| |

The American government, like most governments around the world, engages in what is

called “industrial policy-making”. In socialist countries, such involvement is frequently all-embracing, and the

notable failures of socialistic regimes attest to the superiority of democratic capitalistic economic systems over

totalitarian socialistic systems. But even in highly capitalistic systems, some government involvement may be

beneficial. It is highly likely that such interference can never be totally eliminated, nor is it desirable that a

total hands-off policy should be implemented. Having said all that, let’s look at some recent U.S. government

involvements in industrial policy-making that has not turned out well and at some current and pending industrial

policy-making that also may not be particularly wise.

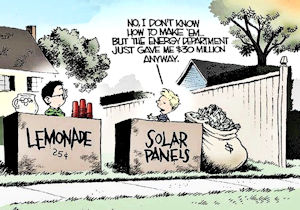

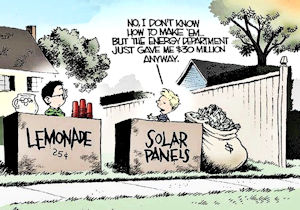

As an example of past government industrial policy that turned out to be misguided and a

waste of taxpayer’s money, consider the U.S. government’s financial support of the failed solar company Solyndra.

This government involvement “is often held up as the kind of thing that occurs when the government picks

winners.” (Ref. 1) Many would argue that the government simply is

unqualified to steer innovation and that the “market” does a much better job of determining innovation winners. On

the other hand, there is a quite valid argument that government should have a hand in steering innovation in order

to derive benefits for the common good that may be less attractive financially to the marketplace. For example,

protecting the environment may be a valid government objective that may not be as attractive to investors as some

polluting but profitable thingamajig.

Government involvement may be for reasons less noble than protecting the environment. It may

be for political advantage, for national boasting rights, or for just plain bull-headedness and ignorance.

Industrial policies like that “have given birth to such white elephants as the Concorde, a plane meant to bolster

the aerospace industry in the U.K. and France.” (Ref. 1) The

Concorde supersonic transport was “a beautiful plane meant to showcase British and French aerospace industries

whose every flight lost money.” (Ref. 2) In that regard, the

Concorde was a financial failure but a national success. Who was right and who was wrong?

In the case of Solyndra, the outcome was bad for everyone. “{M}oney was lent to Solyndra

for political reasons – President Obama and his administration used the company as a high-profile way to highlight

its green-energy initiatives. Having singled out the solar company for praise, the administration was then reluctant

to end its commitment.” (Ref. 1)

Government industrial policy-making frequently fails because of a lack of focus.

Successful capitalists, on the other hand, are almost maniacally focused on one clearly defined objective. All too

often government policy tries to achieve multiple objectives, with many fingers in the pie, some pulling in very

different directions. On top of that, there is often no one in control - direction and oversight coming from a

committee rather than a leader.

In 2009, the Obama administration passed the $787 billion stimulus package that included

$60 billion for energy projects and research. “But from the start, the energy spending was headed for trouble because

it tried to serve multiple purposes: {i.e. it lacked focus} provide a monetary boost, create jobs, and seed the

beginning of a green-energy infrastructure. {It was} pork barrel politics. . . .

“The problem was that these objectives often conflicted. : . . . investments were made

to help economically stressed regions even if they weren’t the wisest choices for building an energy sector. {But

they were wise choices for getting voter support.} government investments were made in a number of large battery

production facilities in Michigan, each one coming with a promise to boost the local economy, even though there

was not yet nearly enough demand for the batteries. Among the outcomes of the stimulus investments, not

surprisingly, were the bankruptcies of Solyndra and other battery startups.

“The stimulus energy investments were {to put it very mildly} 'a bit of a disaster'.

. . . Not only did the government make large bets on a few companies, in effect picking winners, but it did so

without clear rules and criteria for their choices. And . . . ‘the selection of the battery and solar companies

was extremely opaque. A lot of it seemingly came down to if you had a former assistant secretary of energy

doing the lobbying for you.’ [Emphasis mine]

“. . . ‘experience tells us there are more misses than hits’ with such government

interventions.” (Ref. 1) “{T}he failures of President Obama’s

stimulus bill, including the bankruptcies of favored companies like the solar-panel manufacturere Solyndra, have

shown how hard it is to get industrial policy right.” (Ref. 2)

Some have viewed the Solyndra debacle as more than just a bad policy decision. Some have

seen it as just plain political corruption. “When government tries to pick winners and losers, the inevitable

consequence is corruption. Yes, corruption. If not in a legal sense, certainly in a moral sense.

“. . . Something obviously smells rotten when $500 million in loan guarantees go to a

single business with clear political connections. That would be scandalous under any circumstances, but when a

bankrupt government underwrites a bankrupt business with dollars it doesn’t really have, it is really

scandalous.

- - -

“At the end of the day, it is about the corruption that will always happen when government

tries to bolster one industry, penalize another, or ‘stimulate’ one sort of economic activity over another. If

politicians are allowed to pick winners and losers, a corrupt system is unavoidable. Once government gets in the

business of making decisions that should be left to the marketplace, it is off to the races for the special

interests politicians love to decry but can’t live without.” (Ref. 3)

A more recent case of questionable industrial policy involves the two companies, electric

car maker Tesla and solar panel manufacturer SolarCity, which are currently seeking government approval to merge.

Both companies are “deeply unprofitable” but “benefit from a variety of federal and state policies designed to

stimulate demand among potential customers. The cost of Tesla’s cars is reduced by a $7,500 federal tax credit

and by other state incentives. . . . Similarly, SolarCity’s panels were made an attractive investment to

homeowners by the federal Solar Investment Tax Credit and by state incentives.

“It is the other benefits Tesla and SolarCity enjoy that raise eyebrows. In 2009, during

the financial crisis, Tesla was given a $465 million low-interest loan by the U.S. government, for which taxpayers

received no shares and without which the company would not have survived. The case of SolarCity is even more

striking. The innovative gigafactory in cloud-socked Buffalo is the direct result of the New York state

government’s goal of creating advanced manufacturing jobs in the city. . . . New York is spending $750

million to build and equip {the factory}. SolarCity … will lease it, essentially free, and has committed to

spending $5 billion … over the next decade. . . . {I}ndustrial policy gets into trouble when it does some of

the things federal and state governments are attempting with Tesla and SolarCity.

“First, governments are notoriously poor judges when it comes to picking individual

winners: in the absence of well-designed rules and procedures, investment in companies is often the resut of

political whims and can be hard to end. Second, the goals of a policy must be clearly defined and noncompeting:

mixing goals such as creating manufacturing jobs, encouraging solar energy and electric cars, and competing

internationally can too easily lead to an end in which none of the goals are realized.” (Ref.

2)

“The Tesla-SolarCity {merger} deal looks so bad on paper that many investors worry it’s

simply a bailout of SolarCity . . . it’s racked up more than $2 billion in losses over the past five years.

. . .

“Tesla is no exemplar of financial stability either. It’s lost $2.5 billion in the last

five years, even more than SolarCity.” (Ref. 4)

So, are Tesla and SolarCity two more examples of our government’s industrial policy gone

awry? Will they be another pair of examples of the government picking winners and losers and picking wrong? Will

the government support the merger of Tesla and SolarCity and pour in more taxpayer money in the hope of turning two

money-losing companies into one money-making mega-company? Only time will tell. Past history may not always be a

good indicator of the future, but, as anyone who bets on the horses will tell you, there is something to be said

about looking at past track records.

“Industrial policy remains controversial. Defined as the attempt by government to promote

the growth of particular industrial sectors and companies, there have been successes, but also many expensive

failures. Policy may be designed to support or restructure old, struggling sectors, such as steel or textiles, or

to try to construct new industries, such as robotics or nanotechnology. Neither tack has met with much success.

Governments rarely evaluate the costs and benefits properly.

- - -

“Clean technology has captured the imagination of several governments, which are spending

hundreds of billions in the hope of creating many jobs as well as meeting carbon-emissions targets. Many will find

they wasted money . . . Most countries are trying to do the same things and not all will succeed . . . Green

manufacturing jobs may find their home mostly in China, not America . . .

- - -

"The lessons of the past are clear. First, the more it is in step with a national or local

economy's competitive advantage, the more likely industrial policy is to succeed. Drives to spur high-tech

entrepreneurship in areas of heavy manufacturing, for instance, face a struggle . . .

“Second, policy is least prone to failure when it follows rather than tries to lead the

market . . .

“Third, industrial policy works best when a government is dealing with areas where it has

natural interest and competence, such as military technology or energy supply. The worst problems unfold when

politicians intervene in purely private domains with short-term goals, bailing out old firms to save jobs or

spending lavishly on white elephants. The present round of industrial policy will no doubt produce some modest

successes—and a crop of whopping failures.” (Ref. 5)

The government’s use of Industrial policy and coincidentally to pick winners has many

detractors. “The term, 'picking winners and losers,' gets thrown around a lot in the political world. The government

does this each and every day with tax credits for new jobs created, subsidies to boost the price of a firm's

product, or even taxpayer-funded grants to build a new company headquarters.

“The idea that the government can help stimulate economic growth and create new jobs

sounds like a productive idea on the surface. Using taxpayer funds to invest in companies that create jobs is a

good thing, right?

“Not so much, according to the data compiled by the John K. MacIver Institute for Public

Policy. Specific tax credits, subsidies, grants and other incentives only help the few. They may even harm

economic development - the exact opposite of what the incentives strive for. [Emphasis mine]

- - -

“Many studies have shown the economic value of having a lower tax burden. Businesses and

workers pay less to the government, so they have more to spend and invest in the economy. That, however, is the

argument for lower taxes in general.

“Tax credits, instead, create an unfair playing field. Only businesses that qualify for

the tax credit are rewarded, which may give them an advantage over other firms in the market.

- - -

" 'Even though credits lower the tax burden of a particular tax filer, in most cases we see

them as poor tax policy,' . . . 'Some businesses might get the benefit of a preference, but other businesses that

aren't engaging in whatever activity is deemed ‘favorable’ are stuck paying the full sticker rate of the tax.'

“Typically these credits favor large firms with political connections.

“Bigger firms can use their vast resources to ensure they qualify for different tax

credits. These firms normally have a government relations department that dedicates its time to finding and

receiving government incentives. Smaller firms may not be able to compete, leaving them at a disadvantage.

- - -

“Subsidies are another form of government incentives that can actually hurt economic

growth. They artificially inflate the price of many items, but typically spread it over the entire country.

“For example, taxpayers pay an extra $3.7 billion every year in sugar price supports.

That is lot of money, but it only costs each man, woman, and child in America an extra $12 a year. It is very

unlikely that anyone will write their congressman or fight against that small of a personal cost. But, the sugar

farmers will lobby for it continuously because they each get a major chunk of that subsidy.

“Even though this provides a nice incentive for the sugar industry, the sugar-using food

and beverage industry has lost 127,000 jobs since 1997. At the same time, US and Mexican sugar production has

increased up to 25 percent because of the artificial price supports leading to massive surpluses.

“This is a real world example of firms producing a product based on the incentive {aka

Industrial Policy or choosing winners and losers}, and not what the market demands.” (Ref.

6)

Another example of the government’s failed attempt to institute a beneficial industrial

policy is that of the ethanol subsidy to America’s farmers. It was supposedly conceived with the best of intentions

– to aid the environment - but now turned into a political issue – that of subsidizing U.S. famers. It is

becoming increasingly clear that the government’s rush to replace gasoline with ethanol was probably a

bad move.

Ethanol is stupid, wasteful and bad for cars (because its corrosive and

inefficient).

Biofuels were supposed to be better for the environment, particularly global warming,

and lessen our dependence on foreign oil. The assumption was that converting plants into fuel was “carbon neutral”

and that every gallon of oil we replaced with corn was one less we hade to buy from overseas. The fact that

it also lined the pockets of agribusinesses and the politicians who love them was supposed to be a total coincidence

and irrelevant to this good and noble policy.

However, A new study from the University of Michigan confirms what pretty much

everyone knew all along. Researchers found that biofuels actually create more greenhouse gasses than simply using

petroleum. The study showed that When it comes to the emissions that cause global warming, it

turns out that biofuels are worse than gasoline.

“Another study by the University of Tennessee found that “in the decade since

the U.S. imposed the Renewable Fuel Standard – and after $50 billion in subsidies – corn-based ethanol ‘created

more problems than solutions’ and hampered research on other kinds of biofuels.” [Emphasis mine]

(Ref. 7))

Additionally, growing corn for inefficient fuel removes farmland from food production,

resulting in increased food prices.[7])

“Thanks to the ongoing shale oil revolution, America now has greater oil reserves than

Saudi Arabia and Russia. Domestic oil production produces far more – and far better paying – jobs than ethanol

production.” (Ref. 7) But, the ethanol subsidies continue, demonstrating once

again that bad industrial policy decisions are extremely difficult to reverse, especially when politics and voter

support of politicians are involved. Good industrial policy and wise politicians seem to be somewhat mutually

exclusive. Instead, industrial policy - good or bad - and politics/politicians – wise or unwise - are heavily

intertwined.

The establishment and implementation of effective government industrial policies requires

wise politicians. Picking and choosing winners and losers probably should not be part of this process – that should

normally be left to the competitive and capitalistic marketplace. The corollary question remains, however – do we

have any wise politicians, or just politicians?

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References:

- Capitalism Behaving Badly, David Rotman, MIT Technology Review, Pages 96-100,

Vol. 119/No. 6,

October 2016.

- From the Editor, Jason Pontin, MIT Technology Review, Page 2, Vol. 119/No. 6,

October 2016.

- Government Picking Winners and Losers = Corruption, Gary Johnson, The Huffington

Post,

20 December 2011.

- Elon Musk’s House of Gigacards, Peter Burrows, MIT Technology Review, Pages 58-63,

Vol. 119/No. 6,

October 2016.

- Picking winners, saving losers, Gary Johnson, The Economist,

5 August 2010.

- Winners and Losers: The Impact of Government Incentives, Nick Novak, MacIver

Institute, 16 January 2014.

- Research proves ethanol’s only useful to pols, Jonah Goldberg, Boston Herald,

Page 17, 5 September 2016.

|

|