|

Most of what we see and hear about Israel has to do with tourism,

the on-going hostility of Israel’s Arab/Muslim neighbors, the ongoing war with Gaza and its

Hamas rulers, the fruitless “2-state peace negotiations” with the Fatah rulers of the West

Bank, Israel’s vibrant technology and economy, the continuing threat of annihilation by

Iran’s theocratic government, and the call to Boycott, Divest, and Sanction (BDS) Israel

by anti-Semites around the globe. But perhaps the most important feature of Israel is the

historical and religious significance it holds for three of the world’s major religions.

Yet, there is another side to Israel that is perhaps of equal or

greater importance than those features listed above. This other side of Israel is the diverse,

often contentious, yet mostly united people of this very unique Mid-East nation. Summarized

in what follows is my attempt to outline some of the characteristics of this other side of

Israel. Much of what follows is derived from the references listed, while some comes from

personal observations obtained over some ½-dozen annual trips to the country as a tourist/volunteer.

To some, Israel appears to be one more-or-less semi-homogeneous Jewish

nation. In actuality, this is a gross misconception. Israel is composed of a number of disparate

elements that sometimes work together and sometimes are in violent conflict with each other.

Other countries in the Middle-East with similar internal divisions either suffer from constant

brutal conflict that claims tens of thousands of lives, or else give the false appearance of unity

only when under the thumb of ruthless, intolerant and despotic regimes. In the case of Israel,

the nation functions as the only open democracy in the region – and, despite the occasional

appearances of complete chaos, it functions extremely well.

Background

Israel is home to a widely diverse population from many ethnic, religious,

cultural and social backgrounds. Also, relative to its population, Israel is the largest

immigrant-absorbing nation on earth. Immigrants come in search of democracy, religious freedom,

and economic opportunity.[1] Around 7

million people live there today, including approximately 5-1/2 million Jews and 1-1/4

million Arabs.

Israeli society encompasses a wide spectrum of lifestyles, ranging

from religious to secular, from modern to traditional, from urban to rural, and from communal

to individual.

Jews have lived in the land of Israel for nearly 4,000 years, going back

to the period of the Biblical patriarchs (c.1900 B.C.). Over that span of time, there has

been a continuous Jewish presence

in the land of Israel. It has always been the aspiration of the Jewish people to live there

and to practice the world's first monotheistic religion in peace.

The concluding words of Israel's national anthem, Ha Tikvah

(“The Hope”) summarize that aim: “The hope of 2000 years:/ To live as a free people/ In our own

land/ The land of Zion and Jerusalem.”

Following the expulsion of most of the Hebrew people from Israel by

Rome some 2,000 years ago, Jews were dispersed to other countries throughout the world,

where they established many large Jewish communities – “the Jewish Diaspora”. In

this Diaspora, these refugees from the land of Israel attempted - unfortunately too often

without success - to live in peace with the peoples of their host countries and to continue to

practice their religion.

The biblical concept of the “ingathering of the exiles” always persisted.

At the end of the 19th century, this concept was given a modern political manifestation in the

form of Zionism. In 1948, the United Nations approved statehood once again for the Jewish people.

In 1950 the State of Israel enacted the “Law of Return”,

which allows every Jew the right to return to Israel and, upon entry, to automatically become

an Israeli citizen. Members of other faith communities may apply for Israeli citizenship as they

would in any other country. By law and biblical injunction, all Israeli citizens

enjoy the same rights.

During the first 4 years of statehood, mass immigration doubled Israel’s

Jewish population from 650,000 to about 1.3 million. A majority at that time was comprised of the

established Sephardic community, veteran Ashkenazi settlers, and newer Holocaust survivors.

A large number of recent Oriental Jewish immigrants from the Islamic countries of North Africa

and the Middle East formed the minority. Jews from Europe constituted the Ashkenazi

community while Jews from North Africa and the Middle-East comprised the Sephardic

community.

The Ashkenazi Jews from Europe assumed political control of the new nation

while the Sepharidic Jews were placed in a lower social strata. In the 1950s, the 2 groups

coexisted virtually without social or cultural interaction. The Jews of North African and Middle

Eastern backgrounds finally expressed their frustration and alienation in anti-government protests

which in the 60s and 70s became demands for greater political participation, compensatory

allocations of resources and affirmative action to help close the gap between them and the

dominant mainstream Ashkenazis.

In 1984 a Sephardi-Orthodox religious political party, Shas

was founded. Its influence grew rapidly and it soon became Israel’s third-largest political

party, holding the balance of power in a country where no political party has ever achieved

an outright majority. By the end of the 1980s, the protest movements had become marginal,

marriages between people of Sephardi and Ashkenazi origin became more common, and the

inter-ethnic social gap had narrowed.

During the 1980s and 1990s Israel continued to receive new immigrants.

The largest wave was comprised of Jews from the various communities of the former Soviet Union.

Since 1989, over one million Russians have settled in the country, among them many highly-educated

professionals, well-known scientists and acclaimed artists and musicians.

The 1980s and 90s also witnessed the arrival of some 50,000 Ethiopian

Jewish immigrants in two massive airlifts. They are believed to have been living in Ethiopia

since the time of King Solomon. These Ethiopian Jews are readily distinguished from

their Ashkenazi and Sephardic brethren by the color of their skin – These Ethopian Jews are

black-skinned pople.

Approximately 23% of Israel's population is non-Jewish. Although often

defined collectively as Arab citizens of Israel because of the linguistic commonality of many of these people,

this group includes a number of different communities, each with distinct characteristics.

Some are not even of Arab background.

Almost one million mainly Sunni Muslims reside in small towns and

villages in Israel, over half in the north of the country. An estimated 170,000 Muslims,

belonging to some 30 tribes, live scattered over a wide area in the south. Formerly nomadic

shepherds, Bedouin Arabs are currently in transition from a tribal social framework

to a permanently settled society and are gradually entering Israel's labor force. Many

voluntarily serve in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).

About 113,000 Christian Arabs live in urban areas of Israel including

Nazareth, Shfar'am and Haifa. The majority are affiliated with the Greek Catholic, Greek

Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches.

Some 106,000 Arabic-speakers living in 22 villages in northern Israel

constitute a separate cultural, social and religious community called the Druze. The

Druze religion calls for complete loyalty to the government of the country in which they reside.

Many Druze therefore serve in the IDF.

Concentrated in two villages in northern Israel are about 4,000

Circassians who are Sunni Muslims. They share neither the Arab origin nor the

cultural background of the larger Muslim community of Israel. While the Circassians maintain

a distinct ethnic identity, they still participate in Israel's economic and national affairs

without assimilating either into Jewish society or into the Muslim

community.[2]

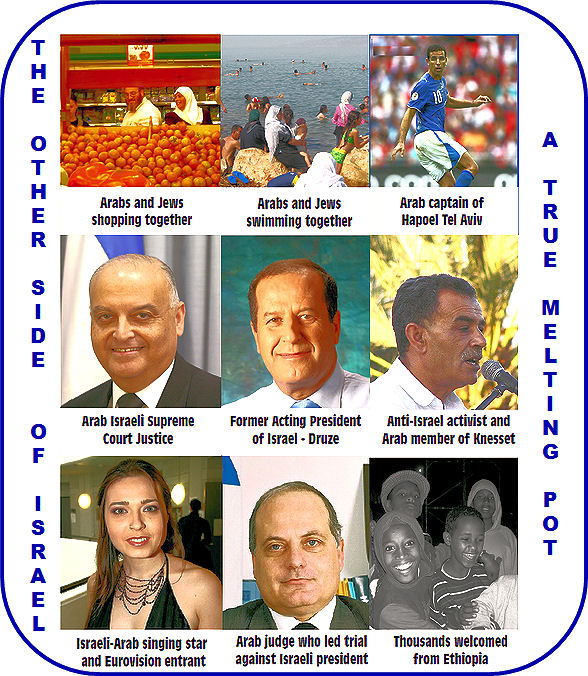

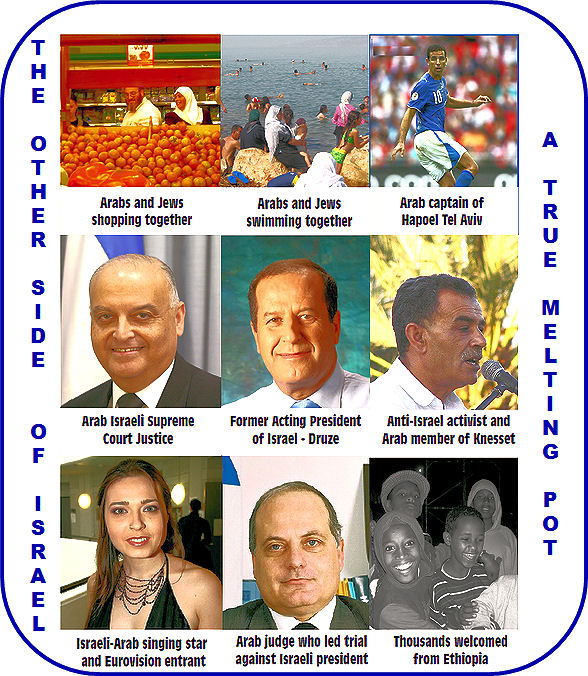

Israel-haters have accused the nation of being racist and of

practicing Apartheid. Yes, Israel has ethnic and racial tensions. But,

these are minor and truly irrelevant in comparison to the freedoms, rights and opportunities

afforded to all of Israel’s citizens and residents. Compared to other countries in the region,

and, in fact, to most other nations throughout the world, Israel is an ethnic, religious and

racial utopian melting pot. One illustration of this fact is that “one of Israel’s top

football (soccer) clubs, Bnei Sachnin, – a small Arab village in the Galilee - won the Israel Cup in

2004 and participated in the UEFA (Union of European Football Associations) Tournament.

The team is made up mostly of Israeli Arabs but also includes a number of Africans

‘on loan’ and a manager, as well as several key players, who are Jewish. No other

country in the world has a national team in which Whites, Blacks, Arabs, Jews, Christians,

Muslims are all represented. If any other country had such a team, it would undoubtedly be

the subject of abundant praise by the international media. [Emphasis mine]

(Ref. 3)

Non-Jewish Israelis

Israeli-Arabs

In what follows, I have chosen to use “Druze” and “Bedouin” spellings

for these communities. The spellings “Druse” and “Beduin” are often used as well.

“The topic of the Arab sector in Israel is politically charged and

represents contradicting narratives – one Jewish, the other Arab. Just as there are differences

of opinion within the Jewish sector, there are variances in the Arab sector, and attitudes toward

the Jewish sector, the state and its institutions can often even represent polar opposites.

“To start with, there is no such thing in Israel as one ‘Arab sector’;

rather, there are several Middle Eastern populations, some of which are not Arab, and they differ

from one another in religion, culture, ethnic origin and historical background. Parenthetically,

it is debatable whether there is one cohesive Jewish sector in Israel. Therefore, when we use the

terms ‘the Arab sector’ and ‘the Jewish sector,’ it will be only for the sake of simplicity.

“Within the Arab sector {in Israel}, there are a number of ethnic groups

that differ from each other in language, history and culture: Arabs, Africans, Armenians,

Circassians and Bosnians. These groups usually do not mingle, and live in separate villages or

in separate neighborhoods where a particular family predominates. For example, the Circassians

in Israel are the descendants of people who came from the Caucasus to serve as officers in the

Ottoman army. They live in two villages in the Galilee – Kafr Kama and Rehaniya – and despite

their being Muslim, the young people do not usually marry Arabs.

“The Africans are mainly from Sudan. Some of them live as a

large group in Jisr e-Zarka and some live in family groups within Bedouin settlements in the South.

They are called ‘Abid,’ from the Arabic word for ‘slaves.’ The Bosnians live in family

groups in Arab villages.

“The Armenians came mainly to escape the persecution that they

suffered in Turkey in the days of World War I, which culminated in the Armenian genocide of 1915.

“In general, it can be said that the Arab sector is divided culturally

into three main groups: urban, rural and Bedouin. Each group has its own cultural characteristics:

lifestyle, status of a given clan, education, occupation, level of income, number of children,

and matters connected to women – for example, polygamy, age of marriage, matchmaking or dating

customs, and dress.

“The residents of cities – and to a great extent also the villagers – see

the Bedouin as primitive, while the Bedouin see themselves as the only genuine Arabs; in their

opinion, the villagers and city folk have lost their Arab character. The Arabic language expresses

this matter well: The meaning of the word ‘Arabi’ is ‘Bedouin,’ and some of the Bedouin tribes are

called ‘Arab’ – for example, Arab al-Heib and Arab al-Shibli in the North.

“The Bedouin of the Negev classify themselves according to the color of

their skin, into hamar (red) and sud (black).

“Bedouin would never marry their daughters to a man darker than she is,

because they do not want their grandchildren to be dark-skinned. Racist? Perhaps.

“Another division that exists in the Negev is between tribes that have a

Bedouin origin, and tribes whose livelihood is agriculture (fellahin), who have low status. A

large tribe has a higher standing than a small tribe.

“The Arab sector in Israel is divided into Muslims, Christians, Druze

and Alawites. The Christians are subdivided into several sects – Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant

– and among the Muslims, there is a distinct sect of Sufis, who have a significant

presence in Baka al-Gharbiya. There is also a Salafi movement in the country.

The Islamist movement is organized along the lines of the Muslim Brotherhood.

“The religion of the Druze is different from Islam, and Muslims

consider the Druze heretics. Because of this, the Druze are supposed to keep their religion

secret, even from each other, and therefore most are juhal (ignorant, of religious matters).

Only a small number of the elder men are aukal (knowledgeable in matters of religion). In the

modern age, there have been a number of books published about the Druze religion.

“The Alawites in Israel live in the village of Ghajar, in

the foothills of Mount Hermon, and some live over the border in Lebanon. They are also considered

heretics in Islam, and their religion is a blend (syncretism) of Shi’ite Islam, Eastern

Christianity and ancient religions that existed in the Middle East thousands of years ago.

Their principal concentration is in the mountains of al-Ansariya in northwest Syria, although

some are in Lebanon and some migrated southward and settled in Ghajar.

“The meaning of the word “Ghajar” in Arabic is “Gypsy,” meaning foreign

nomads with a different religion. In Syria, the Alawites have ruled since 1966. The Assad family

is part of this heretical Islamic sect, and this is the reason for the Muslim objection to their

rule. According to Islam, not only do they not have the right to rule, being a minority, but

there is significant doubt as to whether they even have the right to live, being idol worshipers.

{Theologically, Alawites claim to be Twelver Shiites, but traditionally they have been

designated as “extremists – ghulat” and outside the bounds of Islam by the Muslim mainstream for

their deification of Ali ibn Abi Talib or Ali, who was the cousin and son-in-law of the Islamic

prophet Muhammad.}

“Some parts of the Arab sector are communities that have lived in the

land now called the State of Israel for hundreds of years, but a significant part is the offspring

of immigrants who migrated here mainly in the first half of the 20th century – especially after

1882, when Petah Tikva was established. {The reason for this influx was the economic opportunities

afforded by the arrival of the Jews escaping from the pogroms of Russia and Eastern Europe and the

beginning of the Zionist development of Palestine from a land of desolation to one promising to

once more be the land of milk and honey.}

“Many people from neighboring lands migrated here at that time to work

in the Jewish farming communities.

“Many migrated from Egypt even earlier, to escape being impressed into

forced labor as the Suez Canal was being dug. This is how the al-Masri, Masarwa and Fiumi families,

as well as many others, came {to Israel}, with names testifying to their Egyptian source. Other

families have Jordanian names (Zarkawi and Karaki, for example), Syrian ones (al-Hourani, Halabi),

Lebanese (Surani, Sidawi, Trabulsi) and Iraqi (al-Iraqi).

“The Arabic dialect that most of the Bedouin in the Negev speak is a

Saudi-Jordanian dialect, and because of their familial ties to tribes living in Jordan, when

the Bedouin become involved in matters of blood-vengeance, they escape to family members in Jordan.

“The connection between Arab families in Israel and groups in neighboring

countries should not be surprising, because until 1948 the borders of Israel were not hermetically

sealed, and many Arabs of “Sham” (Greater Syria) wandered almost totally unimpeded, following their

flocks and the expanding employment opportunities.

“The division between traditional and modern outlooks exists in each group,

meaning that in each group there is a subdivision: those who are more connected to the tradition of

the group and those who are less connected. Among the young, one sees more openness and less adherence

to group tradition, and it can be assumed that the youth of the next generation will generally

adhere even less to the group’s traditions. This is obvious among the Bedouin groups, because

among the young there are more than a few who challenge the Bedouin’s socially accepted ways.

Education also plays an important role in the changing attitude toward

tradition, because Arab academics are usually less linked to social tradition and the framework

of the clan, and live more within the framework of nuclear families (father, mother and children).

They also tend to move to more open areas, such as mixed cities like Acre, Ramle and Lod, and even

to Jewish cities such as Beersheba, Karmiel and Upper Nazareth, where they adopt a modern lifestyle.

“The shift to the city is also connected to a change in the source of

livelihood. There are more {opportunities} in the independent professions and fewer in agriculture –

a change due partly to the confiscation of the lands of absentees after the War of Independence.

“Beyond the religious dividing line that differentiates Jews and non-Jews,

another basic division exists between the country’s Jewish and Arab sectors in their general approach

to the state.

“For most of the groups within the Jewish sector, the State of Israel

fulfills two roles. One is the political and governmental embodiment of the Jews’ aspirations to

return to themselves and to regain the independence and sovereignty over the land of their fathers

that was stolen from them after the Second Temple’s destruction.

“The symbols of the state are Jewish: the national anthem, which includes

the words “the Jewish soul yearns”; the flag, which represents the prayer shawl; the Star of David;

and the seven-branched menorah. Hebrew is the official language of the state, and on Jewish holidays,

the governmental institutions are closed.

“The second role of the state in the eyes of most Jews is functional:

to provide its citizens with security, employment, livelihood, health, education, roads, bridges

and social services.

“For the Arab sector, the first role does not exist. The State of Israel

is not the embodiment of their diplomatic and political dreams. The national anthem is not their hymn,

the symbols of the state are not their symbols, and {Israel’s} Independence Day is their

Nakba (disaster). The second role as well, the functional, is only partly fulfilled in

matters of education, planning, roads and infrastructure. One may argue about the causes and reasons,

but the facts are clear: How many Arab members are there on government companies’ boards of directors?

How many Arab judges are there in the High Court? What is the proportion of Arabs in the academic staff

of universities? That said, one cannot ignore the phenomenon of reverse discrimination, either. Laws

of planning and building that are observed almost fully within the Jewish sector are very loosely

observed within the Arab sector, especially in the Bedouin sector in the Negev. How many thousands

of buildings have gone up in the Negev without building permits, on land that does not belong to

Bedouin? How is it that there are no sidewalks in Umm el-Fahm, and the distance between the buildings

is about the width of the cars? Another example of reverse discrimination exists in the area of

marriage. If a Jew dares to marry a woman before he has completed the process of divorce from his

present wife, he will find himself behind bars. But if an Arab marries a second, third or fourth

wife, the state pays a monthly children’s allowance for each wife separately and without asking

too many questions.

{During my annual visit to Israel this past winter,I passed a number of

Arab villages in which there were piles of construction rubble, abandoned buildings, trash and

uncompleted new buildings. The shabbiness of these Arab villages contrasted sharply with the

various Jewish communities in Israel, where no such dilapidation and shabbiness could be seen.

I asked our guide what was the cause of the poor condition of these Arab villages. His

explanation was that in Arab villages there was a reluctance on the part of the Arab-run municipal

governments to collect taxes – it is viewed as improper for one Arab to collect taxes from another

Arab. As a result these Arab municipalities don’t have the financial resources to clean up their

environment. Only a small percentage of Arab residents of these Arab villages pay their municipal

taxes. This contrasts sharply with the Jewish communities where nearly all residents pay their

full share of municipal taxes.}

“Another case of discrimination in favor of Arabs exists in the area of

housing. About 90 percent of the Jewish sector lives in apartments, and about 10% in private houses.

In the Arab sector the picture is the reverse.

“But the characteristic that most unites the country’s Arab sector is the

environment in which they live. All the Arabs {outside of Israel} live in one of two situations: in

dictatorships in their homeland, or in dictatorships in their diaspora. There is almost no

Arab community that has lived in its homeland for dozens of years in a truly democratic state.

{In marked contrast,}The Arab citizens of Israel are the only Arab group that lives on its land

(especially if you ignore the lands from which they originated) {under} a democratic regime that

honors human rights {along with religious and} political freedoms. This is the reason Arabs outside

Israel envy Israel’s Arab citizens and call them ‘Arab al-Zibda’ – ‘butter Arabs.’”

[Emphasis mine] (Ref. 4)

Changes are occurring in some sectors of the Israeli-Arab community, where

recognition of the right of Israel to exist is being accepted, as is the obligation to serve in the

armed forces of the country in which you are a citizen.

”The Arab parties in the Knesset {Israeli parliament} oppose Arabs serving

in the Israeli Defense Forces or in civilian service, and some of their members do not want Israel

to remain a Jewish state. {A} new party, though, advocates allegiance to Israel as a Jewish state

and participation in military or national service alongside most Jewish Israelis.”

(Ref. 5)

An Arab-Israeli recently announced that he is founding a Christian-Arab

political party that will recognize Israel as a Jewish state. The party name,

Brit Hachadasha,

in Hebrew means both ‘new allies’ and ‘children of the New Testament.’ The party will urge

Christian-Arab Israelis to serve in the army or perform civilian national service. Today,

approximately 10% of Israeli’s Arab citizens are

Christians.[5]

According to the party’s founder, “At least in Israel, those who stayed here

have been given the right to be a citizen and to integrate. But Israel’s first demand, which I

support – and which needs to be understood – is that Israel is the home of the Jewish

people.” (Ref. 5)

In still one more instance of support for the Jewish state, a young

Israeli-Arab Christian woman created a stir recently when she posted a strong statement in

support of Israel on Facebook. She stated: “I am an Arabic-speaking Christian, but I am not

an Arab. I ask, with all due respect, that you not say in the name of Christians that ‘we

are Palestinians.’ Hear me, we are not Palestinians and we don’t care about them. We are

Israeli Christians, covered in blue and white in our hearts and souls. … We simply love

blue and white. And we as Christians will enlist in the IDF and will serve the

state…‘” (Ref. 5)

Ahmadiyyat Muslims

“Haifa is Israel's third largest city, the capital of northern Israel and

gateway to the Galilee, and home to over a quarter of a million residents. Its outstanding record of

coexistence among its diverse population of Jews, Christians, Muslims, Bahá'is, Druze and Ahmadis is

a model of cultural and religious pluralism and harmony.”

(Ref. 6)

The Ahmadiyyat Muslims arrived in the British Mandate of Palestine

in 1927 and found a home in the suburb, then a village, of Kababir in Haifa in 1928. Rather than following

the clerical literature of Islam, they adhere only to the text of the Quran and to the traditions of the

Prophet Muhammad. They encourage self-learning and the idea of personal experience with God. The Ahmadis

are a minority in Israel and in the world and have been persecuted in many countries, mainly Islamic

countries that have deemed the Ahmadis as heretic. Israel, however, is perhaps the only nation in the

Middle East that guarantees their safety to practice their religion and, therefore, the community has

been able to expand. They have built the Mahmood Mosque and an adjoining community center in the

Kababir section of Haifa. The relations between the Ahmadiyyat Muslims and the Jews has been excellent,

which cannot be said of their relations with the rest of the Muslim

world.[7]

I have personally visited the Kababir neighborhood in Haifa, visited the

Mahmood Mosque and its adjoining Muslim community center, and talked with one of the Ahmadi religious

leaders. I can attest to the fact that Haifa Ahmadis are fully integrated into Israeli society, as

are nearly all the Arabs and Muslims in Haifa.

Israeli-Druze

The members of the Druze community in Israel are staunch supporters of the

Jewish state. In Israel’s several wars with its Arab neighbors, a disproportionate number of Druze have

fallen in defense of Israel. The bond between Jewish and Druze soldiers is commonly known by the term

"a covenant of blood".

The Druze are of Arab descent, but they do not practice the Islamic religion.

The Druze religion was established at the beginning of the 11th century but only in the 19th century were

they recognized as an independent congregation by the Ottoman regime. Their culture is Arab and their

language Arabic, but they opted against mainstream Arab nationalism in 1948 and have since served

(first as volunteers, later within the draft system) in the Israel Defense Forces and the Border

Police.[8]

The Druze are a religious minority in Israel. In 2010, there were 125,300 Druze

living in the country,[9] – many in and around the Druze

towns of Isfiya and Daliyat al-Karmel near Haifa. In 1957, the Israeli government

designated the Druze as a distinct ethnic community at the request of its communal leaders. The Druze

are Arabic-speaking Citizens of Israel and they serve in the IDF. Members of the community have

attained top positions in Israeli politics and public service. Many Druze of college age attend the

nearby Haifa University and Technion, and there are members of the faculties at these universities

that are Druze.

The Druze are very communal or clannish. Intermarriage outsize the Druze

religion is forbidden. The Druze are, however, very hospitable to outsiders. I spent several very

pleasant hours in Isfiya, learning about the Druze people and their religion and enjoying a delectable

strictly kosher meal in the home of a Druze family.

The Druze community reveres Jethro, the non-Jewish father-in-law of Moses.

It has been claimed that the Druze are actually descendants of Jethro. According to the biblical

narrative, Jethro joined and assisted the Israelites in the desert during the Exodus from Egypt,

accepted monotheism, but ultimately rejoined his own people. In fact, the tomb of Jethro near

Tiberias in Israel is the most important religious site for the Druze community.

The relationship between Israeli Jews and Druze since Israel's independence

in 1948 is both emotional and practical, partly because of the considerable number of Israeli Druze

soldiers that have fallen in defense of Israel during the country’s many wars with its Arab neighbors.

Many Druze-Israelis have achieved prominent status in Israel. A Druze

politician, Majalli Wahabi, served as the acting President of Israel in February

2007.[10] Five Druze lawmakers

were elected to serve in the 18th Knesset, a disproportionately large number considering their

population.[9] Reda Mansour a Druze poet, historian

and diplomat, explained: "We are the only non-Jewish minority that is drafted into the military,

and we have an even higher percentage in the combat units and as officers than the Jewish members

themselves. So we are considered a very nationalistic, patriotic

community."[10]

In 1973, the Zionist Druze Circle, a group whose aim was to encourage the

Druze to support the state of Israel fully and unreservedly was

founded.[10]

In 2007, the group’s founder stated that “‘The state of Israel is a Jewish

state as well as a democratic state that espouses equality and elections. . ., the fate of Druze and

Circassians in Israel is intertwined with that of the state. This is a blood pact, and a pact of the

living. We are unwilling to support a substantial alteration to the nature of this state, to which

we tied our destinies prior to its establishment’ he said. As of 2005 there were 7,000 registered

members in the Druze Zionist movement. In 2009, the movement held a Druze Zionist youth conference

with 1,700 participants.

“In a survey conducted in 2008, {a report from} the Tel Aviv University

found that more than 94% of Druze youth classified themselves as ‘Druze-Israelis’ in the

religious and national context.

“On 30 June 2011, {The Israeli newspaper} Haaretz reported that a growing

number of Israeli Druze were joining elite units of the military, leaving the official Druze battalion,

Herev, understaffed.” (Ref. 10) In other words, the

Druze youth were opting to be integrated into elite IDF units, rather than serving in an all-Druze

IDF battalion.

The IDF Sword Battalion (Hebrew: Gdud Herev), formerly known

as Unit 300 and as the IDF Minorities Unit, is an Arabic-speaking unit of the

IDF. Non-Jewish minorities also serve in the Druze Reconnaissance Unit and the Bedouin

Trackers Unit. In 1987, “Unit 300" was officially renamed the ‘Sword

Battalion.”[11]

The Minorities Unit was formed in the early summer of 1948 by incorporating a

unit of Druze defectors from the Arab Liberation Army and small numbers of Bedouins and Circassians.

It has fought in every war since. Today, most members of the unit are Druze, but there are also

Bedouins, Circassians and Christian and Muslim Arabs. The unit has produced several generals. The

Minorities Unit has a small elite Sayeret special forces

branch.[11]

Today, Druze and Circassian men are subject to mandatory conscription

into the IDF. In the mid-1950s, the Druze leadership appealed to David Ben-Gurion, then Minister

of Defense, to draft Druze men on the same basis as Jews. The State Defense Act of 1949, which

called for drafting all individuals in the country, allowed the minister to issue exemptions

for certain groups. The Druze asked that their exemption be canceled. Originally, they served

in the framework of a special unit. Since the 1980s, Druze soldiers have joined regular combat

units, attaining high ranks and commendations for distinguished service. 83% of Druze boys serve

in the IDF and 369 Druze soldiers have been killed in combat operations since

1948.[11]

There are four Druze villages on the Golan Heights, which Israel captured

from Syria and later formally incorporated into the State of Israel. In the late 1970s, the Israeli

government offered citizenship to all non-Israelis living in the Golan, which would entitle them

to an Israeli driver's license and enable them to travel freely in Israel. Most Druze in the region,

however, continue to regard themselves as Syrian citizens, with less than 10% having accepted Israeli

citizenship. As Israel does not recognize the Syrian citizenship of the Golan Heights Druze,

they are defined in Israeli records as "residents of the Golan Heights." Golan Heights Druze are not

drafted by the IDF. In 2012, young Druze applied for Israeli citizenship in much larger numbers than

in previous years because of the ongoing Syrian civil war. Also, because of bloodshed in Syria, many

Golan Heights Druze who were attending schools in Damascus have now switched to schools in Israel.

Public support for the Syrian government of Bashar al-Assad has historically been high among Golan

Druze and Assad's government had secured agreements with the Israeli government to permit Golan Druze

to conduct trade across the border with Syria.[10]

Israeli-Bedouins

Israeli Bedouins have a schizophrenic relationship with Israel.

These Bedouin Arabs are divided in their views of Israel, with some acting as loyal citizens of the

state, while others side with Israel’s enemies in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“Bedouin citizens of the State of Israel hold divergent views about the

Israeli state. Some Bedouin Israelis are very loyal to the Jewish state. These Bedouin proudly serve

in the IDF as Israeli Arab soldiers, viewing it to be a family tradition, and some of them even

work for the Israeli government in senior level positions. They love the vibrant Israeli democracy

and view Israel to be a country that respects their rights. However, other Israeli Bedouins,

especially the ones living in unrecognized villages in Southern Israel, support the Palestinians

and engage in anti-Israel activism.” (Ref. 12)

"We're not big Zionists, but we are proud Israelis." This is how a

Bedouin, who has a master's degree in Political Science from Tel Aviv University and serves in

Israel’s Foreign Service, describes his own people, the Bedouin. "The Bedouin are more tribal

than nationalistic," he said. It’s that deeply ingrained tribal culture that has allowed the

Bedouin to survive centuries of nomadic existence, but it’s also the trait that presents barriers

to their continued wellbeing in modern Israel.[13]

With a birth rate amongst the highest in the world, the Israeli Bedouin

population has grown tenfold since the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. Today Bedouins

comprise almost 3% of the population of Israel, but in the Negev desert region, Bedouins make up

25% of the residents.[13]

Most of the Bedouin in the Negev hail from a region in the north of the

Arabian peninsula from where they migrated between the 14th and 18th centuries, making them

relatively recent arrivals in Israel. Historically, the Bedouin have been nomadic or semi-nomadic

tribes, traveling from one grazing pasture to another. The Bedouin organize themselves around

clans of extended family members and it’s not unusual for a Bedouin man to father several dozen

children with different wives.[13]

“In 1948, when Egyptian and Saudi Arabian forces invaded Israel, the Negev

was turned into a battleground. Some 90,000 Bedouin fled to Egypt or Jordan, and by the end of 1948,

only 11,000 remained in the deserts of southern Israel. The newly independent Jewish state saw the

Negev as a potential area for growth and development, and gave little thought to the Bedouin living

there. Since the Negev constitutes 60% of Israel’s total land mass, every Israeli government since

1948 has tried to preserve Negev land for future development, and ignored Bedouin claims to the area.

Despite this core land conflict, Israel was the first body to take any interest at all in the

Bedouin people, granting them citizenship, and providing them education, medical care, and access

to the social benefits enjoyed by every Israeli citizen since the implementation of the National

Insurance Law of 1953. Nevertheless, Israel’s government policy has “never been geared to Bedouin

needs or desires”. (Ref. 13)

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Israeli government began to push the

Bedouin to settle in seven towns in the northern Negev. Israel’s goal was to make it easier to

provide basic services and modernize the population, as well as to try to prevent the Bedouin from

spreading out over the Negev, and blocking development of new Jewish communities. Today, around

half the Bedouin people of the Negev live in these towns, which were built without careful

planning or input from Bedouin leaders. The remaining 50 percent prefer to continue to live

a traditional nomadic lifestyle in 45 unrecognized villages, which are not hooked up to the

national electric, sewage, or water systems. Today, many Israeli politicians and intelligence

officials regard the Bedouin with alarm, as their towns have become breeding grounds for crime

as well as rising Islamic fundamentalism. [13]

Traditionally Islam was never a prevalent factor in Bedouin life

since Islam stresses that one’s number one allegiance should be to Allah, whereas Bedouin primary

allegiance has always been to the tribe. It’s only in recent years that this has begun to

change, as radical Islamists have seen in the rapidly growing Bedouin population an opportunity to

expand their reach within Israel’s borders.

Many Israeli demographers warn that the "Bedouin problem" in the Negev

threatens the stability of Israel's southern region. One expert predicts that, "Within five years,

the next intifada will break out in the Negev." He lays out a dire scenario, pointing to security

problems, crime, drug dealing, and extortion of Negev business owners and farmers by Bedouin

gangs.[13]

Bedouin ties with their brethren in Jordan, Syria, and Egypt raise other

security concerns for Israel, as Bedouin identity takes on a new and more radical twist. “There is

no difference between the Bedouin and the Palestinians,” declared a Bedouin leader in the Negev in

2007, expressing sentiments not necessarily shared by Bedouin from the

Galilee.[13]

As noted, one segment of the Bedouin population looks unfavorably upon the

State of Israel. “Not too long ago, thousands of Israeli Bedouins marched through the city of

Be’ersheva, waving PLO flags and banners of the Israeli Islamic Movement, while chanting, ‘With

our blood and our spirit we will redeem the Negev.’ These Israeli Bedouin were protesting a

decision by the Israeli government to settle them in permanent homes as part of a compromise

agreement that recognizes Bedouin legal rights in over 60 percent of the land in the Negev that

they have squatted on illegally {for decades, if not centuries}.

“For these Bedouin, this compromise deal was not good enough because

they believe the Negev which makes up 66% of the State of Israel, belongs to the Palestinians

and not the Jewish people, despite the ancient Jewish connection and presence in the Negev.

These Southern Israeli Bedouin are cooperating with anti-Israel forces who seek to have the

Negev become Palestinian, thus connecting Gaza to Judea and Samaria, as well as Egypt.”

(Ref. 12)

One of the most sensitive issues for the Bedouin minority is army

service. Israeli Arabs are exempt from the mandatory army service, but since the

beginning of the state, a significant number of Bedouin have volunteered to serve in

Israel’s defense forces. In 1946, a Bedouin tribal leader sent some of his men

to fight alongside the Jewish people in their struggle for independence. Ever since that

date, there has been a Bedouin presence in the Israeli Army, which continues to grow by

the year. Bedouins mainly do tracking or scouting activities in the IDF, with the Israeli

Army’s Desert Reconnaissance Unit consisting entirely of Bedouin soldiers, although Bedouins

can be found serving Israel in other capacities. There is even a memorial for Bedouins who

have died fighting for the State of Israel in the

Galilee.[12]

An IDF Bedouin Major on the Golan Heights explained his family

tradition of serving the State of Israel: “It’s a legacy – it’s something that has been

passed on from generation to generation in my family. My father and his father served in the

army too.” He claimed, “I will do whatever is required from me to do the job with the full

faith in the service of the Israeli state. Yes, I have fought against Muslims in Gaza. And I

would fight again if I had to. Israeli Muslims who don’t serve in the IDF should be ashamed

for not serving their country.” [12]

One IDF medic whose father is Bedouin, stated, “I think we can call

ourselves a patriotic family. Almost all of us have served in the IDF, and some of us are career

soldiers. When a family member decides not to join the IDF, the family isn’t happy.” Other

Bedouins who have served in the IDF have now achieved prominent positions within the State

of Israel.[ 12]

“Ismail Khaldi, who started out his career in the IDF, the Israeli

Police, and at the Israeli Defense Ministry, is now working for the Israeli Foreign Ministry

in London. Previously, he was Israel’s Deputy Consul General in the Pacific Northwest region

of the United States. Aetef Karinaoui, a Bedouin Israeli Knesset candidate who has been

politically active, also served proudly in the IDF and runs an organization called Social

Equality and National Service in the Arab Sector, which seeks to encourage all Israeli Arabs

to serve the State of Israel.” (Ref. 12)

As citizens, Bedouins are eligible for benefits from Israel’s

quasi-welfare state. In Rahat, 79% of its residents receive welfare payments, mostly unemployment

benefits. Israel encourages large families and awards an allowance for every child born to an

Israeli citizen. These grants are very common in Rahat, where 65% of the population is under 18.

Meanwhile, hundreds of Israeli citizens are active “in many non-governmental groups that work

to ensure that the challenges of the Bedouin do not go unnoticed. They’re Arabs and Jews,

dedicated to creating a better future for their fellow Israeli citizens.”

(Ref. 13)

“They {Bedouins serving in the IDF} spend their waking hours on the

front line, protecting sovereign Israel and West Bank settlements from terrorist infiltrators.

And then some go home to unrecognized villages, slated for destruction.”

(Ref. 14) Such is part of the dilemma facing

Israel’s Bedouin community.

Life in Israel for Arabs is not all roses. Still, life in the adjoining

Arab countries is far less appealing to most Israeli Arabs and to many Bedouin Muslims. They are

all free to leave Israel – few, if any, do. That says it all!

Israeli-Circassians

Among the nations of the Mid-East, there are none, save the State of Israel,

that have welcomed multitudes of people of diverse cultures, ethnicity and religion to live in their

midst with complete freedom. Israel was born as a sanctuary for a people banished from their

homeland, harassed in exile and ultimately subjected to mass murder. Other peoples that have

undergone similar traumas have found a welcoming home in the Jewish state.

One of the minorities that has found a welcoming environment in the Holy

Land after being persecuted elsewhere is Israel’s small Muslim community of Circassians.

“Some 1.5 million Circassians were killed in the Caucasian War of the mid-to-late 19th century,

and another million — fully 90% of the population — were deported from their land in the

Caucasus Mountains. Today, roughly 4,000 Circassians live in Israel, where they constitute

the country’s only Sunni Muslim community that sends each of its sons {into Israel’s military}.

- - -

“Most Circassians took refuge in the lands of the Ottoman Empire. Today,

2 million of the world’s 7 million Circassians live in Turkey, with another 120,000 in Syria and

100,000 in Jordan. Circassians were Christian for 1,000 years, but from the 16th to the 19th

century became Islamized under the influence of Crimean Tatars and Ottoman Turks.

“In Israel, the community is spread across two villages in the green

hills of the Galilee: Kfar Kama — 13 miles southwest of Tiberias, population 3,000; and Rehaniya —

nine miles north of Safed, population 1,000. In the 16th century, the Circassians also founded

Abu Ghosh, now a famous restaurant town located west of Jerusalem, but their progeny long ago

adopted the Arabic language and culture of their surroundings.

“In 2009, Circassians and Druze . . . staged a joint month-long protest

against what they described as government discrimination, alleging that the two communities received

less state funding than their Arab or Ultra-Orthodox counterparts. After protracted negotiations,

the government last year {2011} allotted $170 million to shore up education, employment, housing

and tourism for both populations.

“The modern histories of Jews and Circassians in the Holy Land are

intimately intertwined. Circassians first settled in Kfar Kama in 1876, Rehaniya in 1878. Four

years later (and just 10 miles away), Zionist immigrants established Rosh Pina, the first Jewish

agricultural settlement in the Galilee.

“Circassians helped Jewish immigrants — many of them illegal — reach the

Promised Land. ‘There was no Ministry of Immigrant Absorption back then. It was the Circassians

who took in those immigrants’ . . .

“’The major division in the Galilee at the time wasn’t between Arabs

and Jews, but between sedentary people and Bedouin nomads. The nomads demanded protection money

from all the sedentary communities . . . The Circassians, who were sedentary and themselves had

come from outside, easily made ties with the Jewish settlers. Later, when the national conflict

between Jews and Arabs began in the British Mandate period, the Circassians generally took neutral

or pro-Jewish stances.

“The Circassians identified with the Jews’ history of exile and dispersion,

and cordial relations were also aided by the fact that many Jews and Circassians understood Russian.

“Israel’s Circassians generally no longer speak Russian, but they continue

to be remarkable polyglots: Most of their children are fluent in Hebrew and Arabic, learn English

at school and their Circassian mother tongue at home. The language (also known as Adyghe)

is written in Cyrillic script and is one of the world’s oldest and most difficult to learn.

“Circassians have a reputation as a warrior people who, until succumbing

to imperial Russia, had defended their strategically located homeland against invaders from

Persians to Huns and Mongols. In the decades after Israel’s creation, male members of the

community flocked to the defense establishment, particularly the border police. - - -

- - -

“- - - in recent years the community has been making its mark far beyond the

defense arena. Today 80% of Circassian youth complete a postsecondary degree. Circassians are even

making waves in international soccer: Kfar Kama’s Bibras Natcho is a midfielder on Israel’s national

team. After four seasons with Hapoel Tel Aviv, he now plies his trade for Russia’s Rubin Kazan team.

“Five years ago, Druze and Circassian authorities launched an ongoing

marketing initiative to encourage Israelis to visit {their} communities’ bed-and-breakfasts, tour

{their} landscapes and enjoy {their} culture.

“The Circassians have prospered in the Jewish state. Still, for many, their

first loyalty remains to their scattered, beleaguered nation, and some espouse an ideology that

Israelis will find familiar: the aspiration for a national home in the land from which they were

forcibly banished. (Ref. 15)

The Circassians in Israel refers to the Adyghe community who live there.

They tend to put an emphasis on the separation between their religion and their nationality. As

is the case with the Israeli Druze living in the state of Israel, since 1958 all male Circassians

(at their leader's request) must complete the Israeli mandatory military service upon reaching

the age of majority, while females do not. Many Circassians in Israel are employed in the Israeli

security forces, including in the Israeli Border Police, the Israeli Defense Forces, the Israeli

Police and the Israeli Prison Service. The percentage of the army recruits among the Circassian

community in Israel is particularly high.[16]

The larger Circassian village of Kfar-Kama has Jewish settlements

as neighbors. Children graduating from the village school continue their education at nearby

Jewish schools. In the village school, the children are taught Hebrew, English and Circassian.

The National Circassian Alphabet of Caucasus is used in teaching Circassian. Reyhaniye is closer

to Arab settlements and children from this village are able to go to both Arab and Jewish schools.

The Circassians living in these two villages communicate in their own Circassian language.

Security, municipal and public service positions are wide open to the

Circassians.[17]

“The Circassian Law (Khabza) regulates the conduct of the Circassians

and {they settle} all matters among themselves.”

(Ref. 17)

The Baha’i

“The Baha'i faith was founded in Iran in 1863 by Mirza Husayn

ali Nuri (1817-92), known as Bahaullah or Baha Allah (Arabic for ‘splendor of God’). This

religion's name comes from the Arabic word for splendor.

“Baha Allah was imprisoned or exiled from 1852 to 1877. During that

time he wrote the Kitab al-aqdas (Arabic for ‘The Most Holy Book’). After his death, his son,

Abbas Effendi (1844-1921) or Abd al-Baha, was named the leader of the community and given the

power to interpret his father's work. At the time of his father's death, the Baha'i were based

in Iran and Acre in Palestine. Through Effendi's travels, he spread the faith around the world.

“Since 1962, the Baha'i have been administered by the Universal House

of Justice, which is elected every five years, and based in Haifa. . . . While their world

headquarters is based in Israel, few Baha'is live there. In Iran, the Baha'is were the

country's largest minority population and were treated with relative tolerance by the

Shah's regime. Since the revolution, however, the Islamic government has persecuted them.

- - -

“The gold-domed Shrine of the Bab in Haifa was built in 1953 to contain

the tomb of Siyyad Ali Muhammed – the Bab – a Muslim in Persia who proclaimed the coming of a

‘Promised One’ in 1844. He was executed in 1850 in Tabriz, Iran, at the age of 31 for heresy.

His disciples who consider him to be a Martyr brought his remains to Haifa in 1909. The man the

Bahais believe was the ‘Promised One’ – Baha Allah – is buried near Akko (Acre) where he died

in 1892.”(Ref. 18)

“The establishment of a Baha'i Department under the Ministry of

Religious Affairs, the official acceptance of Baha'i marriage and the excusing of Baha'i

children from school attendance on Baha'i Holy Days, the exemption of Baha'i properties from

taxation and customs duties are all evidences of the official recognition accorded by the

State of Israel to the World Centre of the Baha'i Faith.”

(Ref. 19)

There is a long-standing arrangement/agreement between the Baha'i

World Center and the Israeli Government that no active teaching of the Faith will occur in

Israel. They have agreed to not proselytize or to try to solicit conversions in Israel.

Baha'u'llah himself instituted this policy more than 50 years before the establishment

of the State of Israel.

Two of the Baha'i's most important shrines are located in Israel:

the Bahai Gardens in Akko (Acre) and the Baha'i Gardens in Haifa, which is comprised of 19

terraced gardens, leading up the slope of Mt. Carmel. This dramatic pathway leads visitors

to the shrine, the highlight of which is the striking gold dome which can be seen for miles.

Inside the shrine, prayer and meditation are encouraged, though no formal prayer service is

held there.

“The Shrine of the Bab {in Haifa} is one of the most recognized

and visited landmarks in Israel. The peaceful gardens and impressive shrine bring in many

pilgrims every year, as well as tourists of all faiths. Despite the importance of these

Israeli landmarks in the Baha'i faith, there is no Baha'i community in Israel. The only

Baha'i residents of Israel are the volunteer workers at the sites. Bahaullah left

explicit instructions that spreading the faith and accepting converts was forbidden in a

land where such preaching might be controversial. The absence of proselytizing, the

tremendous income generated by the holy shrines, and the Baha'i edict of loyalty to

whatever government is in power in their land have forged a very positive relationship

between the Baha'i faith and the Israeli government.”

(Ref. 20)

”Illegals”

Drive along one of the main streets in Tel Aviv early on a week-day morning,

and you will see groups of Blacks standing or sitting on the sidewalks. These are Black refugees

from Africa, mainly Sudan or Eritrea, who have entered Israel illegally. They are sometimes

referred to as “illegals” by Israelis. They are hoping to be picked up by Israeli

contractors and given work.

The illegal arrival of a large number of “undocumented workers from Africa”

into Israel began around 2010, mainly through the unfenced border between Israel and Egypt.

According to the data of the Israeli Interior Ministry, the number of these illegal immigrants

amounted to 26,635 people up to July 2010, and over 55,000 in January

2012.[21]

Many of the undocumented workers are seeking asylum status under

United Nations conventions. But only a fraction of all the undocumented workers are actually

eligible for this status. Many of them, mostly citizens of Eritrea and Sudan, cannot be forcibly

deported from Israel for fear of being killed. The Eritrea citizens (who, since 2009, form the

majority of the undocumented workers in Israel) cannot be deported because they face death,

persecution or enslavement if returned to Eritrea. They have therefore been defined as a "temporary

humanitarian protection group". Despite the fact that a similar opinion does not exist in

relation to citizens of Sudan, Israel does not deport them back to Egypt because of an all-too-real

fear for their fate. Although the immigrants entered Israel from Egypt, Israel cannot deport them

back to Egypt because the Egyptians refuse to promise that they will not deport the immigrants

back to their countries of origin, where their fate would be, at best, uncertain. Accordingly,

the Israeli authorities grant a temporary residence permit to the undocumented workers. Various

authorities in Israel estimate that between 80–90 percent of the undocumented workers live

primarily in two centers: Tel Aviv (more than 60% of the Illegal immigrants) and Eilat (more

than 20%), with a few in Ashdod, Jerusalem and

Arad.[21]

Illegal immigration from Africa to Israel until recently has been relatively

easy because Israel's land border with Egypt has been absent of obstacles. This has changed since 2013

when a fence was erected along the Israel-Egypt border in an effort to stop or slow down the flood of

illegal immigrants. “While 9,570 citizens of various African countries entered Israel illegally in the

first half of 2012, only 34 did the same in the first six months of 2013, after construction of the

barrier was completed. It represents a decrease of over 99%.”

(Ref. 21)

In some of the illegal immigrants' countries of origin humanitarian crises

exist. The UNHCR (United Nations High Commission for Refugees) has declared Eritrea as a country in

humanitarian crisis. In the Darfur region in western Sudan, a genocide has been taking place since

2003. As a result, many of its residents became refugees and fled to Egypt. Added to those were

refugees from southern Sudan, where civil war took place between the predominantly Arab Muslim

inhabitants of the north and the non-Arab, Christian and animist inhabitants of the

south.[21]

Upon their arrival in Israel, most illegal immigrants request

refugee status. Israel does not review the status of the individual asylum seekers from

Eritrea or Sudan, who constitute about 83% of the total coming through the Egyptian border and,

instead, automatically grants them a "temporary protection group" status. This allows these

illegal immigrants to gain a temporary residence permit within Israel. This also means that

they are eligible for a work permit in Israel. In the past, Israel also granted automatic

"temporary protection group" status to all citizens of the Ivory Coast and South Sudan.

After 2005, as conditions in Africa worsened, there was a significant

increase in the number of undocumented workers who crossed the Egyptian border. The numbers of

undocumented workers detained was about 1,000 in 2006. In the first half of 2010, the illegal

immigration rate had increased to over 8,000 in just the first 7 months. The total number of

undocumented workers is clearly greater than these figures, because many were not apprehended.

The early wave of undocumented workers came mainly from Sudan, while in 2009 the majority of

the immigrants were from Eritrea. In early May 2010, it was estimated that over 24,000

undocumented workers resided in Israel.[21]

African illegal immigrants into Israel usually initially arrive in Egypt

from their country of origin by air. From there, they often pay sums of up to $2,000 for Bedouin

smugglers to transfer them to the border between Egypt and Israel. There have been cases of abuse

against the female illegal immigrants committed by the Bedouin smugglers, including rape and other

degradations. Another danger lurking for the illegal immigrants is the Egyptian army policy to

shoot at them in order to prevent their crossing the Egypt/Israel

border.[21]

Here’s an anecdotal story about Israel’s treatment of its Illegals. I recently had

lunch with a former New Englander who now lives in Tel Aviv 6 months out of the year. Her apartment came

with a garage, but she didn’t use it initially since she had no car in Israel. Recently, she bought a car.

When she went to use her garage, she found a car parked at its entrance. Each time she went to get her car

into the garage, there was always a car blocking the entrance – usually a different car each time. She

complained to the police to no avail. She finally found out the reason for her inability to gain entrance

to her garage when she asked one of her apartment neighbors what was going on.

The neighbor explained that there were illegals living in the garage. The people

in her apartment building were deliberately parking at the entrance to the garage to prevent her from using

the garage in order to protect the illegals. In addition, the neighbors were supplying food and other

necessities to the illegals living there.

In Israel, being a survivor and an escapee from genocide has historical

significance and meaning. There are Biblical injunctions to the Israelites to be kind to the

stranger and the needy: “And a stranger shalt thou not wrong, neither shalt thou oppress him;

for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt.” [Exodus XXII, 20].

“And thou shalt remember that thou wast a servant in the Land of

Egypt. ”[Deuteronomy

V, 15]. “For the poor shall never cease out of the land; therefore I command thee,

saying: ‘Thou shalt surely open thy hand unto the poor and needy . . .’” [Deuteronomy

XV, 11]. Israel’s government will not return these survivors of African terror to

their homeland where enslavement or death awaits them and private citizens in Israel are going out of their

way to help these people.

Here's another anecdotal instance of how Israel treats escapees from terror.

In the late 1970s, the North Vietnamese defeated the South Vietnam regime. In the aftermath of the

Vietnam War and the fall of Saigon, hundreds of thousands became refugees. An estimated one million

people were imprisoned and masses were sent to “re-education camps”, where 165,000 people are

reported to have died.

Some 145,000 South Vietnamese were brought to the United States.

For the rest – hoping to escape Communist persecution and torture – there was no choice but to

attempt escape by sea in creaky, overloaded wooden boats.

On June 10, 1977, an Israeli freighter, en route to Taiwan, sighted a

South Vietnamese fishing boat crammed with 66 refugees and took the refugees aboard. No country

was willing to accept these refugees.

But, Menachem Begin’s first act as Israel's new prime minister was to

offer asylum and resettlement to the 66 Vietnamese. Those rescued became the first of three groups

of Vietnamese refugees to be resettled in Israel. From 1977-79, Israel welcomed over 300

Vietnamese refugees. Many of these immigants have remained in Israel to form the core of a thriving Vietnamese

community in Israel.

A few years ago, I met one of these Vietnamese "Boat People" who

was working in a book shop in Jeruslem. When asked how she came to be in Israel, she told the

story of the "Boat People" and their rescue and settlement in Israel. She expressed her gratitude

to the State of Israel for rescuing her and the other escapees from Viet Nam and told me

that she was proud to be a citizen of Israel that had the compassion to take her in, when so many

other countries had turned the refugees away.

.

Jewish Israelis

The Shephardim and the Ashkenazi

Ashkenazic and Sephardic Jews represent two distinct subcultures of Judaism.

“Ashkenazic Jews are the Jews of France, Germany, and Eastern Europe

and their descendants. The adjective ‘Ashkenazic’ and corresponding nouns, Ashkenazi (singular)

and Ashkenazim (plural) are derived from the Hebrew word ‘Ashkenaz,’ which is used to refer to Germany.

“Sephardic Jews are the Jews of Spain, Portugal, North Africa and the

Middle East and their descendants. The adjective ‘Sephardic’ and corresponding nouns

Sephardi (singular) and Sephardim (plural) are derived from the Hebrew word ‘Sepharad,’ which

refers to Spain.”

“Sephardic Jews are often subdivided into Sephardim, from Spain and Portugal,

and Mizrachim, from . . . Northern Africa and the Middle East. The word ‘Mizrachi’ comes

from the Hebrew word for Eastern. . . . Until the 1400s, the Iberian Peninsula, North Africa and the

Middle East were all controlled by Muslims, who generally allowed Jews to move freely throughout the

region. It was under this relatively benevolent rule that Sephardic Judaism developed. When the Jews

were expelled from Spain in 1492, many of them were absorbed into existing Mizrachi communities in

Northern Africa and the Middle East.

“In Israel, a little more than half of all Jews are Mizrachim, descended from

Jews who have been in the land since ancient times or who were forced out of Arab countries after

Israel was founded. Most of the rest are Ashkenazic, descended from Jews who came to the Holy Land

(then controlled by the Ottoman Turks) . . . in the late 1800s, or from Holocaust survivors, or

from other immigrants who came at various times.”

(Ref. 22)

The Yiddish language, which many people think of as the

international language of Judaism, is really the language of Ashkenazic Jews. Sephardic Jews

have their own international language: Ladino, which was based on Spanish and Hebrew

in the same way that Yiddish was based on German and

Hebrew.[22]

“A central tenet of Zionism is that Jews share a common heritage and

destiny. Nevertheless, the reality of Jewish society in the state of Israel is marked by four

prominent social and geo-cultural divisions: Orthodox observant vs. secular, veteran settlers

vs. new immigrants, the haves vs. the have-nots and Geo-cultural origin (European vs. Middle

Eastern or Oriental). - - -

“Left wing critics of Israel, including some within Israel itself and

the Jewish community in America have tended to use the experience and vocabulary of the American

civil rights struggle in order to paint Israel as a racist country. Their central thesis is that

the Oriental Jews . . . have been discriminated against and that this has been a conscious act to

perpetuate ‘white’ European (Ashkenazi) domination. Their contention is that the darker skinned

Sephardim share a common cultural identity and fate with the Palestinian Arabs.

“While it is true that there has been and still is discrimination, and

social snobbery on many levels, the conclusion is wrong, misleading and increasingly less true of

the younger generation. - - -

“Although a gross simplification, it has become acceptable parlance to

divide all Jews into two major geo-cultural groups; ‘Ashkenazim’ . . . and ‘Sephardim’. - - -

- - -

“- - - Israel’s Jews of Afro-Asian origin have shifted from Sephardi

{originally referring to Jews expelled from Spain in1492} to Mizrachi (Oriental). {For simplicity,

I have lumped Mizrachi and Sepaharic Jews together and refer to them as Sephardic Jews.}

- - -

“There is indeed a serious social and geo-cultural cleavage in Israel’s

diverse Jewish population groups, precisely because all the four divisions overlap to a considerable

degree. Most of the Jews from Africa and Asia arrived in Israel after 1948 and, being relative

newcomers, had to adjust to difficult conditions. Most of them arrived destitute and unlike many of

the Ashkenazim never received any reparations for their confiscated property. They still tend to

have larger families and as a rule are much more religiously observant than the Ashkenazim who

established the secular norms and institutions of the Zionist movement and later of the State of Israel.

It is only human nature that the new arrivals from Asia and Africa resented the more established veteran

European settlers and those new immigrants from Europe who immediately found more personal connections

and sympathy with the veteran Ashkenazi settlers through a common knowledge of Yiddish and shared

political and social backgrounds.

“For {all Jews, with the possible exception of the fanatic Haredi

Ultra-Orthodox,} who live in Israel, there is . . . a shared dynamic sense of modern nationhood

that has been instilled by the rebirth of a common Hebrew language, a strong belief in the return

to their historic homeland and the constant threats of a hostile environment. Their unity and

belonging far exceeds that of the incoherent and fractured ‘Arabs’ whose 26 different states and

sheikhdoms have conspired against each other since their achievement of independence from the

Ottoman Empire and the European colonial powers. It also exceeds that of the so called Palestinians,

divided into warring armed factions in the ‘West Bank’ and Gaza Strip and incoherent as to how to

ultimately relate to the Kingdom of Jordan, 70% of whose population regards itself as descendants

of the Palestinian Arab population of Mandatory Palestine.

- - -

“Israel resembles other countries that have been characterized by mass

immigration by people from diverse ethnic backgrounds. There are still tensions and feelings of

deprivation by those who are lowest on the totem pole and, as in the United States, the ‘ethnic’

(or ‘racial’ card) is played by many who seek to appear before the power brokers as self-appointed

‘leaders’ of their ‘community’.

- - -

“Despite the attempts of many Oriental Jews to become fully integrated

into the greater Ashkenazi community in Israel, they were faced with overt discrimination because

their Eastern (Asian or African) society and culture were regarded as ‘Levantine’ (synonymous with

corrupt and backward). Israeli political figures including Ben-Gurion occasionally spoke

disparagingly of the ‘dissident’ underground movements, the Irgun and Stern Gang, and characterized

many of their supporters as ‘primitive Yemenites’ and later used similar language (in private)

in referring to the new immigrants from the Arab countries stigmatizing them as backward and

creating a repressed resentment that endured for decades.

- - -

“{Early on,} the dominant approach of the {Israeli} establishment was

to force the new immigrants into a melting-pot. The new Oriental immigrants in large numbers, in

spite of a predominantly urban pattern of settlement in their original homelands, were shunted into

agriculture in more than 200 moshavim (agricultural cooperatives) or resettled in new

small size development towns in the peripheral Negev, Jerusalem corridor and Galilee and exposed

to constant attacks by Arab ‘fedayeen’ (Arab irregular forces committed to terrorizing the

border population).

“- - - By the 1970s, {the Askenazi attitudes toward the Sephardim} and

the very apparent lower class status of the Mizrachim provoked a new generation to rebel and

assert their own identity as no less authentically Jewish {than the} the older more established

and largely non-observant European derived elite.”

(Ref. 3)

Sephardim have gained political power through their support of the major

rightwing/nationalist party, the Likud, and the largest religious party, Shas.

The success of both parties stems, in disproportionate measure, from the Mizrachim, especially

those who were less well off, and lived in the peripheral regions of the Negev and

Galilee.[3] Much of the division among ethnic

divisions of Israeli society dissolved in the traumatic attack on Israel by massed Egyptian

and Syrian troops in the Yom Kippur war of October 1973, which led to an unprecedented solidarity

among Israelis of all origins whose patriotism outweighed past grievances.

“The real breakthrough in achieving a large measure of Jewish solidarity

in Israel across ‘ethnic’ or geo-cultural lines came about as a result of Mizrachi participation

in the astounding victory of the 1967 Six day War and the long ‘War of Attrition’ followed by the

month long heroic struggle to defeat the Egyptian, Syrian, Egyptian and Iraqi forces in the

Yom Kippur War after the initial surprise attack in October 1973. In 1948, the Mizrachi-Sephardi

component at the time of Israel’s independence was no more than 15% and in 1956, many of the new

immigrants from Asia and Africa were still in temporary transit camps and not fully integrated

into Israeli society or the armed forces. In the military campaigns of 1967-73, a blood covenant

was established that erased much of the negative preconceptions held by many Ashkenazim.

“The Oriental Jews fought on all fronts with distinction and a return

to the old paternalistic attitude of many Ashkenazi politicians was unthinkable. By no means

did much of the still considerable economic, educational and social distinctions between

communities disappear but the result of the war experiences was a watershed after which the

diverse Jewish populations began to assimilate much of what had previously been the hoped-for

Zionist ideals of . . . the Ingathering and Mixing of the Exiles.

“Nevertheless, some Mizrachi intellectuals continue to bear a grudge,

particularly those whose education and economic status is far above the average of their own

community but feel left out, slighted or discriminated against, especially regarding academic

appointments in the limited number of Israeli universities. By all accounts, Israel today is

a much healthier society as regards intra-communal relations and this includes relations with

the newest arrivals of Black Ethiopian Jews. In spite of the constant tensions and threats of

terrorism and war, Israelis have learned to live together and to rely less and less on simply

being tagged with a label whether ethnic, racial or cultural. Much remains to be done and to

find a formula to better integrate approximately a million non-Jews but no other state

in the region has progressed as far and is unique in what it has achieved in enabling people of

so many diverse backgrounds to live and work together. [Emphasis mine]

- - -

“In the important political and military areas, Mizrachim have {now}

reached the highest levels including Commander of the Airforce (Dan Halutz whose parents came

from Iran and Iraq) and Chief of the General Staff (Gabi Ashkenazi despite his name, whose

parents came from Bulgaria and Syria), Defense Ministers Shaul Mofaz (born in Iraq) and Benjamin

Ben-Elizar (also an ‘Iraqi’), Moroccan born Labor Minister Amir Peretz, Moroccan born Foreign

Ministers Sivan Shalom and David Levy (who led the Israeli delegation to the Madrid Conference),

Oxford educated diplomat and historian Shlomo Ben-Ami (a true Sephardi born in Tetuan in the

former Spanish Morocco) and Moshe Katsav (arrived in Israel at age six from Iran) who became

President of Israel.” (Ref. 3)

While the early discrimination against Sephardic Jews by Ashkenazi Jews in

Israel has subsided greatly over the years, a new area of discontent has arisen – that between the

Sephardic community and the Ultra-Orthodox Haredim.

In June of 2010, the Ultra-Orthodox community protested the sentencing of

parents who refused a court order to integrate a religious school where Sephardic and Ashkenazi

students were separated. This event is just one more symptom of the deeply complex ethno-religious

relations between European Jews and Middle Eastern Jews in Israel. Middle Eastern Jews have for

many decades lived as stigmatized citizens of Israel - their traditional Arabic culture and the

form of their Jewish religious practices frequently makes them objects of scorn and prejudice.

“Less obvious than the second-class status of Sephardim in Israel has been

the gradual assimilation of Sephardic Jews into the dominant Ashkenazi collective. In spite of the

fact that Sephardim comprise a substantial percentage of the Israeli Jewish population, in

socio-cultural terms they find themselves in a subservient position vis-à-vis the Ashkenazim.

- - -

“It is critical to understand that some Israeli Sephardim have moved

into the Ultra-Orthodox camp. The establishment of the Shas party in the early 1980s cemented

an integration of Sephardi Jewish interests with the more powerful Ashkenazi Haredi Yeshivas.

The bizarre sight of Middle Eastern Jews dressed in the black garb of the Eastern European

tradition was common in public demonstrations of rank and file Shas members.

- - -

The hysterical Ultra-Orthodox reaction {to the court order to integrate

the Ultra-Orthodox Sephardic students with the Ultra-Orthodox Ashkenazi students} ignited the

bitter religious contentiousness that continues to simmer in Israel. Media accounts described

the Ashkenazi parents and their supporters in terms similar to White supremacists in the U.S.

South and compared the court ruling to Brown v. Board of Education.

“This struggle will continue to be played out on the Israeli stage for

some time. Secular and religious factions are frequently at odds with one another, and in the

case of the . . . Yeshiva, the issue involves state funding of religious institutions that

seem to have no respect for the government and its representatives.

- - -