to over $222,000, with more (such as my rehabilitation program) to come. The outcomes however, were somewhat similar, in that the machines in which the two different type of valves were located continued to run after the valve jobs – both, better than prior to the procedures. |

| 31 August 2017 {Article 304; Undecided_57} |