| |

What are rare earth minerals and why are they important?

According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry,

a rare-earth element (REE) or rare-earth metal (REM) is one of a set of seventeen chemical elements

in the periodic table, specifically the fifteen lanthanides, as well as scandium and yttrium.

Scandium and yttrium are considered rare-earth elements because they tend to occur in the same

ore deposits as the lanthanides and exhibit similar chemical properties, but have different

electronic and magnetic properties.

Despite their name, rare-earth elements are – with the exception

of the radioactive promethium – relatively plentiful in the earth's crust, with cerium being the

25th most abundant element, more abundant than copper. However, because of their geochemical

properties, rare-earth elements are typically dispersed and not often found concentrated.

As a result, economically exploitable ore deposits are not common.

The uses, applications, and demand for rare-earth elements has

expanded over the years. Globally, most REEs are used for catalysts and magnets. In the

United States, more than half of REEs are used for catalysts and ceramics. Important uses

of rare-earth elements are in the production of high-performance magnets, alloys, glasses,

and electronics. Two of the REEs are used for petroleum refining and as diesel additives. Neodymium

is important in magnet production. Rare-earth elements in this category are used in the

electric motors of hybrid and electric vehicles, generators in wind turbines, hard disc

drives, portable electronics, microphones, and speakers.

Cesium, Lanthanum and Neodymium are important in alloy making

and in the production of fuel cells and nickel-metal hydride batteries. Cesium, Gallium

and Neodymium are important in electronics and are used in the production of liquid digital

displays (LCD’s), plasma screens, fiber optics, lasers, and in medical

imaging.

“Rare earths refer to 17 minerals with magnetic and conductive

properties that help power most electronic devices. They are vital to the production of

smartphones, tablets and smart speakers.

“They are not actually ‘rare,’ and can be found in other

countries — including the United States. But they're difficult to mine safely.

“About a third of the world's rare earth deposits

are found in China. Yet the country controls more than 90% of production,

[Emphasis mine] according to the US Geological Survey, in part due to its lower labor

costs and less stringent environmental regulations.

“In addition to their use in electronics, rare earths

are vital to many of the major weapons systems that the United States relies on for

national security. [Emphasis mine]

“That includes lasers, radar, sonar, night vision systems,

missile guidance, jet engines and alloys for armored vehicles . . .”

(Ref. 1)

In mid-2020, “China fired a verbal rocket at U.S. arms maker

Lockheed Martin . . . only to unleash a response which threatens its most strategically

important industry, rare earths.

“Because rare-earth elements have essential uses in a range

of civil and military technologies, such as weapons guidance systems, China’s control

of supply is a powerful commercial and diplomatic bargaining chip.

“Earlier threats to cut-off supplies of the elements, especially

the two most important heavy rare earths, neodymium and praseodymium, have caused

short-term disturbances in the market with China eventually backing off in case it

pushed too hard and international customers developed their own supplies.

“A decade ago a dispute with Japan led to a Chinese rare earth

embargo, but it sparked a response in the form of Japanese financial backing for a new

rare earth mine in Australia and an associated processing facility in Malaysia.

“This time around China is using threats of a rare earth embargo

on Lockheed Martin following the U.S. company winning a contract to upgrade batteries of

Patriot air defence missiles in Taiwan.

“Whether China intends to proceed with an embargo is unclear but

the threat itself has sparked a reaction which involves the U.S. Government and several

allies in pushing ahead with plans to develop non-Chinese supplies of rare earths.

“There has also been a significant reaction by investors who have

boosted the share prices of companies in production or planning to develop rare earth mines.

“The most important development after the threat to Lockheed Martin

was a deal between the U.S. Defense Department and an Australian rare earth miner to push ahead,

with a private U.S. partner, in planning the construction of a rare earth separation facility

in Texas.

“That was followed by . . . the Malaysian Government approving a proposed

site for the permanent disposal of rare earth waste, an important step in ensuring the long term

operation of a plant which processes ore mined by Lynas Corporation in Australia.

“In effect, three countries have moved in near-unison to accelerate

the development of a non-Chinese supply of rare earths in the days after Chinese targeted

Lockheed Martin.

“Australian involvement is through mining one of the world’s richest

deposits of rare earths at Mt Weld in Western Australia. Malaysia is the home of first stage

processing of the mildly radioactive ore which is why a permanent waste disposal site is

important, and the U.S. will be the site of a separation plant to convert a cocktail of rare

earth elements into a usable form.

“That final step, which sees Lynas team up with a U.S. partner,

Blue Line Corporation, and the Department of Defense, is the critical step in a multi-layered

process and the one which could be the key in breaking the Chinese stranglehold of advanced

rare earth processing.

“Currently, even the material mined by Lynas in Australia and processed

in Malaysia goes to China for final separation.

“Investors are starting to recognise that this latest dispute between

China and the international community might be the key to breaking the decades-long dominance

of a strategically important industry.” (Ref. 2)

The United States produces minimal rare earth minerals, but,

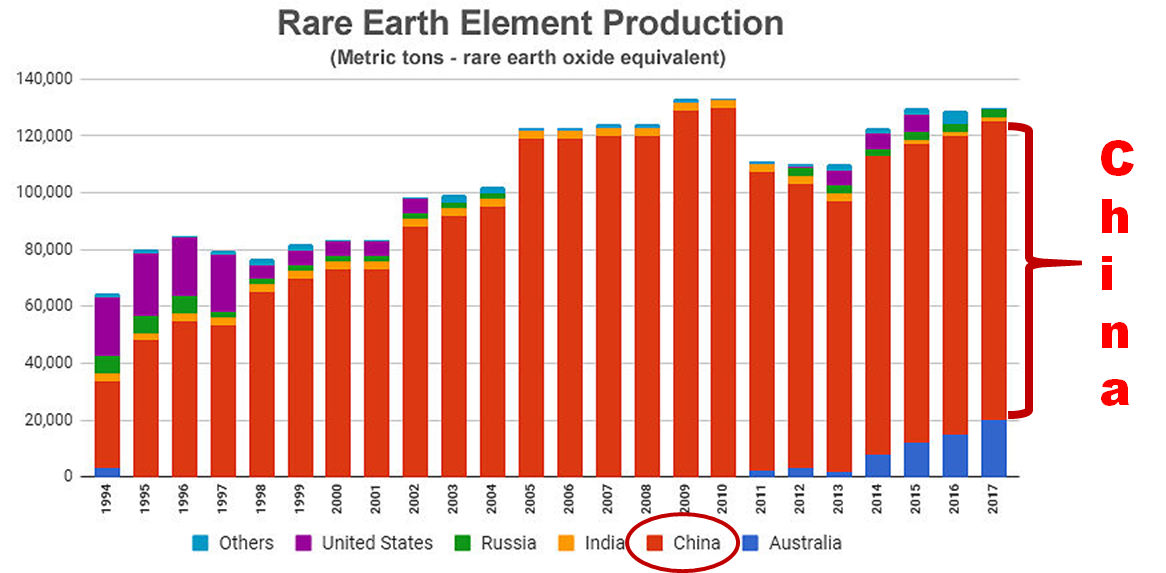

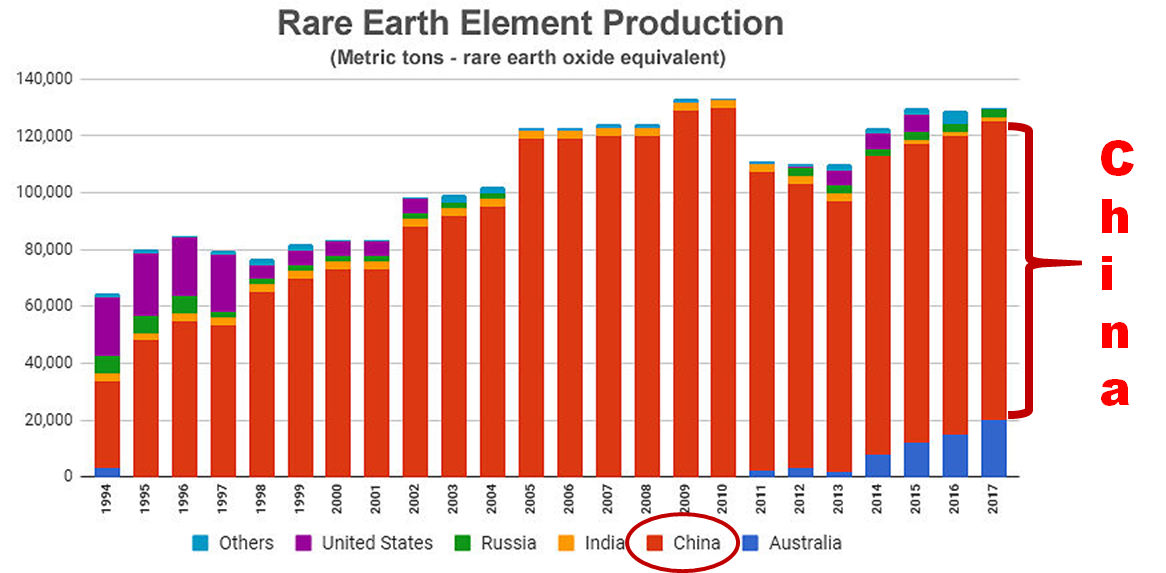

in 2018,China produced more than 70% of the crucial minerals. This is

significant since rare earths are needed for use in most electronic devices, electric vehicles,

wind turbines, and the aerospace and defense industries. They are essential to our modern

society, and the US depends on China’s exports. Globally, rare earth production is

dominated by China.

Here in 2020, The US’ only domestic rare earths producing mine is

California’s Mountain Pass rare earths mine. And for now, it sends its ore to China

to be processed. Mountain Pass says they will kick-start their own processing

operation by the end of 2020. Another two processing operations in the US are expected to

open in mid-2022. Since 1985, China has steadily grown its rare earths production. While

other countries shunned the dirty production of rare earths, China embraced them, realizing

the world’s reliance on rare earths and hence their strategic importance. By the 2000s,

China’s rare earth production dominance grew. Today, China has ~ 40% of the global

rare earth deposits but over 70% of global production!

Between 2006 and 2010, China imposed rare earths quota limits on

production and exports, as they wanted to be sure that they had enough supply for their own

technological and economic needs. The 40% reduction in quotas in 2010 caused a severe rare

earths price spike to start. It also motivated manufacturers to move to China in order to be

sure to meet their needs. In 2010, China and Japan clashed over a territorial dispute in the

East China Sea. As a result, China halted shipments of rare earths to Japan, disrupting the

supply chain for major manufacturers like Toyota and Panasonic. Also in 2010, The U.S.

Department of Energy reported a possible shortage of five rare earth elements. In the same year,

The Rare Earth Supply Technology and Resources Transformation Act was passed in the USA.

The legislation’s goal was: “To provide for the re-establishment of a domestic rare earth

materials production and supply industry in the United States and for other purposes." Between

2010 and 2011, rare earth prices spiked as Chinese export quotas took effect. Prices quadrupled

in 2010, then doubled again in 2011. In 2014 the World Trade Organization (WTO) ruled against

China, which led China to drop the export quotas.

In 2019, there was talk of a possible China retaliation to US tariffs

on Chinese goods and it was reported that China was seriously considering restricting rare earth

exports to the US. The Pentagon sought funds to boost U.S. rare-earth production as fears over

rare earth supplies from China mounted.

Between 2010 and 2019, there were numerous calls for the US to develop

its own rare earths industry, but nothing changed. The Electric Vehicle (EV) boom is expected

to cause a new surge in demand for some rare earths.

While the US lists rare earths as critical materials, we have essentially

done nothing to secure its supply. China still controls the vast majority of the global rare

earth industry and hence controls the supply chain critical to producing high tech electronics,

especially those using magnets. China’s dominance of the sector makes the world very vulnerable

to any Chinese export ban or supply disruption. It makes no sense for the US to be so

reliant on rare earths from China. The US is very vulnerable to a Chinese ban on rare

earths as the US continues to import most of its rare earths from China, either directly or

indirectly as end products such as magnets, electronics, or electric motors. As the era of

electric vehicles takes off demand for rare earths will explode. What will happen if China

refuses to sell rare earths to the US? Thanks to the Rare Earth Supply Technology and Resources

Transformation Act of 2010, the US government did recognize the need to “provide for the

re-establishment of a domestic rare earth materials production and supply industry in the

United States”. But little to no action has been taken to make this happen. U.S. environmental

and permitting rules make it very difficult to start a new rare earths mine in the US today.

With renewed concerns arising as a result of the US-China trade war, we still face the problem

of securing a reliable supply of critical rare earths. Now in mid-2020, the US may have

finally started to take action. Perhaps we have finally come to our senses![3]

In April of 2020, President Donald Trump's administration announced

it would provide a $12 million aid package to Greenland for economic development, raising eyebrows

in Denmark, which has sovereignty over the island. The Trump administration saw this as an

important strategic opportunity. Don’t forget, that in August of 2019, Trump said his

administration was looking into purchasing Greenland. Later, a senior State Department official

said, "There's no plan or interagency process underway involving the purchase of Greenland."

[4]

While President Trump's proposal to buy Greenland lit up social media

feeds and left many scratching their heads, people who work on rare earth materials were not

surprised. Greenland has rare earth supplies. It was feared at the time that the president’s

trade war with China could disrupt access to these metals crucial to green energy, defense

systems and consumer technology.

As with other commodities produced for global consumption in the last

30 years, China’s hinterlands have absorbed a disproportionate share of the pollution generated

by rare earth processing. This also means that scientists in China and their international

colleagues have built unparalleled expertise in how to remediate polluted areas and ensure

that newer facilities do less harm. The problem is that rare earths have been made into a

bargaining chip in the ongoing U.S.-China trade dispute, which overshadows our shared interests

and hobbles our progress toward lasting solutions.

We must capitalize on shared global interests to ensure that the

new rare earth supply chains are the greatest and greenest. This means working with experts

who have already solved technical and environmental problems related to rare earth processing

in other parts of the world, like Japan, the EU, Brazil and China. This is not a radical proposal.

Collaboration among the best minds is the norm for major technological undertakings, including

those considered “critical” or “sensitive” as rare earths currently are.

Although pundits love to conjure a monolithic “China” as the bogeyman

in contemporary rare earth politics, U.S. and Chinese scientists have worked together for decades.

We have much to gain by expanding, rather than suppressing, these means for collaboration.

Focusing on processing rather than mining will actually address the

concerns surrounding China’s dominance in the rare earth sector. The U.S. could open a dozen

rare earth mines and it would do little to change the current situation if we do not invest in

refining rare earths and rebuilding technological manufacturing.

Simply opening new mines means that the refining process and associated

environmental harms remain concentrated in China. Instead, we could create jobs, protect national

security and revitalize U.S. technological leadership by developing a green rare earth refining

and recycling program.

Let’s get out of the 20th-century mentality that mining necessarily

must be dirty and dangerous. There are several promising developments underway to mitigate the

problem, but they need more support. A federal rare earth recycling program could pave the way

for local and private sector initiatives. Currently, less than 1 percent of all rare earths

consumed are recycled. This exacerbates our dependence on China and increases pressure to open

new mines

Laboratory research has revealed possible ways to recover the rare

earth metals from electronic waste. At the Department of Energy’s Ames Laboratory, researchers

have developed an acid-free technique for recovering rare earth metals from shredded hard drives.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania uses ionic ligands to separate two of the rare

earth metals crucial for making powerful magnets.

Opening more mines like it’s 1590 or buying territories like it’s

1867 won’t solve the problem, because the problem is not a shortage of unrefined ores. Instead,

smart R&D investments will bring our production, consumption and disposal practices into the

21st century. This means reducing waste, increasing recycling and repair, and cleaning up the

dirtiest and most dangerous aspects of the supply chain.[5]

In 2019, the U.S. Department of Defense committed funding for two rare

earth separation plants on U.S. soil. This was one small step towards the Trump administration’s

stated goal of breaking the country’s dependence on Chinese supplies of critical minerals. But the

direct involvement of the Pentagon underlines the scale of the task associated with creating from

scratch a non-Chinese rare earths supply chain.

The United States has been almost totally dependent on imports of rare

earth compounds and metals over the last several years China has been the largest supplier to

the tune of around 80% of all imports.

That reliance on China for minerals with critical uses across a wide

spectrum of civilian and military applications is becoming ever more problematic as Sino-U.S.

relations deteriorate.

However, to break it, as the United States is finding out, requires a

mix of direct government support, alliances with like-minded countries, and a long-term focus on

the six-stage process chain from ore to rare earth magnet.

The United States now produces rare earths at the reopened Mountain Pass

mine in California, bought out of bankruptcy in 2017 by MP Materials.

The mine produced 26,000 tons of light rare earth oxide in concentrate

form in 2018, accounting for 12% of global production.

China’s dominance of the first-stage of the global rare earths chain

is weakening, partly due to the return of Mountain Pass and partly due to a displacement of

highly-polluting heavy rare earths mining from China to Myanmar.

However, China’s control of global processing capacity is

almost total, with the exception of Australia’s Lynas Corp which operates a separation

plant in Malaysia.

But, what’s currently mined at Mountain Pass gets

shipped to China to be upgraded into compounds and products which are then shipped back to

the United States.

MP Materials is one of the three companies chosen to receive direct

government funding for a separation plant, while Lynas is teaming up with Texas-based Blue Line

on a heavy rare earths separation plant. The problem, though, is that the oxide generated at both

separation plants may still have to go to China for further processing.

The United States currently has virtually no capacity to

produce neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets, the most common end-use application for rare earths

and one that is set for exponential growth as the global automotive industry migrates to electric

vehicles.

The U.S. is playing catch-up and the Department of Defense’s mandate to

directly invest in separation capacity is a recognition of the nurturing role government will have

to play. The United States is learning that it’s going to need allies if it is to regain some

control of the rare earths sector. The United States has been busy building potential alliances

with both Australia and Canada across a range of critical minerals. It’s also pretty clear that

if the U.S. is it going to fill its domestic magnet-making void it will need Japanese help. Not

only is Hitachi the only non-Chinese player of size, but Japan is further along the path of

cutting rare earth links with China having found itself at the hard end of a Chinese export ban

a decade ago.

It’s taken a decade for Japan to loosen China’s grip on its rare earths

supplies and the United States also faces a long haul. The Department of Defense’s funding for MP

Materials and Lynas/Blue Line is an important step on that road, but it’s set to be a very long

road.[6]

“It happens about once a year . . . in Washington: a think tank or a

group of concerned citizens holds an event centering on the rare earth problem.

“Then a year passes, and another organization puts on a panel discussion

or releases a report where it is revealed that not much has changed over the past 12 months.

“For those unfamiliar with the problem, here is a summary: Rare earths

are a category of strategic minerals that — despite the misnomer — aren’t all that rare. They are

found in abundance here in the United States.

“They are an essential building block in a variety of consumer and

military technologies, including iPhones and Tomahawk missiles.

“The problem is that the United States decades ago abandoned mining and

producing rare earth materials for a variety of reasons.

"Meanwhile, as technology advanced and rare earths became more and

more essential to modern day life,

China stepped into the vacuum and created a monopoly.

“The monopoly extends not only to mining the elements, but more

importantly to refining and processing them into the materials needed for a growing list of

technologies.

“For example, the United States government wants to get away from

China’s dominance in the 5G telecommunications marketplace. It doesn’t trust the main purveyor

of the technology: Huawei. And it’s actively pursuing policies aimed at discouraging U.S.

companies and U.S. allies from depending on China for the next-generation wireless networks.

“Unfortunately, experts say even if U.S. telecom giants were to develop

their own indigenous 5G technology, they would still need to buy tons of processed rare earth

elements from China to make it work.

“So? Start your own mining and processing facility and cash in on the

demand. But be prepared for China to drastically push down the market price for the commodities

in order to aggressively drive competitors out of the business.

“This year’s discussion on rare earths — held virtually due to the

COVID-19 crisis — was organized by the Center for Security Policy, a think tank founded by

former Reagan administration officials.

“Laid bare in the discussion was the usual political split. On the

panel were former Republican Party officials, who wanted the government to help — a little bit,

but not so much that it would make them uncomfortable.

“ ‘We’re good conservatives,’ said . . . a special assistant to the

president for communications under President George H. W. Bush. The government shouldn’t be

picking winners and losers, he said. ‘We don’t want that. We remember the Department of Energy.

We remember the Obama years. We remember Solyndra,’ he said, referencing the DoE program that

loaned millions of dollars to the solar energy company, which ended up filing for bankruptcy.

“ ‘We don’t want to even up the asymmetric contest by nationalizing

U.S. resources,’ . . . If government can signal demand on what’s critical and important it

can help ‘in some small way,’ he said.

“The United States shouldn’t take on China by being more ‘China-like,”

he said. ‘We’re going to lose all the advantage that the U.S. system has.’

“Investment should flow to the best possible candidates with the most

innovative ideas . . .

“The invisible hand of the market and Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations

came up in the discussion.

- - -

“The other side of the coin was {presented by} . . . {the} chief

executive officer of Materia USA, a startup focused on production of critical mineral commodities

from unconventional resources such as recycling.

“There is no U.S. strategy presently available to secure rare

earths, [Emphasis mine] he pointed out. Both Presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump

issued executive orders on strategic minerals, but not much has come of them.

- - -

“{He} saw a bigger role for government. It should breathe life back into

the now nearly defunct and defunded Bureau of Mines.

“ ‘It was the vehicle that kick-started the entire rare earth industry

in this country. That was because it took all of the people who were experts in their field on

the topics of rare earth and project development and procurement, and they basically gave them

the keys to secure the interests for the United States and its national security during the Cold

War.’

“ ‘In order to compete with the Chinese, we are going to have to provide

economic incentives to do so,’ he added.

“While {it was} asserted that ‘the environmentalists and super regulators

want to come in and cripple us and benefit the Chinese,’ {it was} pointed out that some Chinese

communities near these mines have been turned into ecological disaster zones and are nearly

uninhabitable.

“With ‘healthy amounts of regulations, … you can still mine rare earths in

the United States in an economically viable fashion,’ he contended.

“Two different approaches to the problem based on two different political

philosophies is not surprising in Washington.

“But it seems that bold action of some kind is now required on

the part of Congress to jump-start a U.S. rare earths market. Sadly, the words ‘bold action’ and

‘Congress’ are not often spoken in the same sentence nowadays. [Emphasis mine]

(Ref. 7)

In a move to relax its dependency on China for America’s rare earth materials,

a new pilot plant that will process rare earth materials necessary for many critical U.S. military

weapons systems opened in June {2020}, as part of an effort to end China’s monopoly on the important

resources.

The pilot plant is a joint venture between USA Rare Earth and Texas

Mineral Resources Corp. The two companies previously funded a project on Round Top mountain in

Hudspeth County, Texas, which features 16 of the 17 rare earth elements.

The objective was to set up a domestic U.S. supply chain without the

materials ever leaving the United States. The rare earth elements are necessary for a number of

weapons systems including the Lockheed Martin-made F-35 joint strike fighter, Tomahawk cruise

missiles and other munitions.

Once fully commissioned, the plant will be focused initially on group

separation of rare earth elements into heavy, middle and light. The final phase of the pilot will be

the further separation of high-purity individual rare

earth element compounds.

The facility, which is based in Wheat Ridge, Colorado, will also be involved

in the recovery of non-rare earth elements with a focus on lithium, uranium, beryllium, gallium,

zirconium, hafnium and aluminum, all of which are on the U.S. government’s critical minerals

list. [8]

For the past few decades, the United States has allowed itself to become

dependent upon a foreign and potentially hostile nation for materials that are crucial to its

defense needs and which are also essential to domestic technological growth and prosperity. Today,

this situation, long recognized as unacceptable, appears to finally have been given the attention

it has urgently deserved. President Trump’s on-again off-gain trade war with China appears to have

galvanized our government into initiating action to reverse the neglect and inattention to this

issue of such vital economic and security importance. Hopefully, this about face is not too

late.

“Rising tensions with China and the race to repatriate supply chains in

the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic have given fresh impetus to U.S. efforts to launch a renaissance

in rare earths, the critical minerals at the heart of high technology, clean energy, and especially

high-end U.S. defense platforms.

“But it’s not going well, [Emphasis mine] despite a slew

of new bills and government initiatives aimed at rebuilding a soup-to-nuts rare-earth supply chain

in the United States that would, after decades of growing reliance on China and other foreign

suppliers, restore U.S. self-reliance in a vital sector.

- - -

“The problem is that, despite years of steadily increasing efforts

under the Trump administration, the United States—both the public and private sectors—has yet

to figure out how to redress the fundamental vulnerabilities in its critical materials supply

chain, and America still seems years away from developing the full gamut of rare-earth mining,

processing, and refining capabilities it needs if it seeks to wean itself off foreign suppliers.

“This month {May 2020}, Texas Republican Sen. Ted Cruz became the latest

lawmaker to introduce legislation meant to jump-start a domestic rare-earth industry by offering

juicy tax breaks for new projects - and especially large tax incentives for end consumers who

source finished products from American suppliers. Other lawmakers, like Sen. Lisa Murkowski of

Alaska, have pushed legislation of their own meant to spur U.S. development of rare earths.

“The U.S. Defense Department, meanwhile, is trying to throw money at

the problem, putting rare earths at the center of the annual defense acquisition bill three years

in a row, with plans this year to massively increase existing Pentagon funding for rare-earth projects.

All that comes after a drumbeat of Trump administration moves, from a 2017 executive order seeking to

ensure supplies of critical minerals to a 2019 Commerce Department report suggesting ways to do

so.

- - -

“The drive to decouple from China has been thrown into overdrive by

the coronavirus pandemic and new calls from hawks in Washington to take a tougher approach to

confronting Beijing’s rise as a global rival. . .

“. . . lawmakers and Trump administration officials, starting with the

president, are also increasingly leery of maintaining the kind of deep economic integration with

China that has marked the last two decades.” (Ref. 9)

“In May 2014, then-Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin

threatened to cut off the supply of Russian-made RD-180 rocket engines to the United States

as the two great powers tussled diplomatically about the invasion of Ukraine.

“ ‘Wait! What?’ said hundreds of members of Congress. ‘We depend on

Russia for national security launch rocket engines?’

“Most of them didn’t have a clue, but they readily approved funding

for the U.S. industrial base to develop its own rockets, which eventually will mean a loss of

jobs and trade for Russia.

“Five years later, as the United States and China {engaged} in a

bruising trade war, the Association of China Rare Earth Industry — a consortium of six

{Chinese} state-owned companies — said in an Aug. 5 {2019} statement that ‘U.S. consumers

must shoulder the costs from U.S. - imposed tariffs,’ . . .

“And there it is: finally someone in China {was} foolish

enough to pull out the nation’s rare earth monopoly card. Hopefully with this wake-up call,

Congress will make China find out the hard way what Rogozin learned in 2014.”

[Emphasis mine] (Ref. 10)

It’s essential that America takes action to end China’s monopoly

on these critical elements that are necessary for everything from smartphones to critical

weapon systems such as the F-35, along with just about everything Pentagon officials have

called the weapons of the future.

25 years ago, China set out to create a monopoly on rare earth

elements knowing that they would be crucial in the production of modern electronics. Except

for about 10 percent of the world’s supply produced in Japan, it has largely accomplished

that goal. It controls mines and, most importantly, the means of refinement and production.

Back in 1980, the U.S. government in an effort to keep tabs of

thorium - a crucial element in the manufacture of nuclear fuel - passed stringent regulations

on how it should be handled during mining. Heavy rare earths come from thorium-bearing

byproducts. Mining companies decided to bury these byproducts rather than risk liability,

thus inadvertently killing off the U.S. rare earth industry at the dawn of a new technological

age.

America needs to correct this mistake and now, forty years later,

get its head out of the sand and fix the rare

earths problem with the urgency it showed in 2014 with the RD-180 rocket engine.

If we succeed in thwarting

China’s goal of dominating rare earth elements, we will have won an important economic battle

with Beijing that will not only benefit U.S. workers but will also correct a real national security

vulnerability.[10]

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-------------------------

References:

- Rare earths could be the next front in the US-China trade war. Here's what you

should know, Sherisse Pham and Julia Horowitz, CNN BUSINESS,

30 May 2019.

- China’s Rare Earth Threat Sparks An International Backlash, Tim Treadgold,

Forbes, 7 August 2020.

- U.S. finds its Chinese rare earth dependency hard to break, Andy Home,

REUTERS, 28 July 2020.

- After Trump tried to buy Greenland, US gives island $12M for economic developmen,

Conor Finnegan,

abc NEWS, 23 April 2020.

- R&D, not Greenland, can solve our rare earth problem, Julie Michelle Klinger, Ph.D.,

thehill.com,

18 September 2019.

- The U.S. rare earths saga continues…, Matthew Bohlsen,, investorintel,

22 July 2019.

- Bold Action Needed to Solve Rare Earth Problem, Stew Magnuson, NATIONAL

DEFENSE, Page 8,

August 2020.

- Rare Earth Processing Plant Opens in Colorado, Stew Magnuson, NATIONAL

DEFENSE, Page 14,

August 2020.

- U.S. Falters in Bid to Replace Chinese Rare Earths, Keith Johnson and Robbie Gramer,

foreignpolicy.com,

25 May, 2020.

- Make China Pay for Pulling the Rare Earth Card, Stew Magnuson,

NATIONAL DEFENSE, Page 8,

September 2019.

|

|